Pembina Pipeline Corporation has announced:

that it has closed its previously announced offering of $225 million aggregate principal amount of 5.95% Fixed-to-Fixed Rate Subordinated Notes, Series 2 (the “Series 2 Notes”) due June 6, 2055 (the “Offering”). The Series 2 Notes were offered through a syndicate of underwriters, co-led by CIBC Capital Markets, BMO Capital Markets and Scotiabank, under Pembina’s short form base shelf prospectus dated December 13, 2023, as supplemented by a prospectus supplement dated October 8, 2025.

As previously announced, Pembina intends to use the net proceeds of the Offering to fund the redemption of all of its outstanding Cumulative Redeemable Rate Reset Class A Preferred Shares, Series 9 (TSX: PPL.PR.I) (the “Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares”) on December 1, 2025 (the “Redemption Date”) at a price equal to $25.00 per Series 9 Class A Preferred Share (the “Redemption Price”), less any tax required to be deducted or withheld by the Company and for general corporate purposes. The aggregate Redemption Price to Pembina will be $225 million.

Pembina previously announced that the dividend payable on December 1, 2025, to the holders of the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares of record on November 3, 2025, will be $0.268875 per Series 9 Class A Preferred Share. This will be the final quarterly dividend on the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares. Upon payment of the December 1, 2025 dividend, there will be no accrued and unpaid dividends on the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares as at the Redemption Date.

The Company has provided notice today of the Redemption Price and the Redemption Date to the sole registered holder of the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares in accordance with the terms of the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares, as set out in the Company’s articles of amalgamation dated October 2, 2017. For non-registered holders of Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares, no further action is required, however, they should contact their broker or other intermediary with any questions regarding the redemption process for the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares in which they hold a beneficial interest. The Company’s transfer agent for the Series 9 Class A Preferred Shares is Computershare Investor Services Inc. Questions regarding the redemption process may also be directed to Computershare at 1-800-564-6253 or by email to corporateactions@computershare.com.

PPL.PR.I was issued as a FixedReset, 4.75%+391, that commenced trading 2015-4-10 after being announced 2015-3-31. It reset to 4.302% effective 2020-12-1 and there was no conversion. It is tracked by HIMIPref™ but relegated to the Scraps index on credit concerns.

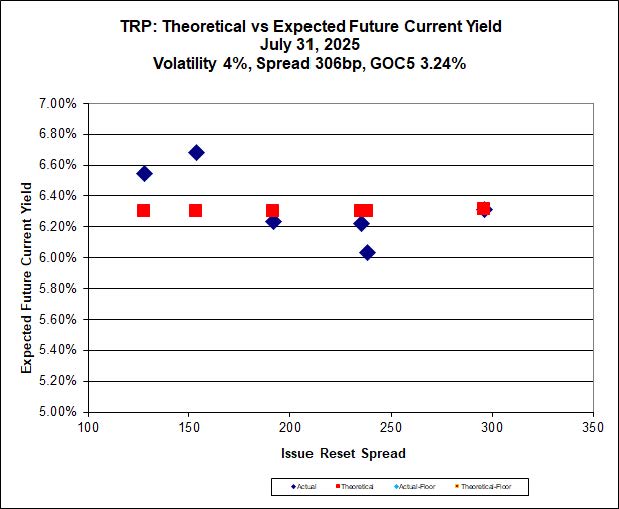

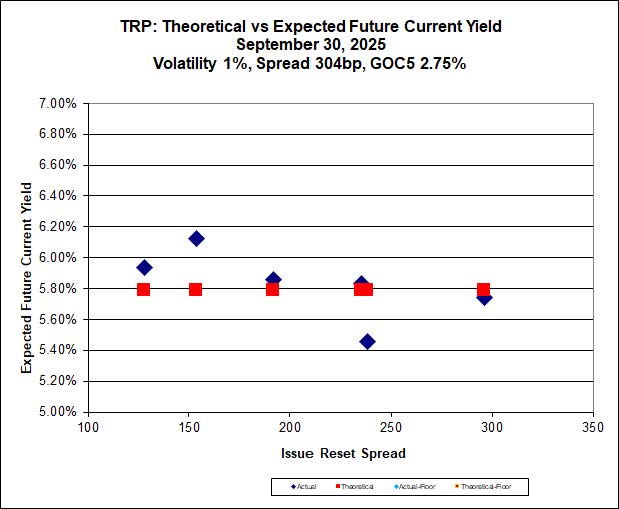

It’s nice to get some more confirmation (after the recent TRP.PR.G refunding) that the Canadian preferred share market continues to be cheap!

Thanks to Assiduous Reader niagara for bringing this to my attention!