The Bank for International Settlements has released a working paper by Mathias Drehmann, Claudio Borio and Kostas Tsatsaronis titled Anchoring countercyclical capital buffers: the role of credit aggregates:

We investigate the performance of different variables as anchors for setting the level of the countercyclical regulatory capital buffer requirements for banks. The gap between the ratio of credit-to-GDP and its long-term backward-looking trend performs best as an indicator for the accumulation of capital as this variable captures the build-up of system-wide vulnerabilities that typically lead to banking crises. Other indicators, such as credit spreads, are better in indicating the release phase as they are contemporaneous signals of banking sector distress that can precede a credit crunch.

They explain:

We find that the variable that performs best as an indicator for the build-up phase is the gap between the ratio of credit-to-GDP and its long-term trend (the credit-to-GDP gap). Across countries and crisis episodes, the variable exhibits very good signalling properties, as rapid credit growth lifts the gap as early as three or four years prior to the crisis, allowing banks to build up capital with sufficient lead time. In addition, the gap typically generates very low “noise”, by not producing many false warning signals that crises are imminent.

The credit-to-GDP gap, however, is not a reliable coincident indicator of systemic stress in the banking sector. In general, a prompt and sizeable release of the buffer is desirable. Banks would then be free to use the capital to absorb writedowns. A gradual release would reduce the buffer’s effectiveness. Aggregate credit often grows even as strains materialise in the banking system. This reflects in part borrowers’ ability to draw on existing credit lines and banks’ reluctance to call loans as they tighten standards on new ones. A fall in GDP can also push the ratio higher. Aggregate credit spreads do a better job in signalling stress. However, their signal is very noisy: all too often they would have called for a release of capital at the wrong time. Moreover, as spread data do not exist for a number of countries their applicability would be highly constrained internationally.

We conclude that it would be difficult for a policy tool to rely on a single indicator as a guide across all cyclical phases. It could be possible to construct rules based on a range of conditioning variables rather than just one, something not analysed in this paper. However, it is hard to envisage how this could be done in a simple, robust and transparent way. More generally, our analysis shows that all indicators provide false signals. Thus, no fully rule-based mechanism is perfect. Some degree of judgement, both for the build-up and particularly for the release phase, would be inevitable when setting countercyclical capital buffers in practice. That said, the analysis of the political economy of how judgement can be incorporated in a way that preserves transparency and accountability of the policymakers in charge goes beyond the scope of this paper.

It’s a lucky thing that judgement is required for the process to work – otherwise there might be layoffs in the regulatory ranks! It’s also a lucky thing that details regarding the incorporation of judgement are beyond the scope of the paper, as otherwise one might have to examine the track record of the regulatory establishment in predicting crises.

I suggest that incorporating the judgement of the regulators into the process will have numerous effects:

- Increasing politicization of the regulatory bureaucracy

- Fewer crises (since the regulators will tend to err on the side of caution)

- More severe crises (since the range of judgments existing in the private sector will be replaced by a one-size-fits-all judgment imposed according to the fad of the day)

- increased uncertainty during a crisis, as both the sellers and the buyers of new bank capital will be unsure as to whether or not the buffers will be released.

I suggest that eventually we will regret the role of regulatory judgement to the extent that it is incorporated into the process.

I believe that the release of countercyclical buffers should be linked to the amount by which a bank’s write-offs have exceeded the norm for the past one (maybe two?) years. This would encourage (or at least mitigate the discouragement) of recognition of losses and provide a time limit for raising replacement capital (since the release will be effective for only one (maybe two) years.

The authors considered using bank losses as the anchor (building-up) indicator:

Aggregate gross losses: This indicator of performance focuses on the cost side (non-performing loans, provisions etc). The financial cycle is frequently signalled by the fall and rise of realised losses.

Although the use of this signal is not supported by the raw data, I suggest that:

- It provides the most logical link to the condition that one is trying to alleviate, and

- the knock-on effect of such a change (i.e., the way in which behaviour will be adjusted to account for the adjustement in rules) is in this case highly desirable – losses will be recognized faster.

