A reference on VoxEU alerted me to a CEPR study of the European Bond Market that supplies a few nuggets of information.

Spreads quoted on these electronic [indirect retail] platforms can be quite tight: 10 centimes. One of the reasons why banks are willing to post such tight spreads is that they want to attract volume. This provides them with information about what types of bond are in demand, and that information can then be valuable, for example, in the primary market. In addition, in small retail size, orders are unlikely to be motivated by private information about the fundamentals. Hence, spreads need not include an adverse selection component. This is not unlike market skimming strategies followed by some platforms in the equity market in the US.

I must admit, I don’t understand their comparison with market skimming strategies; which may simply be due to my unfamiliarity with technical marketting terms. According to Zhineng Hu of Sichuan University:

When launching a new product, a firm usually can choose between two distinct pricing strategies, i.e. market skimming and market penetration. A market-skimming strategy uses a high price initially to “skim” the market when the market is still developing. The market penetration strategy, in contrast, uses a low price initially to capture a large market share.

It seems to me that a “market skimming” strategy would imply high spreads, while low spreads imply a “market penetration” strategy. Something to ponder …

They have some things to say about the CDS market:

Lack of liquidity in the corporate bond market can arise because i) it is difficult and costly to short bonds, and ii) for each issuer, liquidity can be spread across a large number of bonds. These problems are overcome in the case of the CDS market. Because these are derivative contracts, they enable traders to take short or long position relative to the default risk of an issuer. Also, even if the issuing firm has issued several bonds, a single standardized CDS contract can be used to manage the corresponding default risk. Trading this contract can become a focal equilibrium. Such concentration of trading can increase liquidity and reduce trading costs. Longstaff et al. (2003) offer very interesting empirical evidence on this point. Controlling for credit risk by comparing CDS and underlying bonds, they find that yield spreads are greater in the cash market than in the CDS market. They show that this difference reflects (in part) the greater liquidity of the CDS market.

Ah, the good old days of the positive basis!

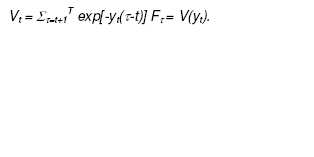

They propose a rather unusual definition of Yield-to-Maturity:

Well, I’ve discussed Yield-to-Maturity until I’m blue in the face … all I will say is that the formula given assumes infinite compounding, which is not how issuers quote their bonds!

Section 4.8.3 shows the real-world effects of over-regulation:

The primary market is regulated by the Prospectus Directive, together with its close counterpart the Transparency Directive, (both of which came into use in 2005), as well as national rules. This directive was designed to protect investors, by enhancing transparency. Firms marketing their bonds to the investor public must issue very complete prospectuses and comply with European accounting standards. This can have some perverse effects: retail investors actually do not read long and complex prospectuses, yet those are very costly to produce. Furthermore, for non European issuers, it can be a great burden to comply with European accounting standards. Some issuers reacted by taking measures that limit their bond sales to retail investors, to avoid the regulation. Thus they set the minimum bond size above € 50,000. This reduces the universe of bonds to which retail investors have access, and it can also be costly for smaller funds.

Canadian retail investors seeking to purchase Maple bonds will be very familiar with the process!

But of most interest was the data on trading frequency … I have been looking for some time for an authoritative reference to use when discussing corporate bond trading frequency!

Trading activity: The average number of trades per bond and per day is slightly above 3 for euro-denominated bonds and 2 for sterling-denominated bonds. For euro-denominated bonds the average transaction size is around one million euros. For sterling-denominated bonds it is around £800,000. Trading activity is relatively stable throughout our sample years.

…

Figure 7 depicts the average daily number of trades for bonds with different ratings. The relation between the average daily number of trades and the rating of the bond is Ushaped, for both currencies. AAA rated bonds and BBB rated bonds are the most frequently traded, while AA and A are somewhat less frequently traded. This could reflect the interaction of two countervailing effects. On the one hand, high rating can increase liquidity by reducing adverse selection. On the other hand, news affecting the values of higher risk bonds is relatively more frequent, thus generating relatively greater activity. Finally note that for both currencies and all ratings, there are no clear differences across years in terms of average number of bonds traded.

…

The European bonds in our sample are more frequently traded than the US corporate bonds analysed by Goldstein, Hotchkiss and Sirri (2005) and Edwards, Harris and Piwowar (2005). Goldstein, Hotchkiss and Sirri (2005), focusing on BBB bonds, find an average number of trades per day equal to 1.1, which is lower than the medians in our sample for BBB bonds in 2003: 4.12 for euros and 2.51 for sterling. Edwards, Harris and Piwowar (2005), study bonds spanning several ratings, and find an average number of trades per day equal to 1.9, again lower than what we find. This is all the more striking since our dataset, in contrast with theirs, does not include the small trades. The latter, although small in terms of total dollar trading volume, account for more than half the number of trades in the TRACE-based studies.