Assiduous Readers will know I often use the Interesting External Papers section of PrefBlog as my notepad when reviewing the literature for my own purposes. And that is exactly what this post is … not so much for readers’ information, but for mine, when I want to find this stuff again!

The Bank of Canada Review of Spring 2003 contained an essay by David Longworth, Deputy Governor and life-time employee of the Bank, titled Inflation Targeting and Medium Term Planning: Some Simple Rules of Thumb:

Real long-term bond rates typically average slightly above long-term real growth rates.

Footnote: This has tended to be the case in Canada over the last 20 years. Economic theory would suggest that the real rate of return on capital would exceed the real growth rate of the economy. As long as the risk premium on private capital relative to government bonds is not too large, we would also expect that the real yield on government bonds would be slightly higher than the real growth of the economy. All this is strictly true only in a closed economy. In a small open economy, this real interest rate would reflect the world real interest rate, which in turn would reflect the real growth rate of the world economy.

The Congressional Budget Office has published its December 2007 Background Paper: How CBO Projects the Real Rate of Interest on 10-Year Treasury Notes:

This background paper summarizes CBO’s methods for calculating the natural rate of interest and applying it in projections of the real and nominal interest rates on 10-year Treasury notes.

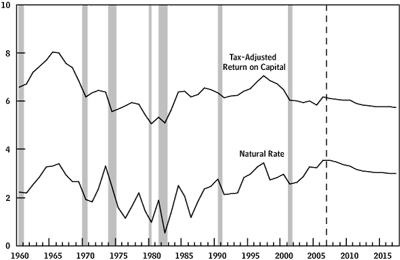

Estimating the natural rate of interest, either over history or for projections, is a two-step procedure. First, CBO estimates the real return on capital (adjusted for taxes on profits). That estimate is based on the agency’s view of the economy’s physical production process—how capital and labor are used to produce output and generate complementary income payments to capital and labor. Because all output simultaneously generates income, data from either the income side or the product (output) side of the national income and product accounts (NIPAs), compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, can be used. Second, CBO estimates an adjustment for the risk in actually realizing the return on capital. Because part of the return on capital is compensation for the risk that some firms will default and inflict losses on investors, an estimate of the real rate based on income payments from capital is higher than the natural rate. Therefore, that risk premium must be removed to yield an estimate of the natural rate. That rate is comparable to the real rate on 10-year Treasury notes, which is also free of default risk. In particular, the risk premium is based on a weighted average of separate estimates of the risk of holding equity and debt claims on capital; it also includes an adjustment for the different tax treatment of profits and interest payments generated by businesses.

Over the next 10 years, CBO projects, the natural rate of interest will decline slightly, from an estimated level of about 3.6 percent in 2006 to about 3 percent. That decline stems from a projected decline in the return on capital, much of which reflects a projected slowdown in the growth of the labor force.

CBO uses two complementary approaches for estimating the return on capital, one from the income side and the other from the product, or production, side.1 The income-based approach measures the rate of return on capital as the ratio of capital income to the capital stock. Its construction has the advantage of being independent of assumptions about production relationships or determinations of whether the economy is in or out of equilibrium. It provides a relatively smooth estimate of the return on capital over the historical and projection periods.

…

The income-side measure is estimated as the ratio of capital income to the capital stock (see Figure 2). Capital income is a domestic private-sector concept estimated as the sum of domestic corporate profits, people’s rental income, 35 percent of proprietors’ income, and interest paid by domestic businesses, using data from the NIPAs2,3 The private-sector capital stock, valued at the prices of newly produced investment goods, consists of businesses’ plant (that is, facilities) and equipment, software, inventories, housing, and land—all valued at current market prices.The income-side measure of the return on capital has both cyclical and trend components. From 1960 to 1970 and from 1991 to 2001, the return rose during the recoveries from recessions and peaked during the expansions, before falling as the expansions matured. Across business cycles, the return has exhibited extended periods in which the underlying trend was falling (as from 1960 to 1980) and then rising (from 1980 to the late 1990s).

…

The estimate of the natural rate of interest is obtained by adjusting the real return on capital (in this instance, the income-side measure) for both tax effects and the combined risk premium (see Figure 7).

Thomas Laubach & John C. Williams, Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest:

A key variable for the conduct of monetary policy is the natural rate of interest – the real interest rate consistent with output equaling potential and stable inflation. Economic theory implies that the natural rate of interest varies over time and depends on the trend growth rate of output. In this paper we apply the Kalman filter to jointly estimate the natural rate of interest, potential output, and the trend growth rate, and examine the empirical relationship between these estimated unobserved series. We find substantial variation in the natural rate of interest over the past four decades in the United States. Our natural rate estimates vary about one-for-one with changes in the trend growth rate. We show that policymakers’ mismeasurement of the natural rate of interest can cause a significant deterioration in macroeconomic stabilization.

FRBSF Economic Letter, 2003-10-31:

Importantly, the natural rate of interest can change, because highly persistent changes in aggregate supply and demand can shift the lines. For example, in a recent paper, Laubach (2003) finds that increases in long-run projections of federal government budget deficits are related to increases in expected long-term real interest rates; in Figure 1, an increase in long-run projected budget deficits would be represented by a rightward shift in the IS curve and a higher natural rate. In addition, economic theory suggests that when the trend growth rate of potential GDP rises, so does the natural rate of interest (see Laubach and Williams (2003) for supporting evidence).

I am not a big fan of the idea that long term interest rates (real or nominal) reflect long term economic growth rates (real or nominal). This can only occur in a completely closed economy — closed to both trade AND capital. The world as a whole might show such a relationship, but the variations between countries are quite enormous.

Look at China, where the economic growth rate is 8-10%. Real interest rates are not this high (maybe 3-4%) and the ROE in Chinese firms was zero for most of the 1990s. The reason: capital importation and positive trade balance increased the investable capital base by way more than returns on investment — allowing the economy to grow faster.

On the other hand, in the US, the long term economic growth rate has been about 3-4%, but (until recently, at least) ROE and sustained returns on investment higher than almost anywhere in the world. I suspect that share buybacks and foreign investment reduced the productive capital base compared with the economy.

As to the debate on real interest rates (e.g. on TIPS). My reading of the 15-year US history of this instrument is that the real interest rate is roughly the same as inflation (i.e. real rates were 4-6% in the early 1990s when inflation was 4-5%, and real rates are now 2% with inflation of 2%). Taxes alone make this reasonable (TIPS very approximately preserve the real value of the investment after taxes), but not every investor is taxable. Also, the nominal bond yield may be proportional to inflation because inflation risk is proportional to inflation.

Back in the 1970’s there was a concern that the real growth rate of the US economy had changed from 4% to 2.5%. From the early 1980s, it actually increased to 3-3.5%. I think major drivers were 1% annual increases in population, greater female participation in the work force, and substantial (computer-assisted?) productivity gains.

Looking forward, population gains are still there, labour force growth is likely to be less (due to demographics of boomer retirement, assuming they can still afford it), and future productivity is unknown. For me, somewhat lower long run growth doesn’t say anything about returns on investment or the “natural interest rate”.