The Bank of Engand has released the December 2009 Financial Stability Report, with the usual tip-top analysis.

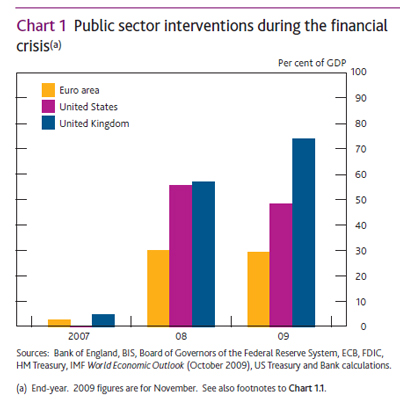

The first chart puts things into perspective: the UK is a smaller economy than the US or the Continent:

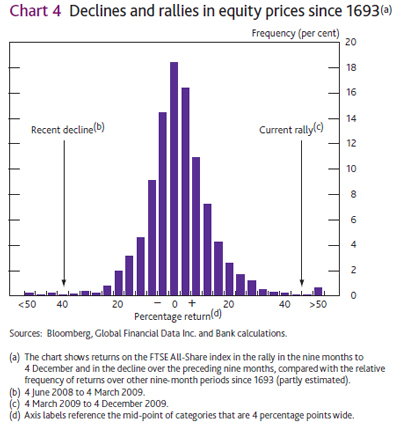

Who but the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street would dare produce an equity returns graph dating back to 1693?

UK banks are strongly encouraged to sell equity:

Despite inevitable short-term costs, there is a strong case for banks acting now to improve balance sheet positions while conditions are favourable. Retaining a higher share of current buoyant earnings could significantly increase banks’ resilience and ability to lend. If discretionary distributions had been 20% lower per year between 2000 and 2008, banks would have generated around £75 billion of additional capital — more than provided by the public sector during the crisis. It is also an opportune time for banks to raise capital externally, extend the maturity of their funding, and develop and implement plans for refinancing substantial sums as official sector support is withdrawn.

The bank is also throwing its weight behind Contingent Capital and leverage caps:

Capital buffers will need to rise, possibly substantially, over the coming years. The quality of banks’ capital also needs to improve. To absorb losses, capital should comprise equity or instruments that convert to equity automatically under pre-defined conditions. To avoid excessive reliance on refined regulatory risk weights, risk-based capital requirements should be accompanied by a mandatory maximum leverage ratio (Box 6).

They’ve done some work to see how much capital should be required going forward:

On average, a pre-crisis Tier 1 capital ratio of around 8.5% would have been needed by banks in the sample to avoid going below a Tier 1 capital ratio of 4% during the crisis (Chart A). Minimum capital requirements are likely to be higher in the future.

A feature of this analysis is the wide variation in results across banks, shown by the distributions in Chart A. Banks with similar pre-crisis Tier 1 capital ratios faced different outcomes in some cases. Even if all banks in the sample had a pre-crisis capital ratio of 8.5%, 40% of the banks would still have breached the 4% Tier 1 capital ratio in-crisis. The highest pre-crisis Tier 1 capital ratio that would have been needed across the sample of banks to maintain a 4% Tier 1 capital ratio in-crisis is around 18%. This variation across banks suggests the need for flexibility in their future capital structure and potentially a higher average buffer. In principle, this could be achieved through greater use of contingent capital (see Section 3).

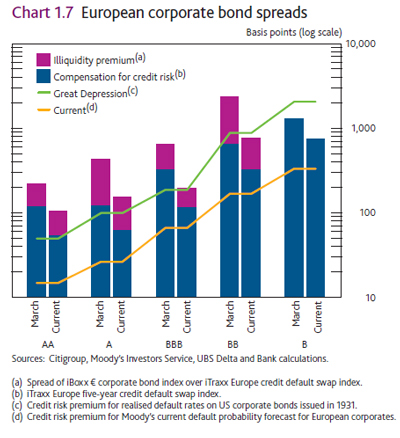

Oddly, they have a chart decomposing credit spreads according to the BoC methodology, which I dislike, as opposed to the Webber & Churm methodology used in the past:

There is no explanation in the report regarding the change.

There are big problems with loan-to-value ratios on commercial property … or there would be if they were recognized!

