The Financial Post reports:

Ms. Dickson, head of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, spelled out her case in the Financial Times yesterday. Her comments, along with those yesterday from Royal Bank of Canada chief executive Gordon Nixon, represent the latest attempts by officials to head off new global financial regulations that could be damaging to Canada.

In a Times opinion piece, Ms. Dickson noted proposals to impose a global bank tax or surcharges on “systemically important” banks have not been universally accepted, with Canada leading the way in opposition to a bank tax.

Instead, she suggested a new scheme in which bank debt would be converted into equity in the event lenders run into trouble. This “embedded contingent capital” would apply to all subordinated securities and would be at least equivalent in value to the common equity.

“This would create a notional systemic risk fund within the bank itself — a form of self-insurance prefunded by private investors to protect the solvency of the bank,” she wrote in the Times.

“What would be new is that investors in bank bonds would now have a real incentive to monitor and restrain risky bank behaviour, to avoid heavy losses from conversion to equity.”

The debt-to-equity conversion would be triggered when the regulator is of the opinion that a financial institution is in so much trouble that no other private-sector investor would want to acquire the asset.

It is very odd that Canadians are reading about Canadian bank regulation in a foreign newspaper. I can well imaging that the Financial Times is more commonly found on the breakfast tables of global decision makers than the Financial Post or the Globe and Mail … but I would have expected a major statement of opinion to be laid out in a speech published on OSFI’s website, which could then be accompanied by opinion pieces in foreign publications.

OSFI’s communication strategy, however, has been notoriously contemptuous of Canadians and markets in general for a long time. The same Financial Post article claims:

Some bank CEOs have grown impatient with Ms. Dickson and Jim Flaherty, the Minister of Finance, who have asked lenders to refrain from raising dividends and undertaking acquisitions — unless they are financed by share offerings that keep their capital ratios high — until there is greater certainty about new financial rules.

It would be really nice if there was a published advisory somewhere, so that the market could see exactly what is being said – but selective disclosure is not a problem if the regulators do it, right?

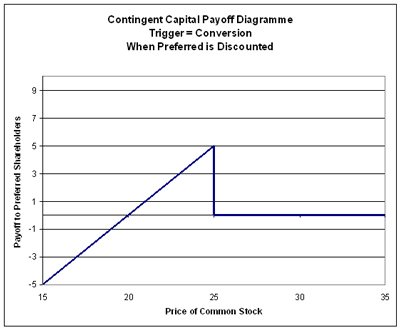

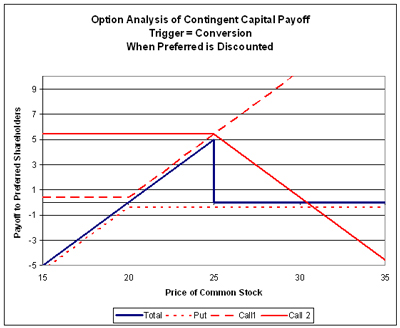

One way or another, I suggest that a regulatory trigger for contingent capital would be a grave mistake. Such a determination by any regulator will be the kiss of death for any institution in serious, but survivable, trouble; therefore, it is almost certain not to be used until it’s too late. Triggers based on the contemporary price of the common relative to the price of the common at the time of issue of the subordinated debt are much preferable, as I have argued in the past.

Ira Stoll of Future of Capitalism quotes the specifics of the piece (unfortunately, I haven’t read the original. Damned if I’m going to pay foreigners to find out what a Canadian bureaucrat is saying) as:

The second question is what triggers the conversion of the contingent capital. She writes, “An identifiable conversion trigger event could be when the regulator is ready to seize control of the institution because problems are so deep that no private buyer would be willing to acquire shares in the bank.”

in which case it is not really contingent capital at all; it’s more “gone concern” capital, without a meaningful difference from the currently extant and sadly wanting subordinated debt. The whole point of “contingent capital” is that it should be able to absorb losses on a going concern basis.

Update: On a related note, I have sent the following inquiry to OSFI:

I note in a Financial Post report(

http://www.nationalpost.com/opinion/columnists/story.html?id=6bb93a4f-b0c0-4d2a-bcd7-be7e6750e212

) the claim that “Despite the low yields, Nagel says the regulatory authorities have given their approval for rate resets to continue to count as Tier 1 capital. But he said the authorities have not been as kind for continued issues of so-called innovative Tier 1 securities.”

Is this an accurate statement of the facts? Has OSFI given guidance on new issue eligibility for Tier 1 Capital, formally or informally, to certain capital market participants that has not been released via an advisory published on your website? If so, what was the nature of this informal guidance?

We will see what, if anything, comes of that.

Update: I have just gained (free!) access to Ms. Dickson’s piece, Protecting banks is best done by market discipline, a disingenuous title if ever there was one. There’s not much detail; but beyond what has already been said:

The conversion trigger would be activated relatively late in the deterioration of a bank’s health, when the value of common equity is minimal. This (together with an appropriate conversion method) should result in the contingent instrument being priced as debt. Being priced as debt is critical as it makes it far more affordable for banks, and therefore has the benefit of minimising the effect on the cost of consumer and business loans.

She does not specify a conversion price, but implies that it will be reasonably close to market:

As an example, consider a bank that issues $40bn of subordinated debt with these embedded conversion features. If the bank took excessive risks to the point where its viability was in doubt and its regulator was ready to take control, the $40bn of subordinated debt would convert to common equity, in a manner that heavily diluted the existing shareholders. While other, temporary measures might also have to be taken to help stabilise the bank in the short run, such capital conversion would significantly replenish the bank’s equity base.

On conversion, the market would be given the message that the bank had been solidly re-capitalised with common equity, and not that it was still in trouble and its common equity had been bolstered only modestly.

I am very dubious about the claimed message to the market, given the conversion trigger. Frankly, this idea doesn’t look like much more than a regulatorially imposed, somewhat prepackaged bankruptcy – which is something the regulators can do already.

At the height of the crisis, how would you have felt about putting new capital into a company – as either debt or equity – that had just undergone such a process?

Update: I will also point out that the more remote the contingent trigger, the less likely it is to be valued properly.

Update, 2010-4-22: Dickson’s essay has been published on the OSFI website.