Accrued Interest has a very good post today regarding S&P’s views on the monolines:

S&P and Moody’s have now both affirmed MBIA. S&P also more or less said they would affirm Ambac as well if the reported $3 billion capital infusion is completed. MBIA’s infamous 14% surplus note is now trading comfortably above par ($101 bid, $104 offer last night). So are we out of the woods with the monolines?

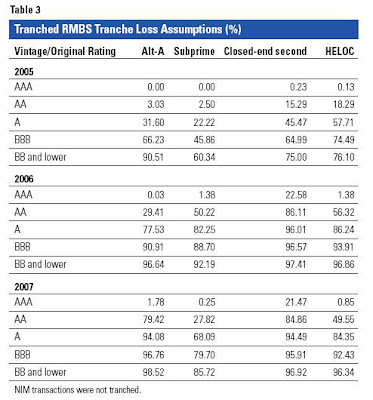

Well let’s start by looking at S&P’s methodology. In short, S&P will bestow a AAA rating if they believe an insurer can survive their “stressed” scenario. Here are their assumptions for various types of mortgage-related securities.

……

So all in all, I’d say that’s a pretty stressful scenario.

S&P, with its customary eagerness to become a credit rating agency that charges both the issuers and the subscribers, does not make the full report freely available. But Moody’s has published some notes:

Although losses on the 2006 mortgages are still low – mainly because the loans are still relatively unseasoned and the foreclosure process is taking longer than in previous years – Moody’s expects that they will rise considerably in the next few years. The most significant components of the uncertainty regarding the ultimate loss outcomes are (1) the extent to which loans will be modified and these modifications are successful in preventing defaults, (2) the impact of interest rate resets in 2008 and (3) the strength of the US economy in 2008 and beyond.

In this article, we provide projections of the lifetime average cumulative losses for each of 2006’s quarterly vintages, given each transaction’s current level of losses and delinquencies, and assumptions regarding the “roll rates” into default from various categories of delinquent loans and the severity of losses on loans that default.

…

Moody’s projection for mortgage losses on the 2006 vintage is in the 14-18% range

The Buiter/Sibert column on Barack Obama’s “Patriot Employer Act”, mentioned yesterday, has drawn a lot of comment. Tanta at Calculated Risk has a very entertaining and devastating commentary about Lost Note Affidavits with respect to foreclosures, prompted by a story about legal maneuvering that caught my eye at the time, but went unremarked here. I’ve added some updates to the Crony Capitalism post and have made a little progress on Seniority of Bankers Acceptances.

The rather surprising level of lending by the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB) mentioned here on November 26 was attacked by Nouriel Roubini yesterday, as noted by the WSJ. I found his views on the monolines more interesting:

Similarly, the concern about the writedowns that will follow a downgrade of the monolines is well taken. However, desperate attempt to avoid a rating downgrade of monolines that do not deserve such AAA rating are highly inappropriate as the insurance by these monolines of toxic ABS was reckless in the first place. If public concerns about access to financing by state and local governments during a recession period are warranted it is better to split the monoline insured assets between muni bonds and structured finance vehicle, ring fence the muni component and let the rest be downgraded and accept the necessary writedowns on the structured finance assets. If these necessary writedowns will then hurt financial institutions that hold this “insured” toxic waste so be it as these assets should have never been insured in the first place. The ensuing fallout from the necessary writedown – such as the need to avoid fire sales in illiquid markets – should then be addressed with other policy actions.

I can’t agree with this at all. You can’t just split up a company’s committments – effectively, expropriating the rights of whoever’s guaranteed by the “bad” side – just on the basis of which set of guaranteed counterparties are nicer people. Should the monolines fail – and they’re not close to that yet, they’re merely close to losing their AAA ratings – and need to be recapitalized, then company splits can make sense. But not until their equity has gone to zero!

The hills are alive with the word that Apex & Sitka trusts might fail, costing the Bank of Montreal something like $495-million. DBRS explained in a Feb. 25 press release:

The Trusts were organized to enter into collateralized debt obligation (CDO) transactions, including CDO transactions that employ leverage. As of the date of this press release, 100% of the transactions entered into by the Trusts are LSS transactions. A LSS transaction is a type of transaction where a credit protection seller (such as a Canadian asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) issuer (Conduit) that issues ABCP, extendible commercial paper or floating rate notes) writes credit protection on a tranche of a CDO transaction which is less than 100% collateralized and that will incur its first dollar of loss above the AAA attachment point. Losses to LSS transactions are considered a remote credit risk; however, these transactions exhibit funding risk. LSS transactions include leverage in that the collateral held by the Swap Counterparty will be smaller than the potential maximum exposure under the credit default swap. As such, the credit protection seller may be required to post additional collateral if its exposure under the swap increases.