The sharp declines in capital values have triggered breaches of loan to value (LTV) covenants, with some loans in negative equity. Estimates from the Property Industry Alliance (PIA) suggest that average LTVs could reach 114% by end-2010.

As well as causing covenant breaches, declines in values (and rises in LTVs) will also have reduced firms’ access to credit by reducing the value of the commercial property that they might use as collateral for secured borrowing. Market contacts suggest that banks have been willing, to date, to show forbearance in respect of breaches of LTV covenants. In addition, research by De Montfort University suggests that, while loans are still performing, some lenders have not sought to revalue underlying properties. As a result, the sharp declines in capital values alone had a fairly limited impact on banks.

Footnote: The PIA is an alliance of five property bodies — the British Council for Offices, British Council of Shopping Centres, British Property Federation, Investment Property Forum and Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

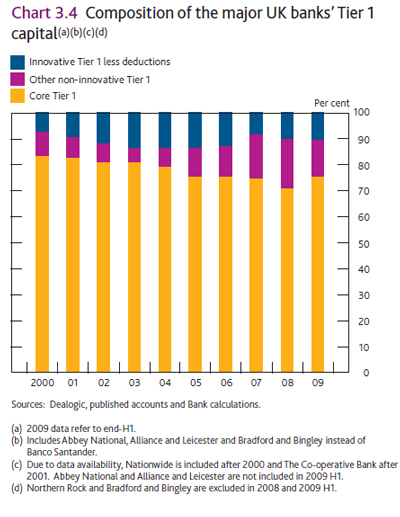

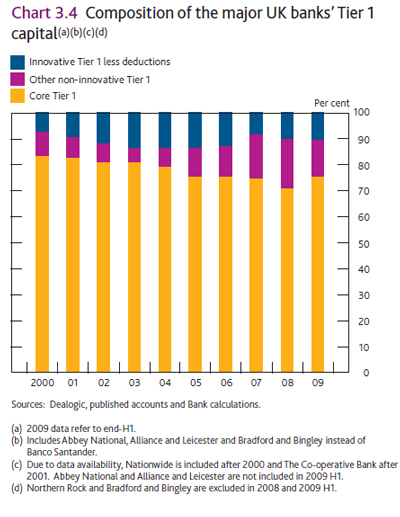

Many will find the commentary on the composition of Tier 1 Capital interesting, particularly given the Canadian limits following OSFI’s debasement of bank capital:

Ahead of the crisis, the composition of banks’ capital shifted away from common equity and reserves (core Tier 1 capital) towards lower-quality instruments (Chart 3.4). Experience during the crisis in the United Kingdom and elsewhere has revealed that these instruments were not always able to absorb losses for going-concern banks.

There is now broad agreement internationally that equity and reserves should form a much larger part of banks’ capital in the future. The Bank believes that no instrument should be classified as going-concern capital if it does not have the same loss-absorbing characteristics as common equity. In practice, this means either that the principal of the instrument can be written down at the same time and to the same extent as common equity, or that the instrument is convertible into equity — so-called ‘contingent capital’.

And now we’re getting into the meaty bit! Contingent Capital is a vital concept for preferred shareholders: I am convinced that the preferred share as we know it is dead; it will all be contingent at some point in the future. Bet a nickel.

On what terms private non-bank investors would be willing to provide such insurance remains unclear. For example, investor appetite may initially be restricted if these instruments are excluded from benchmark indices or are not permitted under certain investment mandates. If, over time, an investor base for such instruments did not develop, this would provide a useful signal that debt investors were unwilling to accept losses on their investments in banks. For contingent capital instruments to be loss-absorbing, their design needs careful consideration. In this respect, the definition of the conversion trigger is crucial. Contingent capital would need to convert automatically, or at the discretion of the regulator, rather than on the initiative of the issuer. Setting the trigger involves balancing the risk of conversion too soon (before capital is needed) and too late (when funding problems may already have emerged). The acceptable level of contingent capital within banks’ capital structure also needs to be considered carefully. Too much convertible debt could increase the risk of a bank equity price ‘death spiral’ — whereby investors may short-sell the stock in anticipation of dilution as the trigger for conversion comes closer.

