Revolving door regulation is usually more subtle than this:

Lerner, 60, pleaded guilty this week to public-corruption charges. Commerzbank hired him from the Internal Revenue Service in 2011 while he was an examiner responsible for negotiating a tax-fraud settlement with the bank, according to the criminal complaint that prosecutors filed in September. Commerzbank paid the IRS $210 million one day before offering Lerner the job, which he accepted immediately. The figure was 62 percent of the potential taxes due. Bank employees later told federal investigators it had been willing to pay much more money to settle the audit.

…

The government’s complaint said Lerner met in New York with unidentified Commerzbank executives in July and August 2011 to discuss the IRS’s audit and his possible employment at the bank. After Lerner told the IRS he was resigning in August 2011, his supervisor there gave him a document describing his lifetime prohibition on attempting to influence IRS employees regarding matters he had worked on at the agency. Lerner’s resignation letter didn’t identify Commerzbank as his new employer. Later that month, Lerner participated in a meeting at the IRS about the bank’s settlement, according to the government’s complaint.The $210 million tax settlement Lerner negotiated with Commerzbank was still pending final approval when he left the IRS. After Lerner began working at Commerzbank in September 2011, the government said he spoke repeatedly with IRS examiners involved in the audit, asking about the status of the case and arguing on Commerzbank’s behalf to bring it to a close. Some of the discussions took place with another Commerzbank employee present.

I have previously criticized Modigliani-Miller in the context of bank capitalization. Here’s another critique:

Capital gains on a private equity investment reflect any value added in restructuring the company, for example by raising revenues and increasing margins. These gains should, to a certain extent, be determined by the skill of the general partner in setting strategy and, in some cases, introducing new management. But they are also a function of deal leverage: in certain cases, the total cost of an acquisition will fall with the amount of debt funding used, implying that returns can be increased through greater leverage.[Footnote]

[Footnote reads:] This results from a failure of the Modigliani-Miller (M-M) Capital Irrelevance Theorem (1958). A failure of M-M rests on there being financial frictions that distort the relationship between the cost of debt and the amount of equity. If capital markets were fully efficient, the capital structure of a transaction would have no impact on its overall cost of funding. A variety of information and incentive problems and policy distortions (for example the tax deductibility of debt) are widely believed to cause deviations from this theoretical equilibrium.

That paper, by the way, had the usual things to say about private equity:

Private equity fund performance and leverage

Data published by trade bodies (for example, the British Venture Capital Association and European Venture Capital Association) show that buyout fund returns consistently outperform other forms of private equity investment, as well as other, alternative, asset classes.

Academic studies, however, reveal more mixed results. For example Kaplan and Schoar (2005) and Phalippou and Gottschalg (2009) show that private equity funds earn gross returns that exceed the S&P 500 average, but that once fees are taken into account, the net return is equal to or lower than S&P 500 average returns.

Axelson, Strömberg and Weisbach (2009) highlight the procyclical nature of the private equity industry, with a theoretical paper arguing that general partners have the incentive to invest in ‘bad deals’ in periods of loose credit conditions. A follow-up empirical paper by Axelson et al (2012) finds that variation in economy-wide credit conditions is the main determinant of leverage in buyouts, and that greater deal leverage is associated with higher deal values and lower investor returns.

That paper appeared in The Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin. One interesting point they made was:

