The Bank of Canada has released the Summer 2011 Bank of Canada Review:

This special issue, “Real-Financial Linkages,” examines the Bank’s research using theoretical and empirical models to improve its understanding of the linkages between financial and macroeconomic developments in the wake of the recent global financial crisis.

Very important, I know – and it’s what the Bank’s job is all about! – but not my favourite topic.

Articles are:

- Introducing Multiple Interest rates in ToTEM

- The BoC-GEM-Fin: Banking in the Global Economy

- Bank Balance Sheets, Deleveraging and the Transmission Mechanism

- Mortgage Debt and Procyclicality in the Housing Market

- Developing a Medium-Term Debt-Management Strategy for the Government of Canada

I found the last article, by Marc Larson and Étienne Lessard, to be too general to be satisfying, but there were some interesting points:

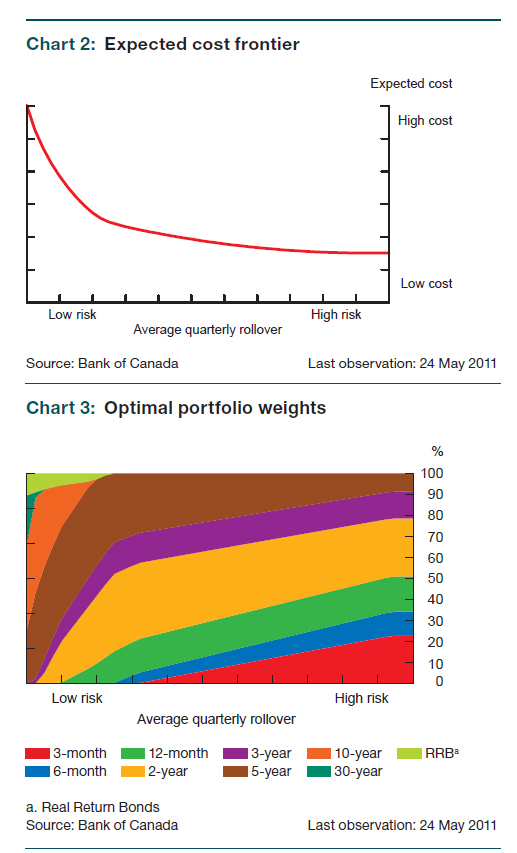

Step 3 – Selecting optimal strategies In this step, a wide range of different financing strategies are reviewed, some of which may involve issuing debt in only some maturity sectors but not others. An optimization algorithm is then used to select those strategies with the best cost-risk tradeoffs, or the lowest cost for a specific level of risk. The output of this work is a curve that represents the most efficient financing strategies, similar to an efficient portfolio frontier, as well as the composition of the most efficient financing strategies.

Chart 2 and Chart 3 illustrate the results of the optimization exercise based on debt rollover as a risk measure. Note that the same exercise can also be performed using other risk measures. Chart 2 shows the efficient frontier of the optimal debt structures (lowest cost for a specific level of risk). Moving along this frontier from left to right shows how expected borrowing costs decrease—and rollover risk increases—as the government shifts the proportion of its borrowing program from long-term debt to shortterm debt. Chart 3 illustrates how the proportion of short-term debt in the optimal portfolio changes as one moves along the efficient frontier. Each colour represents a different debt instrument issued by the Government of Canada. As shown in this chart, low risk debt structures contain mainly long-term maturity instruments (10-year and 30-year nominal bonds and Real Return Bonds), while high-risk debt structures contain mostly short-term debt instruments (3-, 6- and 12-month treasury bills and 2-year bonds).

I find the relationship between efficient amounts – as defined – of long nominals vs. RRBs to be fascinating. I suppose part of the reason for the relationship is that they are considered to have similar cost, but a big chunk of the RRB return is paid only on maturity; therefore they will have a lower quarterly rollover rate (less risk) at the same [relationship of] cost. Maybe! I’d have to look at the model in more detail!

However, rest assured that I will be quoting the bank’s conclusions on risk to support my “security of income” vs “security of principal” argument until you are all heartily sick of it, never fear! The risk of variance of investor’s income is exactly the flip side of the risk of variance of the Bank’s expenses.

The article on bank balance sheets by Césaire Meh uses a model to derive interesting relationships between counter-cyclical capital buffers and monetary policy. Note that “(demand-type) financial shocks … generate simultaneous downward pressures on inflation and credit contractions.” – i.e., a standard recession,while “(supply-type) financial shocks … cause credit contractions and upward inflation pressures,” i.e., a financial crisis / credit crunch:

Overall, these results suggest that the impact of countercyclical capital buffers on the transmission mechanism of monetary policy and, consequently, the nature of the coordination between these two tools, depend on the nature of the shocks experienced by the economy. Demand-type financial shocks pose no inherent trade-offs between stabilizing credit and achieving price stability. In this case, the use of countercyclical capital buffers eases the pressure on monetary policy, and less-aggressive movements in the interest rate would be required to achieve economic stability. Supply-type financial shocks, however, can generate a tension between stabilizing credit and price stability. In this case, activating countercyclical capital buffers could make it harder to stabilize inflation, and more-aggressive movements in the interest rate would be required. Under such circumstances, proper coordination between the two policy instruments will lead to a better policy outcome. [Footnote]

Footnote: Countercyclical capital buffers should be considered neither a substitute for monetary policy nor an all-purpose stabilization instrument. Rather, they should be viewed as a useful complement to monetary policy in a world in which financial shocks have become an important source of economic fluctuations.