The Fed has announced:

that it will alter the formulas used to determine the interest rates paid to depository institutions on required reserve balances and excess reserve balances.

Previously, the rate on required reserve balances had been set at the average target federal funds rate established by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) over a reserves maintenance period minus 10 basis points. The rate on excess balances had been set as the lowest federal funds rate target in effect during a reserve maintenance period minus 35 basis points. Under the new formulas, the rate on required reserve balances will be set equal to the average target federal funds rate over the reserve maintenance period. The rate on excess balances will be set equal to the lowest FOMC target rate in effect during the reserve maintenance period. These changes will become effective for the maintenance periods beginning Thursday, November 6.

Econbrowser‘s James Hamilton writes a fine piece on these developments, The new, improved fed funds market, noting wryly:

Yet another week of institutional changes that render all those nice macroeconomic texts and professors’ lecture notes obsolete.

The critical question is:

Why would any bank lend fed funds to another bank at a rate less than 1%, exposing itself to the associated overnight counterparty risk, when it could earn 1% on those same reserves risk free from the Fed just by holding on to them?

… and it may be that the answer is in that mysterious “Other Deposits” line on the Fed’s balance sheet. Dr. Hamilton explains:

Wrightson ICAP (subscription required) proposes that part of the answer is the requirement by the FDIC that banks pay a fee to the FDIC of 75 basis points on fed funds borrowed in exchange for a guarantee from the FDIC that those unsecured loans will be repaid. If you have to pay such a fee to borrow, it’s not worth it to you to pay the GSE any more than 0.25% in an effort to arbitrage between borrowed fed funds and the interest paid by the Fed on excess reserves. Subtract a few more basis points for transactions and broker’s costs, and you get a floor for the fed funds rate somewhere below 25 basis points under the new system.

Dr. Hamilton concludes:

the target itself has become largely irrelevant as an instrument of monetary policy, and discussions of “will the Fed cut further” and the “zero interest rate lower bound” are off the mark. There’s surely no benefit whatever to trying to achieve an even lower value for the effective fed funds rate. On the contrary, what we would really like to see at the moment is an increase in the short-term T-bill rate and traded fed funds rate, the current low rates being symptomatic of a greatly depressed economy, high risk premia, and prospect for deflation.

What we need is some near-term inflation, for which the relevant instrument is not the fed funds rate but instead quantitative expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet. I continue to have concerns about implementing the latter in the form of expansion of excess reserves, which ballooned by another quarter trillion dollars in the week ended November 5. Instead, I would urge the Fed to be buying outstanding long-term U.S. Treasuries and short-term foreign securities outright in unsterilized purchases, with the goal of achieving an expansion of currency held by the public, depreciation of the currency, and arresting the commodity price declines.

Of Dr. Hamilton’s three symptons for low rates, I suggest that “high risk premia” is the dominant force. And thus, perhaps counter-intuitively, I suggest that Fed should have simultaneously raised the required yield on the Commercial Paper Funding Facility by 35bp, to maintain – at the very least – the current spread between what banks can earn at the Fed and the competitive rate of commercial paper. We want the Fed out of the intermediation business!

Before news this week of General Motors’ enormous problems and possible bankruptcy – referenced November 7 – I would have deprecated Dr. Hamilton’s call for massive monetary stimulus. Now … I’m not so sure.

Update, 2008-11-11: Dr. Hamilton has withdrawn his hypothesis that the FDIC guarantee fees are responsible for the difference between the effective fed funds rate and the target rate.

Rebecca Wilder argues that this could not be affecting the current effective fed funds rate due to details of the “opt out” provision. Here I provide some further discussion of this point.

I believe that Rebecca Wilder is correct that I was misinterpreting the FDIC October 16 technical briefing.

The gist of the argument is that the fees don’t start until November 13.

