The Bank of Canada has released a working paper by Jason Allen, Ali Hortaçsu and Jakub Kastl titled Analyzing Default Risk and Liquidity Demand during a Financial Crisis: The Case of Canada:

This paper explores the reliability of using prices of credit default swap contracts (CDS) as indicators of default probabilities during the 2007/2008 financial crisis. We use data from the Canadian financial system to show that these publicly available risk measures, while indicative of initial problems of the financial system as a whole, do not seem to

correspond to risks implied by the cross-sectional heterogeneity in bank behavior in short-term lending markets. Strategies in, and reliance on the payments system as well as special liquidity-supplying tools provided by the central bank seem to be more important additional indicators of distress of individual banks, or lack thereof than the CDSs. It therefore seems that central banks should utilize high-frequency data on liquidity demand to obtain a better picture of financial health of individual participants of the financial system.

Essentially, the paper provides further evidence that the bond market is excitable:

In contrast to public measures of bank risk (such as CDS prices), which varied widely both crosssectionally and in the time-series, we show that Canadian banks’ bidding behavior in the liquidity auctions as well as their behavior in the payment system and overnight interbank market was largely indicative of low risk. The fact that overnight market remained quite active throughout the crisis – total loans transacted stayed virtually unchanged while prices actually fell – indicates that participants did not believe there were significant liquidity or counterparty risks. Similarly, Afonso, Kovner and Schoar (2010) find that the overnight Feds Fund market remained active following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, although they do find evidence of increased counterparty risk. We argue that the impact of various liquidity-providing actions undertaken by the cental bank and federal government during 2008 might have led to a surplus of liquidity in the market, resulting in overnight unsecured loans transacting even below the target rate. In contrast, we find that during the asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) crisis in the summer of 2007, when these extraordinary liquidity facilities did not exist, interbank rates did increase. Similar to Acharya and Merrouche (2010) this suggests liquidity was more scarce at this time. In neither episode, however, do we find evidence of an increase in counterparty risk.

…

We will provide evidence that in the case of Canadian financial institutions, for which CDS spreads varied substantially both in the cross-section and in the time series, the corresponding variation in the short-term spreads was lacking. We will argue based on further indirect evidence that it therefore seems that in case of fairly illiquid CDS markets, the short term spreads recovered from the bidding behavior in liquidity auctions may provide a more useful source of information about counterparty risk and potential financial trouble in the turbulent times of a crisis.

…

The situation in Canada was remarkably different. While the default probabilities of individual banks implied by the prices of their respective CDS contracts followed a similar pattern as their European counterparts, the Canadian banking system showed very limited signs of stress (or increase in liquidity demand) in 2007 and in the first half of 2008. In particular, the Canadian banks were much less willing to pay a premium above the reference overnight rate to obtain liquidity from the Bank of Canada. Figure 4 depicts the aggregate bidding functions in each auction that the Bank of Canada conducted before September 2008. It suggests that virtually all banks judged that even if they would not have their demands in these auctions satisfied, they could secure the liquidity elsewhere and hence were bidding at, or very close to, the reference overnight rate (OIS).

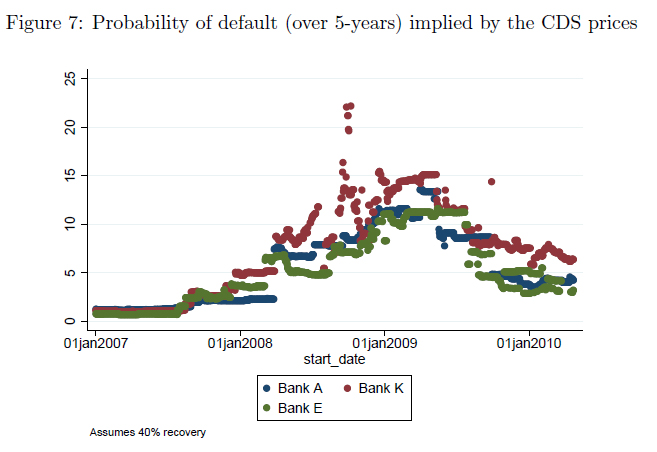

Using the standard

formula (see e.g., Hull (2007)):Pr (Default 5y)T = 100 * (1 – (1/(1 + (cdsT /10000)/(1 – recovery))T ))

we can recover the risk-neutral default probabilities implied by the CDS prices. For the largest institutions, banks A,E and K, the implied default probabilities (assuming 40 per cent recovery rates) went from close to zero to over 15 per cent. Given the increase in default risk implied by the CDS contracts on the banks in our sample we might expect an increase in liquidity hoarding during the crisis.