The Bank of Canada has released the June 2009 Financial System Review with the usual high level views of government and corporate finance.

I was most interested to see a policy recommendation in the review of the funding status of pension plans. First they state the problem:

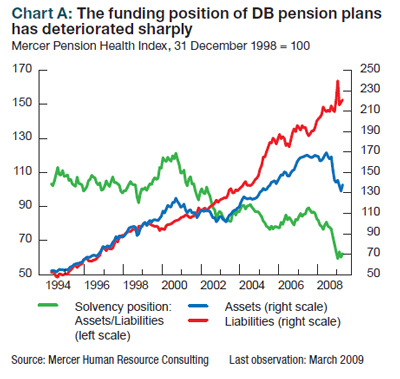

Assets fell in 2008, largely because of the steep decline in Canadian and international equity markets. At the same time, declines in long-term bond yields caused the present value of liabilities to increase.

… and provide an illustration:

… and provide a prescription:

In this environment, plan members are concerned about pension obligations being met.

To address these issues, reforms should focus on: (i) flexibility to manage risks and (ii) proper incentives. Reforms (regulatory, accounting, and legal) should also focus on providing sponsors with the flexibility needed to actively maintain a balance between the future income from the pension fund and the payouts associated with promised benefits. Small pension funds should be encouraged to pool with larger funds to better diversify market risk as another way to help make pension funds more resilient to market volatility.

I may be a little slow, but I fail to follow the chain of logic between the premises and the conclusion that “small pension funds should be encouraged to pool with larger funds to better diversify market risk”.

This will not affect the liability side, which is based on the long Canada rate. But the Bank fails to show – or even to suggest – that the decline in assets was exacerbated by lack of diversification, that large pools are better diversified than small funds, or that pooled funds outperform small funds.

It may well be that these logical steps can be justified – but they ain’t, which makes me suspicious. The recommendation is supportive of the Ontario government’s lunatic plan to encourage the bureaucratization of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP) and OMERS, as discussed on March 31, without either mentioning the proposal or providing any of the supporting arguments that were also missing from the original.

This has the look of a quid pro quo – either institution to institution, or the old regulatory game of setting up some lucrative post-retirement consulting gigs. Even if completely straightforward and honest, the argumentation in this section is so sloppy as to be unworthy of the Bank.

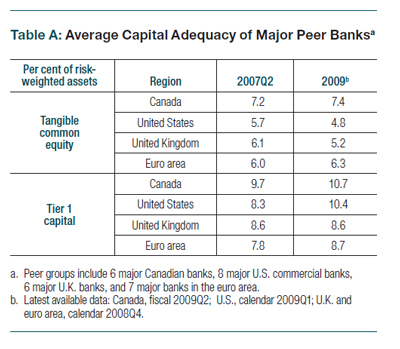

Of more interest to Assiduous Readers will be the section on banks, commencing on page 29 of the PDF.

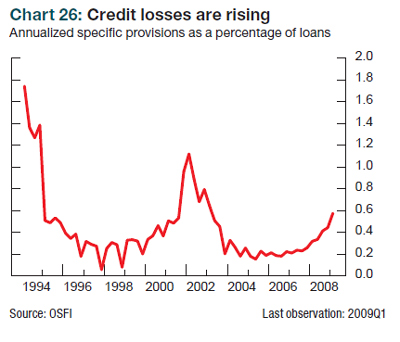

There are two things of interest here: first, for all the gloom and doom, credit losses are not as high as the post-tech-boom slowdown, let alone the recession of 1990; second, that the graph is cut off after the peak of the 1990 recession.

Why was the graph prepared in this manner? Given the Bank’s increased politicization (also evidenced by the pension plan thing) and increased regulatory bickering with OSFI, I regret that I am not only disappointed that they are not encouraging comparison with the last real recession, but suspicious that there is some kind of weird ulterior purpose. Whatever the rationale, this omission reflects poorly on the Bank’s ability to present convincing objective research.