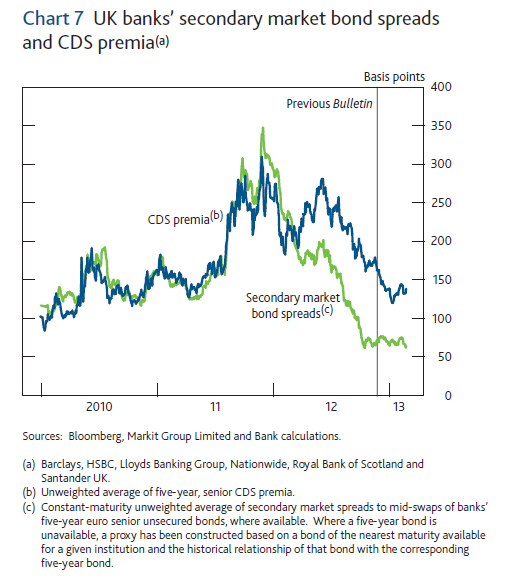

The lack of primary issuance has made it difficult to know for certain at what cost UK banks would be able to finance themselves were they to issue new debt. Available secondary market bond spreads imply that there has been little change in the cost of market funding over the period (Chart 7).

Meanwhile, UK bank credit default swap (CDS) premia, which represent the cost of insuring against default on bank debt, and are sometimes used as an indicative measure of long-term wholesale market funding costs, have fallen (Chart 7). But they remain well above comparable secondary market bond spreads. That gap reflects, in large part, the lack of supply of cash bonds, in conjunction with limited arbitrage between the cash and CDS markets. On balance, while contacts tend to consider secondary market spreads to be a better proxy of bank funding costs than CDS, it may be that secondary spreads would rise were banks to begin to issue more debt.

Stacey Anderson, Jean-Philippe Dion and Hector Perez Saiz have published a BoC Working Paper titled To Link or Not To Link? Netting and Exposures Between Central Counterparties:

This paper provides a framework to compare linked and unlinked CCP configurations in terms of total netting achieved by market participants and the total system default exposures that exist between participants and CCPs. A total system perspective, taking both market participant and CCP exposures into account, is required to answer an important policy question faced by some smaller jurisdictions: whether or not to consider linking a domestic CCP with one or more offshore CCPs. Generally, a single global CCP results in the lowest total system exposure as it allows for multilateral netting across all participants while avoiding the creation of inter-CCP exposures via links. However, global clearing may not be appropriate for all markets. Using a two country model, with a global CCP serving both markets and a local CCP clearing only domestic country participants’ transactions, we show that establishing links between two CCPs leads to higher exposures for the domestic CCP and can result in a decrease in overall netting efficiency and higher total system exposures when the number of participants at the local CCP is small relative to the number of participants at the global CCP. As the relative weight applied by decision makers to CCP exposures as compared to market participants’ exposures increases, so does the number of domestic participants required to make the linked case preferred from a total system perspective. Our results imply that the establishment of a link between a small domestic CCP and a larger global CCP is unlikely to be desirable from a total system perspective in the majority of cases.

…

Establishing links between CCPs in di¤erent jurisdictions could allow any of the above mentioned lost netting opportunities to be regained. Links are contractual agreements whereby two CCPs agree to multilaterally net exposures across their combined membership. Market participants, through their access to a linked domestic CCP, would therefore net exposures across a broader range of counterparties. The creation of links between CCPs does, however, pose challenges. By creating credit exposures between CCPs themselves, links create new channels for risk propagation. If a linked CCP were to default, the surviving CCP would need to ful ll the contractual obligations of cleared contracts to its members. Although not the subject of this paper, links may also create oversight challenges due to additional operational, legal and liquidity risks and increase complexity while reducing the transparency of exposures in the clearing system (CGFS (2011)).

I am pleased to see an acknowledgement that placing all of one’s eggs in a single Too Big To Fail basket is not necessarily a wonderful idea. Perhaps at some point the Bank will sponsor research into risk propogation via CCPs, but I’m not holding my breath on that one.

There’s an interesting point in Rohinton Medhora’s Global rankings: Although inequality between countries is falling, inequality within countries is rising:

>First, integral to the rise of the South is the growth of a middle class the world over. Citing a Brookings Institution study, the UN report estimates that the middle class numbered 1.8 billion in 2009, about one billion of whom lived in Europe and North America. Globally, the number is expected to rise to 3.3 billion in 2020 and 4.9 billion in 2030, the entire growth occurring in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

At the same time, although inequality between countries is falling, inequality within countries – especially the growth success stories such as China and India – is rising.