One of the commenters noted Deutsche Bank’s hypothesis, discussed on FT Alphaville:

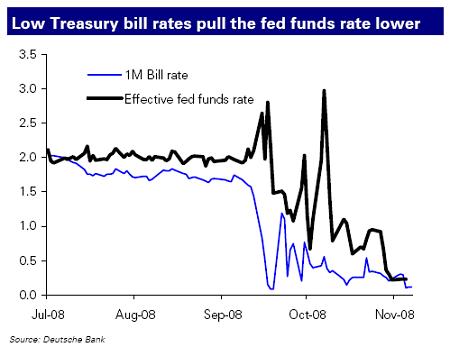

The main reason for this inefficiency has been that Treasury yields are so low that funds leak from the Treasury bill market to the fed funds market. This suppresses the effective funds rate, as investors seek out the higher return until the spread between bills and fed funds compresses. Another reason is that non-banks can participate in the fed funds market, but are excluded from receiving interest on Federal Reserve balances, which are meant for depository institutions… If the agencies supplied these funds to the fed funds market, they would potentially drive the effective fed funds rate lower. Thus monetary policy has been more stimulative than the Fed has intended by setting the target rate, a symptom of an increasing loss of control over monetary conditions.

Rebecca Wilder also makes the supply and demand argument, with two major influences:

First, the huge influx of bank credit increased the reserve base for all banks, and in spite of a surge in excess reserves, the incentive to loan overnight funds grew. This is seen in the second column of the Table; as soon as the credit affecting reserves rose from $31 billion over the year on 9/10 to $275 billion over the year on 9/24, the effective funds rate traded well below its target by an average of 81 bps from 9/10 to 9/24 (the average of the daily spread, or the blue line, in the chart). And no interest was being paid during this period.

Second, as soon as interest was being paid on excess reserves, the GSEs and other banks that hold reserves with the Fed but do not qualify for the new reserve interest payments were forced to offer very low rates in order to sell the overnight funds. The announcement that the Fed would pay interest on reserves (IOR) went into effect on October 9. During that maintenance period, the average spread between the federal funds target and the effective federal funds rate grew to 68 bps. The GSEs forced the market rate downward with the excess supply of reserve balances.

I don’t understand her second point. Interest on Reserves should – and is intended to – boost the demand for reserves, not supply. What may have happened is a supply shock from the GSEs – the latest H.4.1 report shows that “Other” Deposits were $22.8-billion on November 5, an increase of $21.6-billion from October 29 … which is kind of a massive increase!

All this represents a straightforward supply and demand argument. In order for a supply and demand argument to work, we have to dispense with notions of infinite liquidity – we’ve been dispensing with this notion quite a lot in the past year! To nail this down, we have to ask ourselves – why would the big banks not simply bid, say, 90bp for an infinite amount of fed funds and take out a 10bp spread.

One reason might be balance sheet concerns. A borrow is still a borrow and a loan is still a loan, even if both are in the Fed Funds market. A deposit of Fed Funds to the Fed will not attract any risk weight, but will affect the leverage ratio. There may well be reasons for the banks to maintain their leverage ratios as low as possible – even on a daily basis, even with Fed Funds – at the moment.

Another reason might be simply availability of lines. According to the paper Systematic Illiquidity in the Federal Funds Market by Ashcraft & Duffie (Ashcraft’s paper on Understanding the Securitization of Subprime Mortgage Credit has been discussed on PrefBlog):

Two financial institutions can come into contact with each other by various methods in order to negotiate a loan. For example, a federal funds trader at one bank could call a federal funds trader at another bank and ask for quotes. The borrower and lender can also be placed in contact through a broker, although the final amount of a brokered loan is arranged by direct negotiation between the borrowing and lending bank. With our data, described in the next section, we are unable to distinguish which loans were brokered. In aggregate, approximately 27% of the volume of federal funds loans during 2005 were brokered. Based on conversations with market experts, we believe that brokerage of loans is less common among the largest banks, which are the focus of our study.

It should be noted that the authors were required to do a great deal of analysis to determine which FedWire payments were loans and which were other transactions – banks are not required to report their Fed Funds loans and borrows to any central authority. For example, consider this interview on the WSJ:

WSJ: All banks and thrifts qualify for discount window loans. Who participates in the fed funds market?

