A question in the comments to my old post A Structural Model of Contingent Bank Capital led me to look up what Prof. George Pennacchi has been doing lately; together with Theo Vermaelen and Christian C. P. Wolff he has written a paper titled Contingent Capital: The Case for COERCs:

In this paper we propose a new security, the Call Option Enhanced Reverse Convertible (COERC). The security is a form of contingent capital, i.e. a bond that converts to equity when the market value of equity or capital falls below a certain trigger. The conversion price is set significantly below the trigger price and, at the same time, equity holders have the option to buy back the shares from the bondholders at the conversion price. Compared to other forms of contingent capital proposed in the literature, the COERC is less risky in a world where bank assets can experience sudden, large declines in value. Moreover, the structure eliminates concerns of an equity price “death spiral” as a result of manipulation or panic. A bank that issues COERCs also has a smaller incentive to choose investments that are subject to large losses. Furthermore, COERCs reduce the problem of “debt overhang,” the disincentive to replenish shareholders’ equity following a decline.

The basic justification for the COERCs is:

In contrast to the Credit Suisse coco bond [with accounting and regulatory triggers], the trigger is based on market value based leverage ratios, which are forward looking, rather than backward looking, measures of financial distress. It also means that at the time of the triggering event the stock price is known, unlike in the case of coco bonds with accounting based capital ratio triggers. As the trigger is driven by the market and not by regulators, regulatory risk is avoided. The conversion price is set at a large discount from the market price at the time of conversion, which means that conversion would generate massive shareholder dilution. However, in order to prevent this dilution, shareholders have an option to buy back the shares from the bondholders at the conversion price. In practice, what will happen is that when the trigger is reached, the company will announce a rights issue with an issue price equal to the conversion price and use the proceeds to repay the debt. As a result, the debt will be (almost) risk-free. In our simulations, we show that it is possible to design a COERC in such a way that the fair credit spread is 20 basis points above the risk-free rate. So although the shareholders are coerced to repay the debt, the benefit from this coercion is reflected in the low cost of debt as well as the elimination of all direct and indirect costs of financial distress. Although at the time of the trigger, the company will announce an equity issue, there is no negative signal associated with the issuance as the issue is the automatic result of reaching a pre-defined trigger.

Market based triggers are generally criticised because they create instability: bond holders have an incentive to short the stock and trigger conversion. Moreover, the fear of dilution may encourage shareholders to sell their shares so that the company ends up in a self-fulfilling death spiral. However, because in a COERC shareholders have pre-emptive rights in buying the shares from the bondholders, they can undo any conversion that is result of manipulation or unjustified panic. Moreover, because bondholders will generally be repaid, they have no incentive to hedge their investment by shorting the stock when the leverage ratio approaches the trigger, unlike the case of coco bonds where bondholders will become shareholders after the triggering event. The design of the contract also discourages manipulation by other bondholders. Bolton and Samama (2010) argue that other bond-holders may want to short the stock to trigger conversion, in order to improve their seniority. However, because the COERCs will be repaid in these circumstances such activity will not improve other bondholder’s seniority.

Further justification is given as:

Our objective is to propose an alternative, an instrument that a value maximizing manager would like to issue, without being forced by regulators. Companies are coerced to issue equity and repay debt by fear of dilution, not by the decision of a regulator. Imposing regulation against the interest of the bank’s shareholders will encourage regulatory arbitrage and may also reduce economic growth.6 If bankers, on the other hand, can be convinced that issuing contingent capital increases shareholder value, then any regulatory “encouragement” to issue these securities will be welcomed. Our proposal is therefore more consistent with a free market solution to the general problem that debt overhang discourages firms from recapitalizing when they are in financial distress. Hence the COERC should be of interest to any corporation where costs of financial distress are potentially important.

It seems like a very good idea. One factor not considered in the paper is the impact on equity investors.

Say you have an equity holding in a bank that has a stock price (and the fair value of the stock price) slightly in excess of the trigger price for its COERCs. At that point, buyers of the stock (and continuing holders!) must account for the probability that the conversion will be triggered and their will be a rights issue. Therefore, in order to avoid dilution, they must not only pay the fair market value for the stock, but they must also have cash on hand (or credit lines) available that will allow them to subscribe to the rights offering; the necessity of having this excess cash will make the common less attractive at its fair market value. This may serve to accelerate declines in the bank’s stock price.

It is also by no means assured that shareholders will be able to sell the rights anything close to their fair value.

A Goldman Sachs research report titled Contingent capital Possibilities, problems and opportunities is also of interest. Canadians panic-stricken by the recent musings in the federal budget (see discussion on April 1, April 2 and April 5) will be fascinated by:

Bail-in is a potential resolution tool designed to protect taxpayer funds by converting unsecured debt into equity at the point of insolvency. Most bail-in proposals would give regulators discretion to decide whether and when to convert the debt, as well as how much.