Just like their counterparts in developed countries, policymakers in developing countries will increasingly be preoccupied with managing middle-class vulnerability. Their challenge will be to fight inequality, not poverty, so as to preserve political stability.

So now, instead of the also-rans in rich countries living well by sponging off the local hot-shots at the expense of everybody in poor countries, we now have more localized inequality that can’t be enforced militarily. It will be most interesting to see how the localized tension plays out…

On an obscurely related note, I had great fun today arguing in favour of a downtown casino in the Globe’s comments section. My comment is the most disliked comment of all – the place of honour!

DBRS confirmed Enbridge Gas Distribution at Pfd-2(low):

EGD’s low business risk profile is supported by a large customer base (approximately two million customers, the largest in Canada), which has allowed the Company to achieve operational efficiency and generate stable earnings and cash flow. In 2013, the rebasing year, EGD’s approved return on equity increased to 8.93% (8.39% in 2012) and distribution rates increased to $1,021 million ($1,004 million in 2012). However, the deemed equity component of the Company’s capital structure remained unchanged at 36%. The Company benefits from a stable regulatory system, having no exposure to gas price risk in Ontario, where it generates approximately 98% of its revenue. EGD’s franchise area (largely in the Greater Toronto Area) is viewed as one of the most rapidly growing and economically strong service areas in Canada. Approximately 94% of the Company’s earnings are generated from relatively stable regulated distribution, transportation and storage business. The remainder is generated from the unregulated storage business, which benefits from strong demand due to its strategic locations.

Note that Enbridge Gas Distribution is a different company than Enbridge Inc., which is its parent:

The Company owns 100% of the outstanding common shares of EGD; however, the four million Cumulative Redeemable EGD Preferred Shares held by third parties are entitled to a claim on the assets of EGD prior to the common shareholder. The preferred shares have no fixed maturity date and have floating adjustable cash dividends that are payable at 80% of the prime rate. EGD may, at is option, redeem all or a portion of the outstanding shares for $25 per share plus all accrued and unpaid dividends to the redemption date. As at December 31, 2012, no preferred shares have been redeemed.

EGD’s Annual Report (SEDAR) states these are:

Group 3, Series D, Fixed / Floating Cumulative Redeemable

Convertible

There are four million oustanding at $25.

It was a mixed day for the Canadian preferred share market, with PerpetualPremiums up 11bp, FixedResets down 13bp and DeemedRetractibles gaining 4bp. Volatility was low. Volume was below average.

| HIMIPref™ Preferred Indices These values reflect the December 2008 revision of the HIMIPref™ Indices Values are provisional and are finalized monthly |

|||||||

| Index | Mean Current Yield (at bid) |

Median YTW |

Median Average Trading Value |

Median Mod Dur (YTW) |

Issues | Day’s Perf. | Index Value |

| Ratchet | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.3698 % | 2,624.6 |

| FixedFloater | 4.13 % | 3.47 % | 31,598 | 18.34 | 1 | -0.4329 % | 3,937.4 |

| Floater | 2.55 % | 2.83 % | 87,558 | 20.16 | 5 | 0.3698 % | 2,833.9 |

| OpRet | 4.82 % | 3.11 % | 59,413 | 0.29 | 5 | 0.0466 % | 2,600.0 |

| SplitShare | 4.28 % | 4.04 % | 719,064 | 4.21 | 4 | -0.1200 % | 2,939.5 |

| Interest-Bearing | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.0466 % | 2,377.4 |

| Perpetual-Premium | 5.20 % | 1.81 % | 90,030 | 0.13 | 31 | 0.1142 % | 2,361.2 |

| Perpetual-Discount | 4.84 % | 4.83 % | 163,259 | 15.79 | 4 | 0.0610 % | 2,662.5 |