Well, I’m not going to take a strong view on this. I don’t know how profitable the business was for BMO or how carefully they measured their risk. On the surface, it sounds like just another failed CDPO (“Whoopsy! Long term returns can be interupted by margin calls!”) … but again, I don’t know what risk controls BMO had in place (and leverage of loans is what banks do, right? The difference is that most loans don’t have to be marked-to-panicky-market every day … the bankers exercise judgement, good or bad, as to whether there is permanent impairment). What I do know is: Show me somebody who’s never failed, and I’ll show you somebody who’s never tried.

Another quiet day, with PerpetualDiscounts easing down.

| Note that these indices are experimental; the absolute and relative daily values are expected to change in the final version. In this version, index values are based at 1,000.0 on 2006-6-30 | |||||||

| Index | Mean Current Yield (at bid) | Mean YTW | Mean Average Trading Value | Mean Mod Dur (YTW) | Issues | Day’s Perf. | Index Value |

| Ratchet | 5.52% | 5.53% | 37,758 | 14.6 | 2 | +0.9099% | 1,085.4 |

| Fixed-Floater | 4.97% | 5.65% | 72,802 | 14.70 | 7 | +0.2682% | 1,032.3 |

| Floater | 4.93% | 5.00% | 67,530 | 15.44 | 3 | +0.0240% | 857.1 |

| Op. Retract | 4.80% | 2.14% | 76,782 | 3.12 | 15 | +0.0715% | 1,049.3 |

| Split-Share | 5.27% | 5.15% | 97,812 | 4.06 | 15 | -0.0687% | 1,049.4 |

| Interest Bearing | 6.22% | 6.38% | 57,229 | 3.36 | 4 | +0.2251% | 1,088.4 |

| Perpetual-Premium | 5.70% | 4.16% | 334,582 | 4.32 | 16 | +0.0982% | 1,034.3 |

| Perpetual-Discount | 5.35% | 5.39% | 273,783 | 14.82 | 52 | -0.1060% | 961.8 |

| Major Price Changes | |||

| Issue | Index | Change | Notes |

| LBS.PR.A | SplitShare | -1.9305% | Asset coverage of just under 2.2:1 as of February 21, according to Brompton Group. Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 5.08% based on a bid of 10.16 and a hardMaturity 2013-11-29 at 10.00. |

| BCE.PR.I | FixFloat | -1.2058% | |

| IGM.PR.A | OpRet | -1.1431% | Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 3.92% based on a bid of 26.81 and a call 2009-7-30 at 26.00. |

| BSD.PR.A | InterestBearing | +1.0460% | Asset coverage of just under 1.6+:1 as of February 22, according to Brookfield Funds. Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 6.89% based on a bid of 9.51 and a hardMaturity 2015-3-31 at 10.00. |

| GWO.PR.F | PerpetualPremium | +1.1525% | Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 4.87% based on any of a call on 2010-10-30 at 25.50, on 2011-10-30 at 25.25, or 2012-10-30 at 25.00 … take your pick. |

| WFS.PR.A | SplitShare | +1.1788% | Asset coverage of just under 1.8:1 as of February 21, according to the company. Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 4.57% based on a bid of 10.30 and a hardMaturity 2011-6-30 at 10.00. |

| BAM.PR.K | Floater | +1.1998% | |

| BCE.PR.B | FixFloat | +1.3323% | |

| Volume Highlights | |||

| Issue | Index | Volume | Notes |

| BCE.PR.C | FixFloat | 152,500 | Nesbitt crossed 42,000, then 20,000, then 88,000 within a minute, all at 24.35. |

| BMO.PR.K | PerpetualDiscount | 60,443 | Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 5.33% based on a bid of 24.75 and a limitMaturity. |

| DFN.PR.A | SplitShare | 148,100 | Desjardins crossed 135,000 at 10.25. Asset coverage of just under 2.5:1 as of February 15, according to the company. Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW of 4.85% based on a bid of 10.24 and a hardMaturity 2014-12-1 at 10.00. |

| BCE.PR.R | FixFloat | 50,000 | Nesbitt crossed 50,000 at 24.10. |

| BNS.PR.O | PerpetualPremium | 22,850 | Now with a pre-tax bid-YTW 5.33% based on a bid of 25.65 and a call 2017-5-26 at 25.00. |

There were thirteen other index-included $25-pv-equivalent issues trading over 10,000 shares today.