There is an active discussion under way as to whether bail-in should be a tool broadly applicable to all forms of unsecured credit (including senior debt) or whether it should be a specific security with an embedded write-down feature.

Naturally, this discussion is not being held in Canada; we’re too stupid to be allowed to participate in intelligent discussions.

As might be expected, GS is in favour of market-based solutions and consequent ‘high-trigger’ contingent capital:

Going-concern contingent capital differs substantially from the gone-concern kind. It is designed to operate well before resolution mechanisms come into play, and thus to contain financial distress at an early stage. The recapitalization occurs at a time when there is still significant enterprise value, and is “triggered” through a more objective process with far less scope for regulatory discretion. For investors to view objective triggers as credible, however, better and more-standardized bank disclosures will be needed on a regular basis. Because this type of contingent capital triggers early, when losses are still limited, it can be issued in smaller tranches. This, in turn, allows for greater flexibility in

structuring its terms.When the early recapitalization occurs, control of the firm can shift from existing shareholders to the contingent capital holders, and a change in management may occur. The threat of the loss of control helps to strengthen market discipline by spurring the firm to de-risk and de-leverage as problems begin to emerge. As such, going-concern contingent capital can be an effective risk-mitigating tool.

GS further emphasizes the need to appeal to fixed income investors:

Contingent capital will only be viable as a large market if it is treated as debt

Whether “going” or “gone,” contingent capital will only be viable as a large market if it is treated as debt. This is not just a question of technical issues like ratings, inclusion in indices, fixed income fund mandates and tax-deductibility, though these issues are important. More fundamentally, contingent capital must be debt in order to appeal to traditional fixed income investors, the one market large enough to absorb at least $925 billion in potential issuance over the next decade.

Surprisingly, GS is in favour of capital-based triggers despite the problems:

A capital-based trigger would force mandatory conversion if and when Tier 1 (core) capital fell below a threshold specified either by regulators (in advance) or in the contractual terms of the contingent bonds. We think this would likely be the most effective trigger, because it is transparent and objective. Investors would be able to assess and model the likelihood of conversion if banks’ disclosure and transparency are enhanced. Critically, a capital-based trigger removes the uncertainty around regulatory discretion and the vulnerability to market manipulation that the other options entail.

…

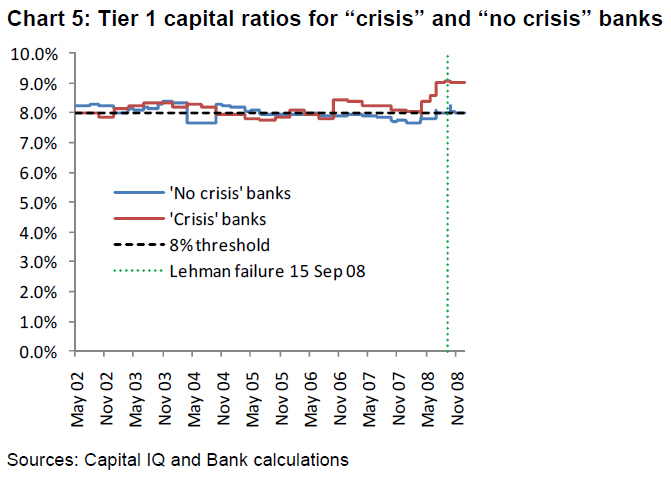

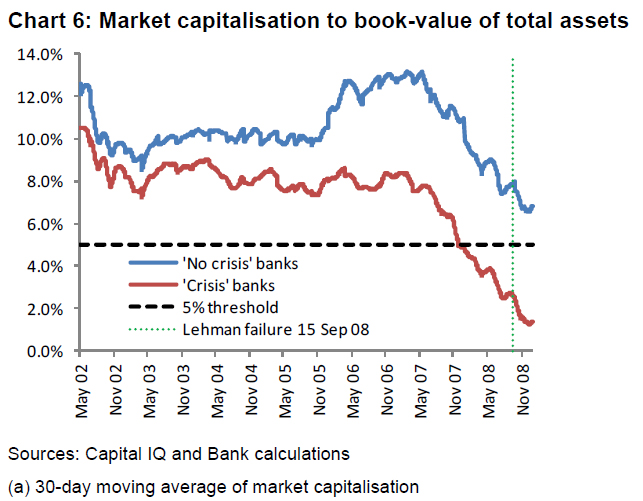

Capital-based triggers are also vulnerable to financial reporting that fails to accurately reflect the underlying health of the firm. Lehman Brothers, for example, reported a Tier 1 capital ratio of 11% in the period before its demise – well above the regulatory minimum and a level most would have considered healthy. The same was true for Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual before they were acquired under distress. We think this issue must be resolved for investors to embrace capital-based triggers.Fortunately there are several ways to make capital ratios more robust, whether by “stressing” them through regulator-led stress tests or by enforcing more rigorous and standardized disclosure requirements that would allow investors to better assess the health of the bank. Such standardized disclosures could relieve regulators of the burden of conducting regular stress tests, and would significantly enhance transparency. The value of stress testing and greater disclosures is one lesson from the financial crisis. The US Treasury’s 2009 stress test illustrates this point vividly. While not perfect, it offered greater

transparency and comparability of bank balance sheets than investors were able to derive from public filings. With this reassurance, investors were willing to step forward and commit capital. The European stress test proves the point as well: it did not significantly improve transparency and thus failed to reassure investors or attract capital.