There are a number of longer articles on the general topic of procyclicity:

- Procyclicality and Bank Capital

- Procyclicality and Provisioning: Conceptual Issues, Approaches, and Empirical Evidence

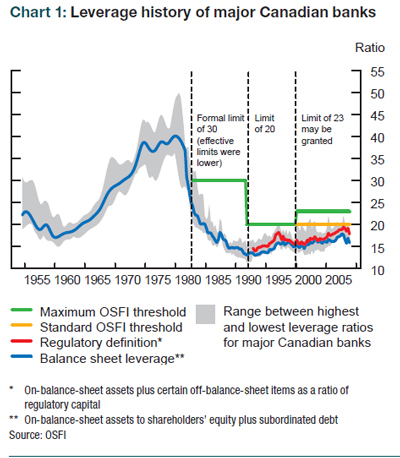

- Regulatory Constraints on Leverage: The Canadian Experience

- Procyclicality and Value at Risk

- Procyclicality and Margin Requirements

- Procyclicality and Compensation

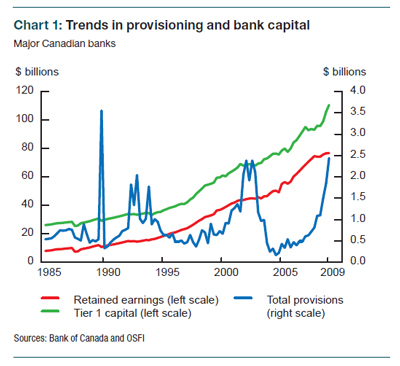

The second article includes a chart on provisioning; not the same thing as credit losses, but a much better effort than that given in the main section of the report:

I was disappointed to see that bank capital and dynamic provisioning were discussed in the contexts of the general macro-economy and with great gobbets of regulatory discretion. I would much prefer to see surcharges on Risk Weighted Assets related to both the gross amount and the trend over time of RWA calculated by individual bank.

The emphasis on regulatory infallibility is particularly distressing because it is regulators who bear responsibility for the current crisis. The banks screwed up, sure. But we expect the banks to screw up, that’s why they’re regulated. And the regulators dropped the ball.

The paper on leverage has an interesting chart:

Update, 2009-7-21:

On DB pensions, there is a nice annual report (http://www.fsco.gov.on.ca/english/pensions/DBFundRep09.pdf) that explains quite a few things, of which the following are relevant:

1. Small funds have higher proportional expenses and often end up in pooled funds with mutual-fund like MER. Hence, it makes sense to consolidate to reduce plan costs and improve long run net returns. I was surprised to see that $100M+ funds had expenses of >>1%.

2. In my view DB pensions are doomed because, egged on by actuaries that don’t know anything about the stock market, pension plans assume long run equity returns of 8%+ (and are typically 60% equity). If you look at where historical returns came from — eg. Robert Shiller data for S&P-500 back to 1870, you find (at constant P/E): long run return = dividend yield plus inflation plus real growth in EPS of the index (1.6%). Given a current US dividend yield of 2.4%, inflation expectations of 2%, one can only expect 6% from equities looking forward. We got more in the past (e.g. 10% since 1980 from P/E expansion (from 7 to 20), higher dividends and higher inflation.

Anyway, the poor pension plans aren’t accumulating enough contributions because the contribution rate is based on the return assumption. Furthermore, now that most funds are vastly underfunded, many companies cannot afford the makeup payments, which can amount to 40% of annual revenue. On top of that, failing to recognize and deal with any of this means that current retirees are pulling out full pensions from chronically underfunded plans — making it harder for working employees to even maintain constant underfundinging. Just look at the GM plan, which is about 50% funded — for nearly two decades.

And, sadly for those who believe the Ontario Pension Benefits Guarantee Fund might help them out, the PBGF has a $100M deficit funded by a “loan” from the government, and doesn’t collect anywhere enough fees from plans (especially the large underfunded ones). It seems GM workers were very lucky to get a $2B pension “loan” directly from the government because none of the rest of us will….the cost to fix Ontario pensions is at least $40B or 40% of the annual budget.

So, the Bank of Canada wants to nibble around the edges of the titanic…

“flexibility” is code for being able to reduce benefits, if needed, which is almost certain.

Hence, it makes sense to consolidate

Via pooled funds?