This constant harping on regulatory discretion really gets on my wick. In a crisis, the pronouncement by a regulator that Bank X is sufficiently endangered that it needs to trigger conversion will be a death sentence. Conversion needs to be automatic, predictable and hedgeable: as I have argued countless times, these conditions are met by setting a trigger-and-conversion price at the time of issue of the non-equity capital (maybe 50% of issue-time common price for Tier 1; 25% for Tier 2). If the common price falls below the trigger price (on a well-defined exchange in a well defined way for a well defined period) then the contingent capital converts at that particular trigger price. Holders who wish to hedge will be able to buy options with their income payments … alternatively, options players may wish to buy the CoCo from the existent holders in order to get the embedded option; this will depend on the market price of the CoCo.

Death Spirals are not an issue if the conversion price is fixed; and become less important as a minimum coversion price increases (e.g., in Canadian Operating Retractible issues, the minimum conversion price is $2, which prevented the IQW.PR.C conversion from becoming a death spiral … although it ultimately made no difference).

The BoE states flatly:

The Bank would support the introduction of a leverage ratio

and this being hard-wired into regulatory rules through Pillar 1, provided that it can be well defined. It will be difficult to set a single standard applicable across different business models and accounting regimes, but it is important to achieve consistent implementation across jurisdictions.

… which, I think, can be taken at face value. Given the tenor of the rest of their discussion, I don’t think they intend to invent problems regarding implementation specifics to mask a distaste for the idea.

I’m not so enthralled with the following:

In a recent Discussion Paper (DP), the Bank contributed to emerging ideas on how such a macroprudential regime could be made operational.(2)

The DP examined the possibility of applying time-varying capital surcharges on banks to dampen cyclical exuberance (the orange bars in the stylised example in Chart 3.13). Raising capital requirements in a credit boom would offer greater self-insurance for the financial system against a subsequent bust. It could also provide incentives for banks to restrain exuberant lending by raising its marginal cost. In addition, the DP suggested that capital surcharges could be imposed on firms to better reflect their individual contribution to systemic risk (the magenta bars in Chart 3.13). These would be based on factors such as firms’ size, complexity, interconnectedness and propensity to cause losses to others through asset fire sales. The key objective would be to lower the probability of default of banks whose failure would impose a large spillover cost on the financial system. Systemic surcharges could also provide incentives for banks to alter their balance sheets or business models, supporting structural initiatives in this area (see Section 3.2).

I don’t support the nod-and-wink model of regulation by any means, and the proposals to give regulators discretion in such matters will only enhance the attractiveness of regulatory capture. Counter-cyclical requirements, yes: have a surcharge on asset growth over the past 5-10 years. Systemic surcharges, yes: have a surcharge on a progressive schedule based on risk-weighte assets. Regulatory discretion? No. Not only can’t the regulators be trusted with that degree of power (NOBODY can be trusted with that degree of power), but it raises the spectre of single-point failure even higher and will make the regulators the mutual plaything of the banks and politicians.

The next part is good. In Canada, we denigrate the shadow-banking sector:

With these objectives in mind, HM Treasury has announced that it intends to publish a discussion paper on developing non-bank lending channels in the United Kingdom, drawing on advice from the FSA and the Bank.(1) Key issues to be considered include identifying necessary improvements to market infrastructure that will help corporate borrowers to access non-bank investors.

One thing I haven’t seen before is the proposal to treat all retail deposits as covered bonds:

One way of ensuring continuity of payment services could be to require banks to invest retail deposits solely in risk-free assets such as government bonds — an approach commonly referred to as ‘narrow banking’. A number of commentators have put forward proposals along these lines in response to the crisis.(1) This could be seen as an extension of arrangements already in place for private banknotes issued by some Scottish and Northern Irish banks. These banks are required to hold cash or credit balances with the Bank of England fully backing their note issuance. These assets cannot be used for any other purpose and would be excluded — or ‘ring-fenced’ — from any insolvency proceeding and reserved for satisfying the claims of note holders.

An arrangement where retail deposits are backed by risk-free assets need not require the creation of dedicated narrow banks, although this could conceivably occur naturally over time. Existing banks could instead be required to segregate their retail deposit books and the assets backing them within their internal structures. The segregated part of a bank would effectively be subject to a 100% liquidity requirement, and would need to be easily extractable from the wider group using available resolution tools. In this way, the integrity of the payment system would be assured, while still allowing banks to exploit economies of scope between payment services and other types of banking activity.