That is the crux of the matter and I do not believe that the Gordian Knot can be cut in the real world. The US Treasury made their stress test strict and credible because it knew in advance that its banks would pass. The Europeans made their stress test ridiculous and incredible because they knew in advance that their banks would fail.

I liked their succinct dismissal of regulatory triggers:

While flexibility can be helpful, particularly given that no two crises are alike, recent experience shows that some regulators may be hesitant to publicly pronounce that a financial firm is unhealthy, especially during the early stages of distress. There is, after all, always the hope that the firm’s problems will be short-lived, or that an alternative solution to the triggering of contingent capital can be found. Thus a regulator may be unlikely to pull the trigger – affecting not only the firm and all of its stakeholders, but also likely raising alarm about the health of other financial firms – unless it is certain of a high degree of distress. By then, losses may have already risen to untenable levels, which is why this type of trigger is associated with gone-concern contingent capital.

GS emphasizes the importance of the indices:

The inclusion of contingent capital securities in credit indices will also be an important factor, perhaps even more important than achieving a rating. This is because the inclusion itself would attract investors, who otherwise might risk underperforming benchmarks by being underweight a significant component of the index. Credit indices currently do not include mandatorily convertible equity securities, although they can include instruments that allow for loss absorption through a write-down feature. This again contributes to the appeal of the write-down feature (rather than the simple conversion to equity) to most fixed income investors. If contingent capital securities were included in credit indices, this addition would be likely to drive a substantially deeper contingent capital market.

Here in Canada, of course, the usual benchmark is prepared by the TMX, which the regulators allowed to become bank-owned on condition that it improved the employment prospects for regulators. It’s a thoroughly disgraceful system which will blow up in all our faces some days and then everybody will pretend to be surprised.

GS is dismissive of regulatory triggers and NVCC:

A discretionary, “point of non-viability” trigger would likely be attractive to many regulators as it helps them to preserve maximum flexibility in the event of a financial crisis. This can be useful given that no two crises are exactly alike. It could also allow regulators to consider multiple factors – including the state of the overall financial system – when making the decision to pull the trigger. Discretion also gives regulators the opportunity to exercise regulatory forbearance away from the public spotlight.

Yet we believe this preference for discretion and flexibility makes it difficult for regulators to meet one of their most important – yet mostly unspoken – goals, which is to develop a viable contingent capital market. Regulators have certainly solicited feedback from investors, but some seem to believe that simply making contingent capital mandatory for issuers means that investors will buy them. However, from conversations with many investors, we believe that regulators may need to move toward a more objective trigger; if not, the price of these instruments may be prohibitive.

There is another set of participants in a potential contingent capital market: taxpayers. Regulators represent taxpayers’ interests by promoting systemic stability and requiring robust loss-absorption capabilities at individual banks. But the interests of regulators and taxpayers may not always be fully aligned. If taxpayers’ principal goal is to avoid socializing private-sector losses, and to prevent the dislocation of a systemic crisis even in its early stages, then they should want a stringent version of contingent capital – one that converts to equity at a highly dilutive rate, based on an early and objective trigger. The discretion and flexibility inherent in regulatory-triggered gone-concern contingent capital may have less appeal to taxpayers. From their standpoint, gone-concern contingent capital might well have allowed a major financial firm to fail, causing job losses and other disruptions across the financial system. Taxpayers may find the potential risk-reducing incentives created by going-concern contingent capital to be a more robust answer to the problem of too big to fail.

Goldman’s musings on investor preference can be taken as an argument in favour of COERCs:

Traditional fixed-income investors will likely want contingent capital to have a very low probability of triggering, which leads them to prefer an objective, capital-based and disclosure-enhanced trigger. Many investors have indicated their concerns about the challenges of modeling a discretionary trigger: it is very difficult to model the probability of default, the potential loss given default or even the appropriate price to pay for a security that converts under a discretionary and opaque process. Greater transparency is a prerequisite for a capital-based trigger to be seen as credible by investors, because they will need to have greater confidence that banks’ balance sheets reflect reality. We also believe that investors would be more likely to embrace a capital-based trigger if the terms were quite stringent, thereby lowering the probability of conversion.