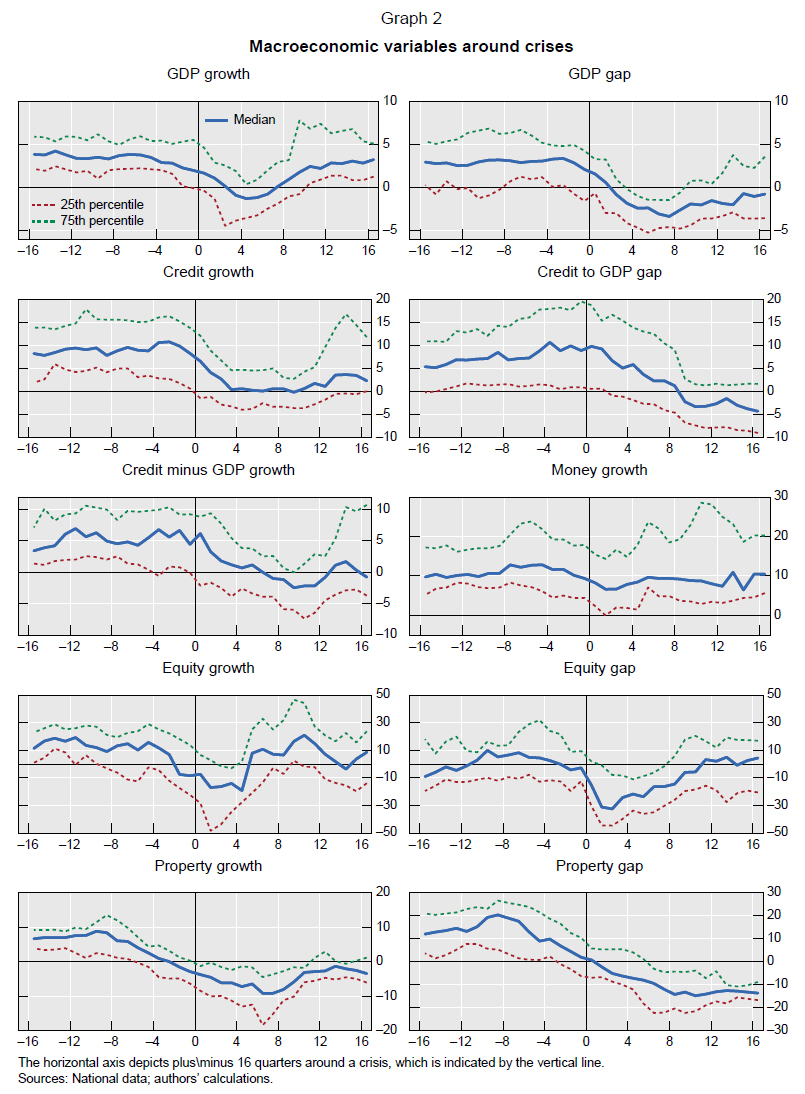

As the authors’ graph shows, there’s no magic formula for predicting a bank crisis:

Although the credit-to-GDP gap is the best-performing indicator for the build-up phase, Graph 2 indicates that it declines only slowly once crises materialise. This is also borne out by the statistical tests shown in Tables 5 to 7. As before, bold values for “Predicted” highlight thresholds for which a release signal is issued correctly for at least 66% of the crises. The bold noise-to-signal ratio indicates the lowest noise-to-signal ratio for all threshold values that satisfy this condition.

None of the macro variables and of the indicators of banking sector conditions satisfy the required degree of predictive power to make them robust anchor variables for the release phase, ie none of these variables signals more than 66% of the crises. The best indicator is a drop of credit growth below 8%. This happens at the onset of more than 40% of crises and such a signal provides very few false alarms (the noise-to-signal ratio is around 10%).

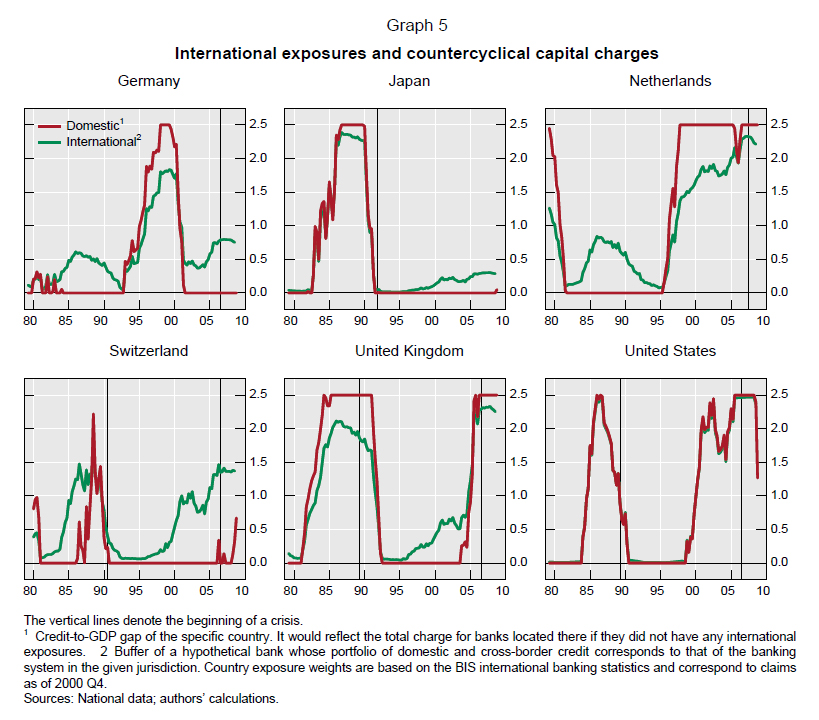

A backtest of the Credit Gap as an anchor variable is encouraging:

Part of the authors’ conclusion is:

The analysis shows that the best variables to signal the pace and size of the build-up of the buffers differ from those that provide the best signals for their release. Credit, measured by the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its trend, emerges as the best variable for the build-up phase, as it has the strongest leading indicator properties for financial system distress. A side-benefit of using this variable as the anchor is that it could help to restrain the credit boom and hence risk taking to some extent.

…

A final word of caution is in order. Are our empirical results subject to the usual Lucas or Goodhart critiques? In other words, if the scheme proved successful, would the leading indicator properties of the credit-to-GDP variable disappear? The answer is “yes”, by definition, if the criterion of success was avoiding major distress among banks. As credit exceeds the critical threshold, banks would build-up buffers to withstand the bust. If, in addition, the scheme acted as a brake on risk-taking during the boom, the bust would be less likely in the first place. However, the answer is less clear if the criterion was the more ambitious one of avoiding disruptive financial busts: busts could occur even if banks remained reasonably resilient. In either situation, however, the loss of predictive content per se would be no reason to abandon the scheme.

One thing I will note is that it may be helpful to disaggregate the accumulation signal. As has previously been reported on PrefBlog, residential real-estate now makes up more than 40% of Canadian banks’ credit portfolios, vs. the more normal 30%. I suggest that it would be useful to examine the components of the credit gap, in the hopes that one or more of them will prove a better signal than the complete set.

It may also be the case that changes in the proportion of various components of aggregate credit are just as important as the aggregate amount itself – these changes could be indicative of dislocations in the economy that will have grievous effects if, as and when they return to normal.

[…] possible downgrade serves as a great argument in favour of countercyclical capital buffers. This is much more general than the micro-management indulged in so far, because, if properly […]