Accrued Interest has come out in favour of Exchange Traded Credit Default Swaps in a new post:Bailouts, Wall Street, and the Bad Motivator, although he does not go so far as some in claiming that over-the-counter trading should be (effectively) banned.

I addressed a similar exhortation in my post Leverage, Bear Stearns & Econbrowser.

I’m not a proponent of Exchange Trading for CDSs – I can see a useful purpose being served by a clearinghouse, but exchanges are set up so that non-institutional players get to play. I will defer to any those with better information, but I don’t sense any clamour from retail to trade in Credit Swaps … several attempts to set up an exchange have died on the vine (see Update #4 to the ‘Econbrowser’ post) although I don’t know to what extent retail was invited to the party. By me, exchange trading will involve enormous listing fees and a huge bureaucracy to list a plethora of CDSs that will trade by appointment only at 100bp spreads. What’s the point?

While I have great respect for Accrued Interest, I think there are a number of misconceptions embedded in his post:

Had Bear Stearns been allowed to fail, banks world wide would have lost their counter-party on various derivative transactions.

Well, no. As I pointed out on the ‘Econbrowser’ post:

as far as the counterparties were concerned, their counterparty was not BSC per se, but wholly-owned, independently capitalized, highly rated subsidiaries of BSC. Just how adequate the capital, accurate the ratings, and ring-fenced the assets actually were is something I am not qualified to judge – seeing as how I haven’t even seen any of the guarantees and financial statements in question. But neither, it would appear, has Prof. Hamilton.

I should note that I brought this up in the comments to the Accrued Interest post:

JH: I don’t believe that this is correct. See my post Leverage, Bear Stearns & Econbrowser

…

James: I read your piece at the time. My reaction is that we don’t really know what would have happened if BSC actually declared bankruptcy.

Accrued Interest goes on to postulate:

Let’s say you allow Bear Stearns to fail and that caused XYZ bank to fail. Is that capitalism? Forcing XYZ to suffer for the sins of Bear Stearns?

I say … yes, that is capitalism, but no, it’s not forcing XYZ to suffer for the sins of BSC. It is forcing XYZ to suffer for their own sins in not demanding adequate collateralization from BSC when their position started winning (if XYZ’s trade was losing, BSC’s bankruptcy would not affect them). If XYZ failed, it would be due not only to insufficient collateralization, not only due to their extending far too great a credit line to BSC, but also a failure of regulation in not having previously assigned a capital charge to XYZ that reflected their risk.

When a position – of any kind – gets marked-to-market, P&L changes. If the position is winning and profit increases, then shareholders’ equity increases. So far, so good. But the credit exposure to the counterparty has also increased … it’s a loan to the counterparty and gets charged as such. In any reasonable regime, collateralization will reduce the risk measured from the gross exposure. It may, upon sober review of the evidence, be deemed necessary to fiddle with these various calculations of Risk Weighted Assets, but I fail to see a need for anything more.

Next! Accrued Interest then claims:

The first step is obvious. Credit-default swaps need to be exchanged-traded.

I don’t see that at all. If we accept for a moment that counter-party risk is out of hand (I don’t accept it, but let’s continue the discussion) then exchange trading is only one option. The option that minimizes change would be a clearing-house, whereby the clearing house acts as the counterparty for all trades and the clearing-house itself is guaranteed by each of its members. An exchange would incorporate this function, but the functionality does not require an exchange.

Accrued Interest continues:

There would be some relatively simple ways to bring such a thing about. What if banks were required to recognize the credit risk of their counter-parties directly?

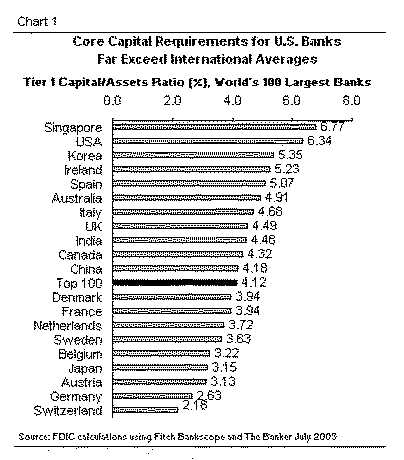

They are. Assiduous Readers will remember that I looked at Scotiabank’s capitalization today. According to page 23 of their supplementary information, their Basel-I Risk-Weighted-Assets of 252.8-billion includes 240.5-billion of credit risk, which includes 34.0-billion of “Off-Balance Sheet Assets – Indirect Credit Instruments”. If we go to the OSFI website and look at Scotia’s 1Q08 “BCAR Derivative Components”, we find that they have Credit Derivative Contracts [OTC] of $108.9-billion outstanding (and those are REAL dollars, none of that sub-par American muck) giving rise to a replacement cost of $3.1-billion and a credit equivalent amount of $8.1-billion which (when combined with other derivatives) gives rise to a Risk-Weight-Equivalent of $10.7-billion … just over 4.2% of their total risk-weighted assets.

