The Bank of England has released its June Financial Stability Report filled with the usual tip-top commentary and analysis.

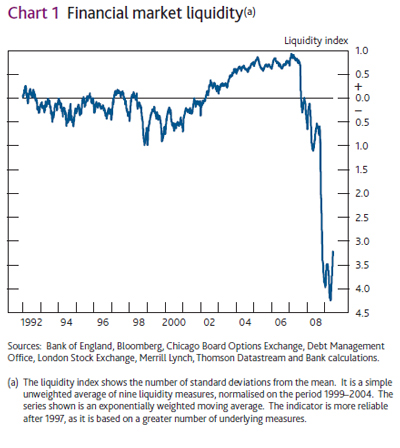

They open with a rather attention-grabbing chart showing their measure of financial market liquidity:

A number of steps towards “greater self insurance” are suggested; most of these a precious boiler-plate, but I was very pleased to see the inclusion of “constant net asset value MMMFs should be regulated as banks or forced to convert to variable net asset funds.” Section 3 fleshes out this idea a little more:

Measures to strengthen regulation and supervision will inevitably also increase avoidance incentives. Left unaddressed, this potentially poses risks for the future. Money market mutual funds (MMMFs) and structured investment vehicles (SIVs) are just two examples from the recent crisis of entities which contributed importantly to the build-up of risk in the financial system, but were not appropriately regulated. By offering to redeem their liabilities at par and effectively on demand, constant net asset value MMMFs in effect offer banking services to investors, without being regulated accordingly. The majority of the global industry comprises US domestic funds, with over US$3 trillion under management. During the crisis, as fears grew that these funds would not be able to redeem liabilities at par — so-called ‘breaking the buck’ — official sector interventions to support MMMFs were required. To guard against a recurrence, such funds need in future either to be regulated as banks or forced to convert into variable net asset value funds.

Footnote: In the United States, the Department of the Treasury has recently announced plans to strengthen the regulatory framework around MMMFs. The Group of Thirty, under Paul Volcker’s chairmanship, has recommended that MMMFs be recognised as special-purpose banks, with appropriate prudential regulation and supervision

They also make the rather breath-taking recommendation that: “The quality of banks’ capital buffers has fallen over time. In the future, capital buffers should comprise only common equity to increase banks’ capacity to absorb losses while remaining operational.” This would imply that Preferred Shares and Innovative Tier 1 Capital would not be included in Tier 1 Capital, if it is included in capital at all! In section 3, they elucidate:

The dilution of capital reduces banks’ ability to absorb losses.

Capital needs to be permanently available to absorb losses and banks should have discretion over the amount and timing of distributions. The only instrument reliably offering these characteristics is common equity. For that reason, the Bank favours a capital ratio defined exclusively in these terms — so-called core Tier 1 capital. This has increasingly been the view taken by market participants during the crisis, which is one reason why a number of global banks have undertaken buybacks and exchanges of hybrid instruments (Box 4).Pre-committed capital insurance instruments and convertible hybrid instruments (debt which can convert to common equity) may also satisfy these characteristics. As such, these instruments could also potentially form an element of a new capital regime, provided banks and the authorities have appropriate discretion over their use. Taken together, these instruments might form part of banks’ contingent capital plans. There is a case for all banks drawing up such plans and regularly satisfying regulators that they can be executed. Subordinated debt should not feature as part of banks’ contingent capital plans, even though it may help to protect depositors in an insolvency.

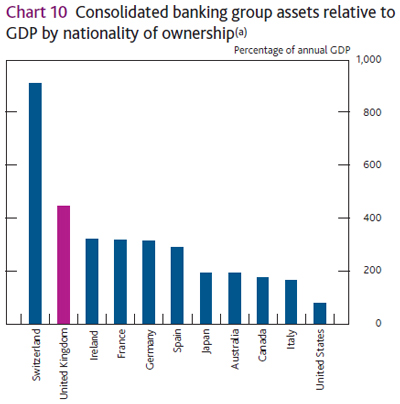

There’s also an interesting chart showing bank assets as a percentage of GDP:

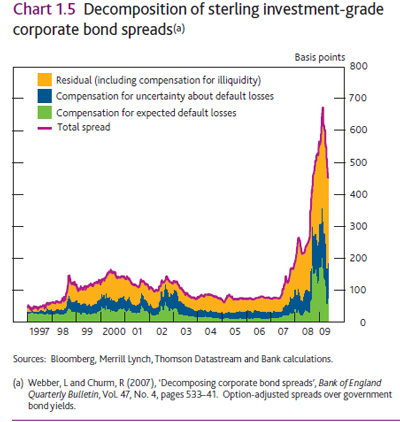

To my pleasure, they updated my favourite graph, the decomposition of corporate bond spreads. I had been under the impression that production of this graph had been halted pending review of the parameterization … wrong again!

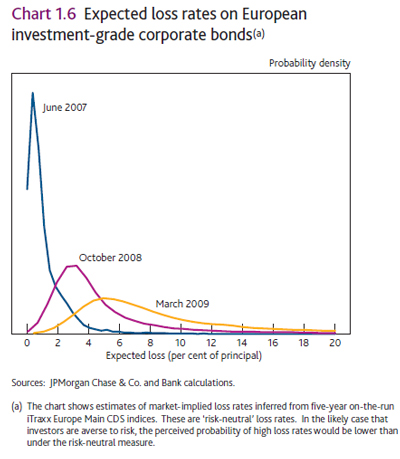

They also show an interesting calculation of expected loss rates derived from CDS index data:

They also recommend a higher degree of risk-based deposit insurance:

Charging higher deposit insurance premia to riskier banks would go some way towards correcting this distortion. These premia should be collected every year, not only following a bank failure, so that risky banks incur the cost at the time when they are taking on the risk. That would also allow a deposit insurance fund to be built up. This could be used, as in the United States and other jurisdictions, to meet the costs of bank resolutions. It would also reduce the procyclicality of a pay-as-you-go deposit insurance scheme, which places greatest pressures on banks’ finances when they can least afford it. For these reasons, the Bank favours a pre-funded, risk-based deposit insurance scheme.

Canada has a pseudo-risk-based system; there are certainly tiers of defined risks, but the CDIC is proud of the fact that, basically, everybody fits into the bottom rung. The CDIC is also pre-funded (in theory) but the level of pre-funding is simply another feel-good joke.

[…] Oddly, they have a chart decomposing credit spreads according to the BoC methodology, which I dislike, as opposed to the Webber & Churm methodology used in the past: […]

[…] I feel compelled to republish one of my favourite graphs, previously shown in the post BoE Releases June 2009 Financial Stability Report: […]