The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) has released a speech by Julie Dickson to the C.D. Howe Institute titled Considerations along the Path to Financial Regulatory Reform.

The most important part was the section on contingent capital:

Explore the use of contingent capital. This refers to sizeable levels of lower quality capital that could convert into high quality capital at pre-specified points, and clearly before an institution could receive government support. Such conversions could make use of triggers in the terms of a bank’s lower quality capital, while the bank remains a going-concern. This would add market discipline for even the largest banks during good times (as common shareholders could be significantly diluted in an adverse scenario), while stabilizing the situation by recapitalizing such banks if they fall on hard times. Boards and management of these recapitalized banks could be replaced. Issues to be studied to make such a proposal operational include grandfathering of existing lower quality securities, and/or transitioning towards new features in lower quality securities, considering capital markets implications of changing the terms of lower quality capital and the selection of triggers, and determining the amounts and market for such instruments.

Contingent capital was first proposed in such a form – as far as I know! – in HM Treasury’s response to the Turner Report.

Under the heading Making Failure a Viable Option, she advocates:

More control of counterparty risk via capital rules and limits, so that imposing losses on major institutions who are debt holders in a failed financial institution does not prove fatal.

It is possible that this might be an attack on the utterly ridiculous Basel II risk weighting of bank paper according to the credit rating of the bank’s supervisor; that is, paper issued by a US bank is risk-weighted according to the credit rating of the US, which is perhaps the most difficult thing to understand about the Basel Rules. If the regulators are serious about reducing systemic risk, then paper issued by other financial institutions should attract a higher risk weighting than that of a credit-equivalent non-financial firm, not less.

I have often remarked on the Bank of Canada’s attempts to expand its bureaucratic turf throughout the crisis; two can play at that game!

one could try to experiment and adjust capital requirements up or down based on macro indicators. But, the challenge will be how to make a regime which ties macro indicators to capital effective. Indeed, in upturns in the domestic market where capital targets are increased due to macro factors, companies would have the option to obtain loans from banks in countries with less robust economic conditions, as banks in that country will have lower requirements. Thus, an increase in capital in the domestic market might not have the desired impact of slowing things down.

Alternatively, because many countries have well developed financial sectors, borrowers can go beyond the regulated financial sector to find money, as regulated financial institutions are not the only game in town.

Umm … hello? The objective of varying credit requirements is to strengthen the banks should there be a possible downturn; the Greenspan thesis is that it is extremely difficult to tell if you’re in a bubble while you’re in the middle of it (and therefore, you do more damage by prevention than is done by cure) has attracted academic support (as well as being simple common sense; if a bubble was obvious, it wouldn’t exist).

Most authorities agree that Central Banks have the responsibility for “slowing things down” via monetary policy; OSFI should stick to its knitting and concentrate on assuring the relative health of the regulated financial sector it regulates.

Of particular interest is her disagreement with one element of Treasury’s wish-list:

Yes, regulators should try to assess systemic risk. But no, we should not try to define systemically important financial institutions.

…

The IMF work on identifying systemic institutions rightly points out that what is systemic in one situation may not be in another, and that there is considerable judgement involved.

Ms. Dickson also made several remarks about market discipline, which should not be taken seriously.

Update: I’ve been trying to find the “IMF work” referred to in the last quoted paragraph; so far, my best guess is Chapter 3 of the April ’09 Global Financial Stability Report:

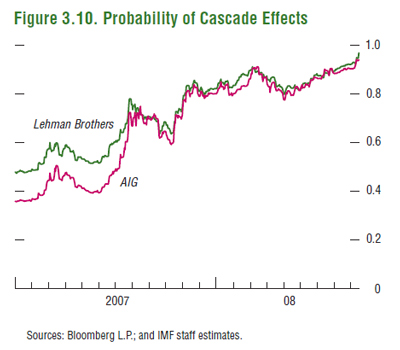

Cascade effects. Another use of the joint probability distribution is the probability of cascade effects, which examines the likelihood that one or more FIs in the system become distressed given that a specific FI becomes distressed. It is a useful indicator to quantify the systemic importance of a specific FI, since it provides a direct measure of its effect on the system as a whole. As an example, the probability of cascade effects is estimated given that Lehman or AIG became distressed. These probabilities reached 97 percent and 95, respectively, on September 12, 2008, signaling a possible “domino” effect in the days after Lehman’s collapse (Figure 3.10). Note that the probability of cascade effects for both institutions had already increased by August 2007, well before Lehman collapsed.

The IMF Country Report No. 09/229 – United States: Selected Issues points out:

It remains to be seen how the Federal Reserve, in consultation with the Treasury, will draw up rules to guide the identification of systemic firms to be brought under its purview, and how the FSOC will ensure that remaining intermediaries are monitored from a broader financial stability perspective. Although the criteria for Tier 1 FHC status appropriately include leverage and interconnectedness as well as size, identifying systemic institutions ex ante will remain a difficult task (cf., AIG).

I have sent an inquiry to OSFI asking for a specific reference.

Update, 2009-11-9: OSFI’s bureaucrats have not seen fit to respond to my query, but the Bank for International Settlements has just published the Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Governors: Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments: Initial Considerations which includes the paragraph:

The assessment is likely to be time-varying depending on the economic environment. Systemic importance will depend significantly on the specifics of the economic environment at the time of assessment. Structural trends and the cyclical factors will influence the outcome of the assessment. For instance, under weak economic conditions there is a higher probability that losses will be correlated and failures in even relatively unimportant elements of the financial sector could become triggers for more general losses of confidence. A loss of confidence is often associated with uncertainty of asset values, and can manifest in a contagious “run” on short-run liabilities of financial institutions, or more generally, in a loss of funding for key components of the system. The dependence of the assessment on the specific economic and financial environment has implications about the frequency with which such assessments should take place, with the need for more frequent assessments to take account of new information when financial systems are under stress or where material changes in the environment or the business and risk profile of the individual component have taken place.

It is regrettable that OSFI does not have a sufficiently scholarly approach to its work to provide references in the published version of Julie Dickson’s speeches – or that she would not insist on such an approach. It is equally regrettable that OSFI is unable to answer a simple question regarding such a reference within a day or so.

[…] OFSI Joins Contingent Capital Bandwagon […]

[…] OSFI Joins Contingent Capital Bandwagon […]

[…] BIS has published the Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Governors: Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments: Initial Considerations, which is the missing reference in Julie Dickson’s recent speech. […]

[…] Ms. Dickson’s opposition to Treasury’s proposal to designate systemically important institutions is well known, but the fact that “coming up with the capital charge would be hugely challenging” is hardly a reason to ignore the issue. […]

[…] and convertible capital instruments could play in the regulatory capital framework.” See also “Considerations along the Path to Financial Regulatory Reform,” remarks by Superintendent Julie Dickson, Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, 28 […]