Thomas J Jordan, Vice Chairman of the Governing Board of the Swiss National Bank, gave a speech at the International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies, Geneva, 17 May 2011 titled Approaching the finishing line – the too big to fail

project in Switzerland

A central component of the Swiss approach is that systemically important banks should markedly improve their capital base and liquidity positions, both qualitatively and quantitatively, and reduce their risk exposure to other banks.(footnote)

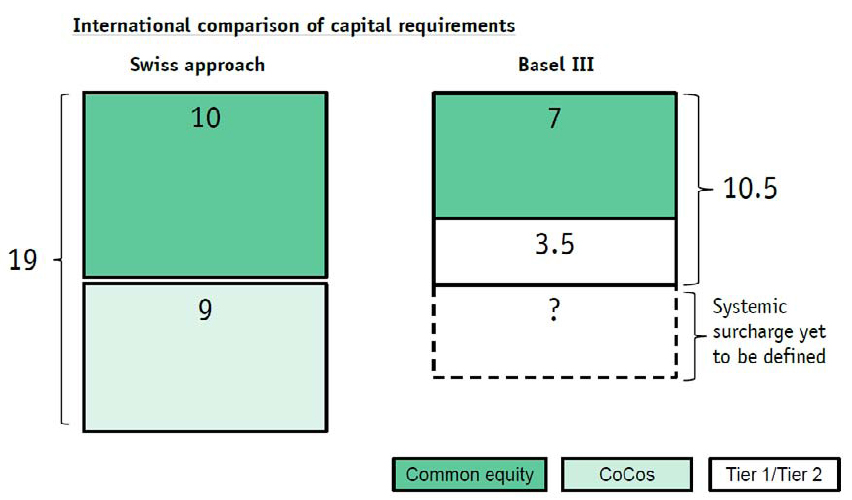

Footnote: The new capital adequacy regulations for systemically important banks are to apply to risk-weighted capital and to the leverage ratio. Furthermore, they are designed to be progressive. In other words, the bigger the bank, the higher the requirement. Given the current size of Switzerland’s two big banks, the requirement would be 19% total capital of the risk-weighted assets, of which 9% can be held in convertible capital (cocos) and 10% must be held in common equity.

I am very pleased to see that the capital adequacy requirements are progressive and that the exposure to other banks is being addressed.

I can’t say I’m similarly impressed by the trigger for the cocos (I would prefer a trigger based on market price of the common)

If common equity falls below the threshold of 5%, the cocos will be converted and the emergency planning for separating the systemically important functions from the rest of the bank will be initiated.

… but you can’t have everything!

He takes a little dig at the US solution of banning prop-trading by the banks:

Firstly, regulation is never free of charge for every participant. However, analysis of the possible costs of regulation must always differentiate between the private and the social costs: in practice, regulation is bound to lead to additional costs for those regulated. This is part of the plan and makes economic sense provided that these additional costs are smaller than the benefits that regulation brings to the entire economy. If regulation leads to the elimination or reduction of market distortions – such as subsidies, for example – then an economically more efficient result is obtained.

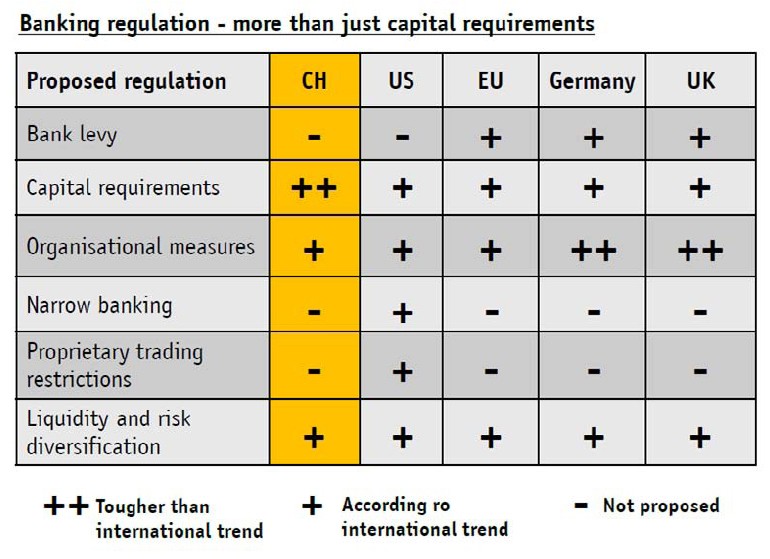

Secondly, regulation can be formulated in a more or less cost-efficient manner. Particular attention was paid to this element in Switzerland. For instance, the additional capital required here by systemically important banks can largely be held in the form of more cost-efficient convertible capital. Other, far more drastic measures, such as a strict ban on certain business activities or the introduction of a bank tax – as discussed in other countries – were firmly rejected, partly for cost reasons.

He then provides an economic rationale for CoCos:

an increase in capital should not have any effect on a bank’s overall financing costs. Owing in part to the preferential tax treatment of borrowed funds, the Modigliani-Miller theorem referred to here, cannot be applied directly in practice, which means that overall financing costs would rise if capital increases. However, this is exactly what the proposed measures on convertible capital take into account. They create better conditions, so that capital structure will have less influence on a bank’s financing costs.

I liked Chart 2:

But Chart 8 was pretty good to:

And there’s a handy scoresheet!