| FixedReset | 4.90 % | 2.67 % | 288,073 | 3.47 | 80 | -0.1263 % | 2,509.8 |

| Deemed-Retractible | 4.87 % | 2.31 % | 135,994 | 0.36 | 44 | 0.0441 % | 2,446.0 |

| Performance Highlights | |||

| Issue | Index | Change | Notes |

| MFC.PR.G | FixedReset | -1.13 % | YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Call Maturity Date : 2016-12-19 Maturity Price : 25.00 Evaluated at bid price : 26.30 Bid-YTW : 2.93 % |

| CIU.PR.A | Perpetual-Premium | 1.12 % | YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Limit Maturity Maturity Date : 2043-03-15 Maturity Price : 24.89 Evaluated at bid price : 25.23 Bid-YTW : 4.57 % |

| BAM.PR.C | Floater | 2.55 % | YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Limit Maturity Maturity Date : 2043-03-15 Maturity Price : 18.47 Evaluated at bid price : 18.47 Bid-YTW : 2.83 % |

| Volume Highlights | |||

| Issue | Index | Shares Traded |

Notes |

| BNA.PR.C | SplitShare | 78,546 | RBC crossed blocks of 23,400 and 50,000, both at 24.80. YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Hard Maturity Maturity Date : 2019-01-10 Maturity Price : 25.00 Evaluated at bid price : 24.83 Bid-YTW : 4.53 % |

| BAM.PR.M | Perpetual-Discount | 46,799 | Scotia crossed 35,600 at 24.52. YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Limit Maturity Maturity Date : 2043-03-15 Maturity Price : 24.03 Evaluated at bid price : 24.50 Bid-YTW : 4.83 % |

| PWF.PR.S | Perpetual-Discount | 44,488 | Recent new issue. YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Limit Maturity Maturity Date : 2043-03-15 Maturity Price : 24.66 Evaluated at bid price : 25.06 Bid-YTW : 4.81 % |

| TRP.PR.D | FixedReset | 40,605 | Recent new issue. YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Limit Maturity Maturity Date : 2043-03-15 Maturity Price : 23.28 Evaluated at bid price : 25.58 Bid-YTW : 3.55 % |

| BAM.PR.R | FixedReset | 36,190 | Scotia crossed 30,000 at 26.78. YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Call Maturity Date : 2016-06-30 Maturity Price : 25.00 Evaluated at bid price : 26.67 Bid-YTW : 3.19 % |

| CM.PR.E | Perpetual-Premium | 32,759 | Nesbitt crossed 25,000 at 25.82. YTW SCENARIO Maturity Type : Call Maturity Date : 2013-04-14 Maturity Price : 25.00 Evaluated at bid price : 25.77 Bid-YTW : -21.90 % |

| There were 25 other index-included issues trading in excess of 10,000 shares. | |||

| Wide Spread Highlights | ||

| Issue | Index | Quote Data and Yield Notes |

| IAG.PR.F | Deemed-Retractible | Quote: 26.90 – 27.37 Spot Rate : 0.4700 Average : 0.2598 YTW SCENARIO |

| MFC.PR.G | FixedReset | Quote: 26.30 – 26.58 Spot Rate : 0.2800 Average : 0.1774 YTW SCENARIO |

| MFC.PR.F | FixedReset | Quote: 25.46 – 25.74 Spot Rate : 0.2800 Average : 0.1828 YTW SCENARIO |

| PWF.PR.H | Perpetual-Premium | Quote: 25.99 – 26.24 Spot Rate : 0.2500 Average : 0.1591 YTW SCENARIO |

| RY.PR.Y | FixedReset | Quote: 26.77 – 26.99 Spot Rate : 0.2200 Average : 0.1372 YTW SCENARIO |

| TRI.PR.B | Floater | Quote: 24.02 – 24.36 Spot Rate : 0.3400 Average : 0.2578 YTW SCENARIO |

[…] has been a lot of yammering about income inequality in the past few years, as I mentioned on March 15. I’ve found some more source data: In the next calculation, the world Gini index is […]