Bernanke has given a speech titled Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble to the Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association:

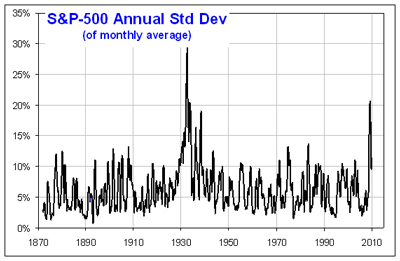

As with regulatory policy, we must discern the lessons of the crisis for monetary policy. However, the nature of those lessons is controversial. Some observers have assigned monetary policy a central role in the crisis. Specifically, they claim that excessively easy monetary policy by the Federal Reserve in the first half of the decade helped cause a bubble in house prices in the United States, a bubble whose inevitable collapse proved a major source of the financial and economic stresses of the past two years.

These assertions have been discussed on PrefBlog, for example Taylor Rules and the Credit Crunch Cause; the seminal paper was discussed on Econbrowser, The Taylor Rule and the Housing Boom. But Bernanke has One Big Problem with blind use of the Taylor Rule:

For my purposes today, however, the most significant concern regarding the use of the standard Taylor rule as a policy benchmark is its implication that monetary policyshould depend on currently observed values of inflation and output.

…

However, because monetary policy works with a lag, effective monetary policy must take into account the forecast values of the goal variables, rather than the current values. Indeed, in that spirit, the FOMC issues regular economic projections, and these projections have been shown to have an important influence on policy decisions (Orphanides and Wieland, 2008).

…

when one takes into account that policymakers should and do respond differently to temporary and longer-lasting changes in inflation, monetary policy following the 2001 recession appears to have been reasonably appropriate, at least in relation to a simple policy rule.

Central to Bernanke’s argument is:

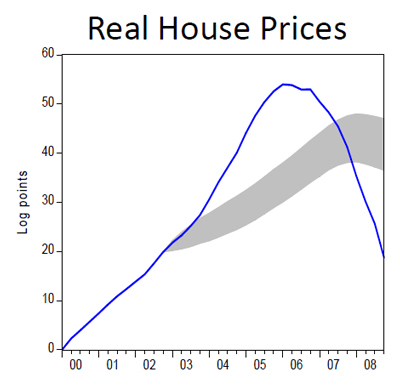

To demonstrate this finding in a simple way, I will use a statistical model developed by Federal Reserve Board researchers that summarizes the historical relationships among key macroeconomic indicators, house prices, and monetary policy (Dokko and others, 2009).

…

The model incorporates seven variables, including measures of economic growth, inflation, unemployment, residential investment, house prices, and the federal funds rate, and it is estimated using data from 1977 to 2002.

…

The right panel of the figure shows the forecast behavior of house prices during the recent period, taking as given macroeconomic conditions and the actual path of the federal funds rate. As you can see, the rise in house prices falls well outside the predictions of the model. Thus, when historical relationships are taken into account, it is difficult to ascribe the house price bubble either to monetary policy or to the broader macroeconomic environment.

One reason he suggests for the decoupling of historical relationships is ARMs and other exotic mortgages:

Clearly, for lenders and borrowers focused on minimizing the initial payment, the choice of mortgage type was far more important than the level of short-term interest rates.

The availability of these alternative mortgage products proved to be quite important and, as many have recognized, is likely a key explanation of the housing bubble.

…

Slide 8 is evidence of a protracted deterioration in mortgage underwriting standards, which was further exacerbated by practices such as the use of no-documentation loans. The picture that emerges is consistent with many accounts of the period: At some point, both lenders and borrowers became convinced that house prices would only go up. Borrowers chose, and were extended, mortgages that they could not be expected to service in the longer term. They were provided these loans on the expectation that accumulating home equity would soon allow refinancing into more sustainable mortgages. For a time, rising house prices became a self-fulfilling prophecy, but ultimately, further appreciation could not be sustained and house prices collapsed. This description suggests that regulatory and supervisory policies, rather than monetary policies, would have been more effective means of addressing the run-up in house prices.

He concludes:

I noted earlier that the most important source of lower initial monthly payments, which allowed more people to enter the housing market and bid for properties, was not the general level of short-term interest rates, but the increasing use of more exotic types of mortgages and the associated decline of underwriting standards. That conclusion suggests that the best response to the housing bubble would have been regulatory, not monetary. Stronger regulation and supervision aimed at problems with underwriting practices and lenders’ risk management would have been a more effective and surgical approach to constraining the housing bubble than a general increase in interest rates. Moreover, regulators, supervisors, and the private sector could have more effectively addressed building risk concentrations and inadequate risk-management practices without necessarily having had to make a judgment about the sustainability of house price increases.