One may wish to twiddle with the numbers – converting the notional amounts and unrealized P&L in different ways to get different Risk-Weighted-Assets. But it is not correct to imply that the credit risk is not currently recognized.

Accrued Interest continues:

I think back to banks needing to reserve for losses dealt to them by XLCA/FGIC/Ambac/MBIA’s potential failure to perform on CDS contracts.

Now, this is a legitimate concern. According to OSFI Guidelines (Section 3.1.5, page 31) claims on Deposit Taking Banks of an AAA to AA- sovereign carry a risk-weight of 20%, which is the same as similarly graded corporates (section 3.1.7). Single A comes at 50%, BBB+ to BB- is 100% and let’s not go further.

If we look at the quarterly report for CM, we find:

During the quarter, we recorded a charge of US$2.30 billion ($2.28 billion) on the hedging contracts provided by ACA (including US$30 million ($30 million) against contracts unrelated to USRMM unwound during the quarter) as a result of its downgrade to non-investment grade. As at January 31, 2008, the fair value of derivative contracts with ACA net of the valuation adjustment amounted to US$70 million ($70 million). Further charges could result depending on the performance of both the underlying assets and ACA.

The problem here is: they (effectively) made a loan of USD 2.37-billion to ACA and have now written down 2.30-billion of it. Why were they making (effective) loans of this size to a single (effective) borrower?

It is my understanding that many of the monolines were refusing to write protection unless they were exempted from collaterallization, on the grounds that they were AAA rated. It is my further understanding that this was just fine by some of the banks and brokerages. Well, it’s a business decision. As long as it’s adequately charged, it can remain a business decision.

I will certainly agree that loans of this size to a single party (equivalent to about one-sixth of their October 2007 capital) should have attracted a concentration charge, on top of the regular charge for corporate debt. But this – the existence or lack thereof of concentration charges in capital requirements – is what we need to talk about, without jumping into mandatory exchange trading of CDSs!

Accrued Interest concludes:

Why not just make them reserve a larger amount for this possibility up front? Efforts to start an exchange would begin the next day.

Well … maybe. To the extent that the exchange’s clearing-house’s credit would be better than the sum of its sponsoring parts, it is entirely reasonable to suppose that $1-billion exposure to a clearing-house would be charged at less than 10x$100-million to its individual members. It may also be assumed that netting and novation will be facilitated with a clearing house, which will further reduce exposure.

Whether or not the improvement in credit quality and consequent (we hope) reduction in capital requirements balances the guaranteed extra costs and reduced flexibility implied by a clearing-house is something that can be discussed … and the decision regarding institutional participation in such a scheme becomes just another business decision. But let’s see some numbers first.

Update, 2008-5-28: Naked Capitalism reprints a Financial Times rumour of an announcement tomorrow. This will, as far as I can tell, make formal a proposal aired in April that has been well reported:

“There is not one element that is going to solve all the problems, but it is one piece of the puzzle that will help us create a more robust framework. The timing is right – whether it will be successful or not, only time will show,” says Athanassios Diplas, chief risk officer and deputy chief operating officer, global credit trading, at Deutsche Bank, speaking at Isda’s twenty-third annual general meeting in Vienna on April 17.

The initial focus of those involved in the discussions has been on index products. Over time, efforts will extend to single-name CDSs. According to Diplas, this will remove risk from the system and the worry that the failure of one dealer could cause a hazardous shock in the market.

No details were given on a time frame for when a central clearing house would be established, but Diplas says the admission criteria for participants would be strict. “The criteria will take into account how well capitalised the firm is, how the risk is dealt with, how the variation margins are going to be posted and what the expected gap risk is going to be. All these issues have to be dealt with carefully – we are not going to jump into something unless we are very confident it will work.”

Update, 2008-6-19: See the market update of June 9 for news of how the proposal is moving along. Accrued Interest has posted another good piece about CDS clearing and exposures.