Neil Reynolds of the Globe had an interesting column today, Why governments can’t stop market crashes:

The formats for Prof. Smith’s market experiments vary. In one version, a number of people (traders) are given the same investment opportunity – an investment, say, that pays a 24-cent dividend every four weeks for 60 weeks. The guaranteed return is thus $3.60. In the lab setting, the times get compressed; the dividend is paid every four minutes. The traders engage in the computer-assisted buying and selling of this income stream. The process may be repeated, with variations, 15 times in a single session. Invariably, as Prof. Smith (and other economists) have repeatedly shown, traders bid each other up well beyond the actual worth of the investment. In 90 per cent of the sessions, trading ends in market crashes. Author and editor Virginia Postrel, by the way, has written a lucid and illuminating account of this research (“Pop Psychology”) in the December issue of The Atlantic magazine. Experimental economics demonstrates that people don’t normally buy and sell assets based on fundamental worth. People normally are momentum traders, trying simply to buy low and to sell high – a process that, repeated enough times, must eventually end in crashes. Laboratory research by Dutch economist Charles Noussair shows that the lab traders who make the most money are not people who determine fundamental worth; they are people who buy a lot of assets at the beginning of a trading cycle and then sell out midway through the game.

Dr. Smith’s recent paper is available through SSRN: Financial Bubbles: Excess Cash, Momentum, and Incomplete Information:

The intricate relationship between momentum and liquidity may be the chief reason for the sudden changes that occur in the markets without any apparent rationale. The overvaluation of an asset, for example, may continue as an overreaction to some new information. A small trend that is thereby established leads to buying on the part of the momentum traders. This in turn leads to a more sustained trend that continues until the available cash is too small in comparison with the asset prices. The rally then runs out of steam and appears to turn abruptly and unpredictably without any new information on fundamentals.

…

In summary, stock and other asset prices are influenced by factors beyond the market’s realistic assessment of value. The level of cash available for investment in a particular type of investment appears to be chief among them.

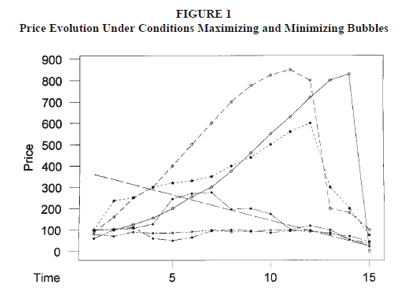

Note: The price evolution is shownfor six experiments, along with the straight line representing the fundamental value (which declines from $3.60 to $0.24). In the three experiments, marked by circles, in which prices soar far above the fundamental value, there is an excess of cash, the dividends are distributed at the end of each period (adding more cash) and there is a closed book so that traders do not know the entire bid–ask book. In the experiments marked by diamonds, the opposite conditions prevail, and prices remain low and there is no bubble.

I’m not sure how I can use this information, but the paper was fascinating anyway! In the meantime, the data appear to support the idea that central banks should lean against asset bubbles – the authors’ note:

In terms of world markets, the experiments suggest that the “easy money” policies of central banks lead to higher prices in financial markets. Economists often regard a nation’s stock market as a barometer of the strength of the economy, so a rising market is considered a good omen. However, from our experimental perspective, a rising market and high valuations may signify an overly relaxed monetary policy, in which assets (rather than common goods) are becoming inflated and pose a boom–bust threat.

It is generally acknowledged that central banks should not attempt to influence stock market prices, for doing so would defeat the purpose of a free market. Yet, from our perspective, the actions of central banks have a profound influence on the price levels of markets. The expansion of price/earnings ratios in U.S. stocks during the mid-1990s may have been enhanced by the Federal Reserve’s easing of monetary policy in response to the savings and loan crisis. Similarly, the Fed’s easing of interest rates during the fall of 1998, this time in response to the insolvency of Long Term Capital Management, and the precautionary increase in liquidity in anticipation of a Year 2000 problem, occurred during a time of economic expansion and may have contributed to the bubble of 1999.

[…] Street met the demand of blind investors. What’s unusual about that? I have also noted some academic experimental work indicating that the price of an asset tends to increase to the money available to buy it, […]