For my own part, I can’t really do much but repeat my views expressed in the post Is Crony Capitalism Really Returning to America:

Americans should also be taking a hard look at the ultimate consumer friendliness of their financial expectations. They take as a matter of course mortgages that are:

- 30 years in term

- refinancable at little or no charge (usually; this may apply only to GSE mortgages; I don’t know all the rules)

- non-recourse to borrower (there may be exceptions in some states)

- guaranteed by institutions that simply could not operate as a private enterprise without considerably more financing

- Added 2008-3-8: How could I forget? Tax Deductible

And I will add: following the Crash of 1929, margin rules on stock purchases were tightened:

The great stock market crash of 1929 was blamed on rampant speculation, excessive leverage, and inadequate regulatory oversight. The debacle caused a wave of bank and brokerage failures that devastated the US financial system. Investors were left reeling. In order to restore confidence in the securities markets, the Federal government took several steps, including creating the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, separating the banking and securities industry, and giving the Federal Reserve Board the authority to set margin requirements, which it subsequently did through Regulation T [Reg T].

Margin rules have occasionally come under attack, as reported in 1985:

Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker contended last week in a cover letter accompanying a 189-page report that such federal regulations are no longer needed. If they exist at all, he wrote, they should be set by the securities industry. Buying stocks on credit, his study concluded, “has become much less important . . . than it was in the early 1930s.” In 1928 nearly 10% of all stocks were bought on margin; last year only 1.4% were bought that way.

I think most will agree that in order to protect financial stability, the core banking/brokerage system must make a clear distinction between owner and lender by requiring the owner to put up significant capital to take the first loss in the event of adverse moves. So one regulatory change that would be worth seeing is a requirement that every mortgage have – for example – an ultimate loan-to-value ratio of less than 80%.

Thus, on a $500,000 house, the buyer should put up $100,000. I say “should” rather than “must” because I would not support overly-intrusive regulation: if a bank wants to fund the entire $500,000 and call it a loan – they’re quite welcome to. But – and it’s a big but, as the Bishop said to the actress – that $100,000 has to come from somewhere, so making such a loan will require a dollar-for-dollar adjustment to Tier 1 Capital.

Currently, the $500,000 loan would be risk-weighted at 35% to 175,000; maintaining a 10% Tier 1 Capital ratio then requires $17,500 in capital.

With the change as suggested, $400,000 would be treated as a 35% risk-weighted loan, equating to $140,000, requiring $14,000 in capital; but the $100,000 capital would also be required, bringing the total Tier 1 Capital required for the loan to $114,000 – a rather major difference!

In Canada, mortgages extended by a chartered bank with a loan-to-value of greater than 75% 80% must be CMHC insured; this accomplishes the same purpose (since the capital is, effectively, provided by the bottomless pockets of the taxpayer). And we’ll just have to hope that the CMHC gets their calculations right when setting premia!

Update: Last paragraph edited to reflect comment. See also the CMHC premium schedule and a Globe article on Spend-every-Penny’s musings on tightening the rules.

Update: Musing over the part of Slide 6 that I have reproduced can lead to interesting conclusions … primary among them being that, according to the Fed, US real-estate is a screaming buy right now.

Update, 2010-01-04: Don’t count on CMHC getting the premia calculations right! The Canada Small Business Financing Program, which supports the vitally important food and beverage sector by writing Credit Default Swaps, isn’t doing very well:

The program has so far guaranteed about $10 billion in small-business loans issued by banks, credit unions and others since 1999, and collects fees based on the size of the loan.

The revenue paid to Industry Canada was supposed to cover the default claims paid out, but the math has never worked in Ottawa’s favour.

Claims paid out have risen steadily over the decade, and now top $100 million annually, while revenues have consistently lagged, costing taxpayers a net $335 million so far.

Put another way, cost recovery is currently at only about 60 per cent rather than the 100 per cent that was planned, and is in steady decline.

“The gap between claims and fee revenues will continue to exist and most likely expand,” predicts the KPMG report, dated Oct. 30 and obtained by The Canadian Press under the Access to Information Act.

Update, 2010-01-05: Not surprisingly, Taylor doesn’t buy it:

John Taylor, creator of the so-called Taylor rule for guiding monetary policy, disputed Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke’s argument that low interest rates didn’t cause the U.S. housing bubble.

“The evidence is overwhelming that those low interest rates were not only unusually low but they logically were a factor in the housing boom and therefore ultimately the bust,” Taylor, a Stanford University economist, said in an interview today in Atlanta.

Update, 2010-01-08: James Hamilton of Econbrowser joins the consensus – it’s not a matter of either-or:

Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s observations on monetary policy and the housing bubble have received a lot of attention. Like many other commentators (e.g., Arnold Kling, Paul Krugman, and Free Exchange), I agree with Bernanke’s conclusions, but only up to a point.

…

At least with the benefit of hindsight, I would have thought we could agree that the low interest rate targets of 2003-2005 were a mistake, because more stimulus to housing was the last thing the economy needed. This is not to deny that higher resource utilization rates were a possibility at the time. But I see this as one more illustration, to add to a long string of earlier historical examples, that it is possible to ask too much of monetary policy. Even if the unemployment rate is above where you want it to be and above where you expect it eventually to go, trying to bring it down faster by keeping the monetary gas pedal all the way to the floor can sometimes create bigger problems down the road.

The tone of the three references cited in Dr. Hamilton’s first paragraph is similar: ‘Well, sure, there were regulatory mistakes … but there will always be regulatory mistakes.’ While addressing these errors is a Good Thing, one should not forget to address the monetary policy that exacerbated these errors. Let’s not be too much like die-hard communists, claiming that every failure of that paradigm is due to errors of application, rather than fundamental errors of theory.