The Bank of England has released the Financial Stability Report, June 2010, stuffed with the usual high-quality research.

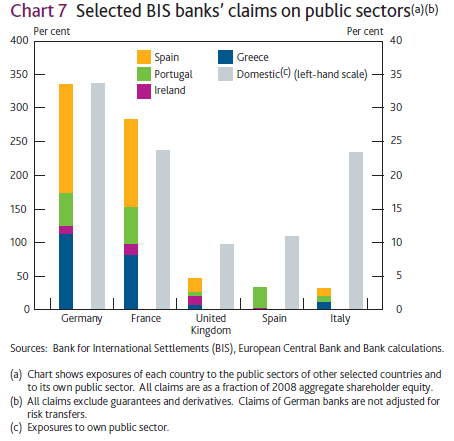

Although UK banks have limited holdings of sovereign debt in economies where fiscal concerns have been most acute (Section 2), they have counterparty relationships with European banking systems that have larger exposures (Chart 7). These banks face further write-downs in 2010, according to the IMF and ECB.

Contingent Capital got an oblique mention:

The Bank welcomes the Government’s establishment of a new independent commission to review the structure of and competition in the UK banking system. Incentives to become [Too Important To Fail] could also be reduced by restrictions on activities and capital surcharges on institutions generating systemic risk. And further measures are needed to ensure that banks’ uninsured creditors face a credible threat of loss. For example, there is international debate about requiring uninsured creditors to recapitalise distressed banks through an extension of the scope of statutory resolution regimes nd through convertible debt instruments.

The Bank of Canada continues to display either its arrogance or ignorance (you pick) by refusing to answer my query regarding Carney’s Ban the Bond speech.

Bless their hearts, they also point out the problem of Central Clearing single point failure, which has been given short shrift in the proposals:

Initiatives are under way to extend central counterparty (CCP) clearing. But this will only improve resilience if appropriate CCP risk management standards are in place (see box on pages 69–70). For example, holding sufficient resources to meet the default of at least the two largest member counterparties — in stressed but plausible market conditions — would help to reduce systemic risks.

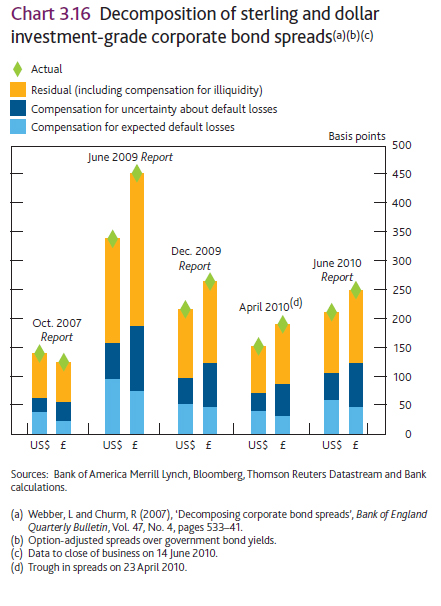

They publish their liquidity calculations again: do not buy a single corporate credit without understanding the implications and rationale behind this chart!

Box 7 contains an interesting discussion of the sadly neglected cost-benefit analysis of higher capital levels:

Estimates from the structural model can be used to compare the marginal benefits and costs of higher capital levels. Chart A shows that marginal costs are roughly linear in the capital ratio. Marginal benefits decline sharply as capital levels rise, reflecting the decreasing likelihood of shocks that are

large enough to cause a bank’s default (Chart B). Confidence intervals around the central estimates (magenta lines) are also shown.(15) Although only illustrative, these estimates suggest marginal costs and benefits are equated at capital ratios between 10% and 15%.

They also focus on the distinction between trading and investing:

The current definition of the regulatory trading book is based on the concept of ‘trading intent’. From a prudential perspective, however, a firm’s intention to trade is less relevant than its ability to trade, which may be constrained by a lack of market liquidity. The current regime is also inconsistent in the treatment of risk either side of the trading/banking book boundary. Broadly, the banking book captures default risk, while the trading book focuses on market risk. And the assumption underlying the trading book regime is that positions can be liquidated or hedged in a short time period.

This treatment of risk renders the framework susceptible to regulatory arbitrage, as banks have an incentive to classify assets as ‘tradable’ in order to benefit from lower capital charges. This arbitrage opportunity was reflected in the accumulation of increasingly large volumes of illiquid credit-related products in banks’ trading books prior to the crisis (Chart 5.5). During the crisis, a large proportion of trading losses were linked to these credit positions (Chart 5.6).

[…] two aspects of corporate bond pricing came to grief during the Panic of 2007 (see chart 3.16 of the BoE FSR of June 2010 and note the amusing little gap in the […]