The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has released Staff Report 421 by Tobias Adrian, Arturo Estrella, and Hyun Song Shin titled Monetary Cycles, Financial Cycles, and the Business Cycle:

One of the most robust stylized facts in macroeconomics is the forecasting power of the term spread for future real activity. The economic rationale for this forecasting power usually appeals to expectations of future interest rates, which affect the slope of the term structure. In this paper, we propose a possible causal mechanism for the forecasting power of the term spread, deriving from the balance sheet management of financial intermediaries. When monetary tightening is associated with a flattening of the term spread, it reduces net interest margin, which in turn makes lending less profitable, leading to a contraction in the supply of credit. We provide empirical support for this hypothesis, thereby linking monetary cycles, financial cycles, and the business cycle.

I’ve never really been to comfortable with the idea that expectations inverts the yield curve – it seems to me to be asking too much of the world – expectations implies forecasting and forecasting, at least in my book, implies “wrong”. I’m a much bigger fan of the “roundaboutness” process, whereby a slowdown in consumer demand causes goods to pile up at each stage of the production cycle, which means that vendors of these goods have to borrow short term funds to finance the unexpected inventory, which drives up short rates and, as production slows down, also results in a general economic slowdown.

In other words, the curve flattening and the economic cycle are not causally related, but are both results of the same cause; it’s just that the yield curve reacts quicker. This explanation leave out the role of central banks, but I like it as the ‘unfettered free market’ explanation; central banks are simply there to smooth the extremes.

However, the authors of this paper put the central banks front and centre and seek to understand how the central bank action affects subsequent events – naturally enough, since that’s their job:

In this paper, we offer a possible causal mechanism that operates via the role of financial intermediaries and their active management of balance sheets in response to changing economic conditions. Banks and other financial intermediaries typically borrow in order to lend. Since the loans offered by banks tend to be of longer maturity than the liabilities that fund those loans, the term spread is indicative of the marginal profitability of an extra dollar of loans on intermediaries’ balance sheets. For any risk premium prevailing in the market, the compression of the term spread may mean that the marginal loan becomes uneconomic and ceases to be a feasible project from the bank’s point of view. There will, therefore, be an impact on the supply of credit to the economy, and, to the extent that the reduction in the supply of credit has a dampening effect on real activity, a compression of the term spread will be a causal signal of subdued real activity. Adrian and Hyun Song Shin (2009 a, b) argue that the reduced supply of credit also has an amplifying effect due to the widening of the risk premiums demanded by the intermediaries, putting a further downward spiral on real activity.

We explore this hypothesis, and present empirical evidence consistent with it.

They claim their results are relevant to the “Greenspan Conundrum”:

Our results shed light on the recent debate about the “interest rate conundrum.” When the FOMC raised the Fed Funds target by 425 basis points between June 2004 and June 2006 (from from 1 to 5.25 percent), the 10-year Treasury yield only increased by 38 basis points over that same time period (from 4.73 to 5.11 percent). Greenspan (2005) referred to this behavior of longer term yields as a conundrum for monetary policy makers. In the traditional, expectations driven view of monetary transmission, policy works as increases in short term rates lead to increases in longer term rates, which ultimately matter for real activity.

Our findings suggest that the monetary tightening of the 2004-2006 period ultimately did achieve a slowdown in real activity not because of its impact on the level of longer term interest rates, but rather because of its impact on the slope of the yield curve. In fact, while the level of the 10-year yield only increased from 38 basis points between June 2004 and 2006, the term spread declined 325 basis points (from 3.44 to .19 percent). The fact that the slope flattened meant that intermediary profitability was compressed, thus shifting the supply of credit, and hence inducing changes in real activity. The .19 percent at the end of the monetary tightening cycle is below the threshold of .92 percent, and, as a result, a recession occurred within 18 months of the end of the tightening cycle (the NBER dated the start of the recession as December 2007). The 18 month lag between the end of the tightening cycle, and the beginning of the recession is within the historical length.

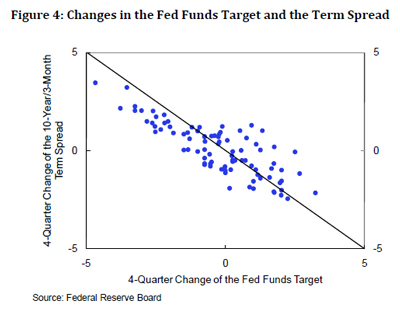

They show a strong relationship between Fed action and the term spread:

The important impact of changes in the Fed Funds target is not on the level of longer term interest rates, but rather on the slope of the yield curve. In fact, Figure 4 below shows that there is a near perfect negative one-to-one relationship between 4-quarter changes of the Fed Funds target and 4-quarter changes of the term spread (the plot uses data from 1987q1 to 2008q3). Variations in the target affect real activity because they change the profitability of financial intermediaries, thus shifting the supply of credit.