[Chief economist at Wrightson Associates] Lou Crandall: Almost all banks make use of fed funds transactions, though not necessarily through the brokered market you see quoted on screens. Smaller banks, which typically have surplus funds they want to lend to other banks in the interbank market, will typically often have a correspondent banking relationship with a larger bank, in which the large bank will borrow those funds every day either for its own purposes or to re-sell in the market. Those rolling contracts are booked as fed funds for call report purposes and so forth, but the rates on them aren’t included in the Fed’s effective fed funds rate calculation, which only reflects the brokered market.

This distinction between the “direct” market and the “brokered” market is confirmed by the New York Fed’s definition of the daily effective fed funds rate:

The daily effective federal funds rate is a volume-weighted average of rates on trades arranged by major brokers. The effective rate is calculated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York using data provided by the brokers and is subject to revision.

So when we talk about the Effective Fed Funds Rate, we must bear in mind that we are only talking about brokered transactions – and I will assert that the Ascraft estimate of 27%-brokered is probably much higher than the ratio in the current market.

All this is pretty general, and I don’t have any magic explanations. I will suggest, however, that the immense volume of Fed Funds has simply overwhelmed the operational procedures set up in calmer times; accounts need to be opened, credit limits need to be increased, all the bureaucracy of modern banking has to be brought to bear on the issue before we can again deal with a situation in which liquidity may be approximated to “infinite”.

Update, 2008-11-11: Lou Crandall (or somebody claiming to be him!) has commented on the second Econbrowser post:

Just a quick clarification about FDIC insurance premiums and the fed funds rate. The new 75 basis point insurance premiums won’t go into effect until December, so they are not an explanation for the current low level of the effective funds rate. Our discussion (on the Wrightson ICAP site) of the indeterminacy of the funds rate in that future regime was hypothetical, as we still think there is a chance that the FDIC will choose to exclude overnight fed funds from the unsecured debt guarantee program. As for the current environment, the role of the GSEs and international institutions is in fact a sufficient explanation. Banks have no desire to expand their balance sheets, and so demand a large spread on the transaction before they are willing to accommodate GSEs and others who have surplus funds to dispose of. It’s a specific example of a general phenomenon: the hurdle rate on arbitrage trades has soared due to balance sheet constraints. That fact can be seen everywhere from the spread between the effective fed funds rate and the target in the overnight market to the negative swap spreads in the 20- to 30-year range that have appeared intermittently of late. Finance models that are based on a “no-arbitrage” assumption will need to be shelved, or at least tweaked, for the duration of the financial crisis.

So … he’s saying it’s balance sheet constraints and that it will be a long time until we can return to our comfortable assumptions of infinite liquidity.

2008-11-11, Update #2: This is attracting a lot of attention and Zubin Jelveh of Portfolio.com brings us the views of:

Action Economics’ Mike Englund who argues that there may not actually be one. For example, the average effective rate since the Fed started paying interest on reserves was 0.68 percent. The average excess rate over the same span was 0.70 percent. That’s pretty close and if you look at the last chart again, the market rate does seem to dance around the excess rate until the Fed lowered the target in late-October. Englund tries to explain this last part away:

Note that there is a speculative component to holding excess reserves, as the excess reserve rate for the [reserve maintenance period] RMP is pegged to the “lowest” target in the period, which is not precisely known until the last day of the period. This might explain some “bets” of emergency Fed easing late in the RMP that would lower the excess rate for the entire period, and hence leave a rate that trades through most of the period below the excess reserve “floor.”

I agree with Jelveh … the Englund explanation is not satisfying.

2 comments Fed Funds Developments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] James Hamilton has posted again on the Effective Fed Funds Rate Puzzle – his prior post was discussed on PrefBlog in a post the Professor was kind enough to […]

[…] am happy to see my ‘bureaucracy explanation’ front and […]