I will admit that I’m very unfamiliar with the Australian bank market, but the Reserve Bank of Australia has released its September 2009 Financial Stability Review:

A number of interrelated factors have contributed to the relatively strong performance of the Australian banking system in the face of the challenges of the past couple of years. One is that Australian banks typically entered the financial turmoil with only limited direct exposures to the types of securities – such as CDOs and US sub-prime RMBS – that led to losses for many banks abroad. Moreover, they have typically not relied on the income streams most affected by recent market conditions: trading income only accounted for around 5 per cent of the major banks’ total income prior to the turmoil. Banks’ wealth management operations have been affected by market developments, but the major banks still reported net income of around $2.3 billion from these activities in the latest half year.

One reason why Australian banks garnered a relatively low share of their income from trading and securities holdings is that they did not have as much incentive as many banks around the world to seek out higher-yielding, but higher-risk, offshore assets. In turn, this was partly because they were earning solid profits from lending to domestic borrowers, and already required offshore funding for these activities. As a result, Australian banks’ balance sheets are heavily weighted towards domestic loans, particularly to the historically low-risk household sector.

As discussed in detail in the previous Review, there are several factors that have contributed to the relatively strong outcome in Australia, including:

- • Lending standards were not eased to the same extent as elsewhere. For example, riskier types of mortgages, such as non-conforming and negative amortisation loans, that became common in the United States, were not features of Australian banks’ lending.

- • The level of interest rates in Australia did not reach the very low levels that had made it temporarily possible for many borrowers with limited repayment ability to obtain loans, as in some other countries.

- • All Australian mortgages are ‘full recourse’ following a court repossession action, and households generally understand that they cannot just hand in the keys to the lender to extinguish the debt.

- • The legal environment in Australia places a stronger obligation on lenders to make responsible lending decisions than is the case in the United States.

- • The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has been relatively proactive in its approach to prudential supervision, conducting several stress tests of ADIs’ housing loan portfolios and strengthening the capital requirements for higher-risk housing loans.

The Australian housing stress-tests of 2003 have been discussed on PrefBlog.

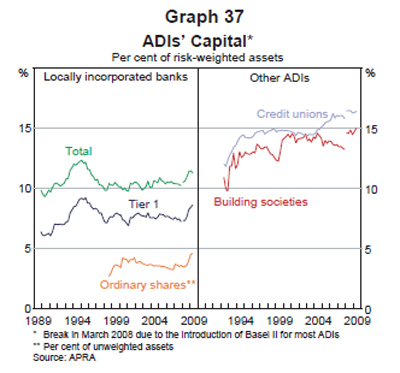

Capitalization is also good:

The Australian banking system remains soundly capitalised.The sector’s Tier 1 capital ratio rose by 1.3 percentage points over the 12 months to June 2009 to 8.6 per cent, its highest level in over a decade (Graph 37). In contrast, the Tier 2 capital ratio has fallen by around 0.7 percentage points over the same period, mainly because term subordinated debt declined. As a result of these developments, the banking system’s total capital ratio has risen by almost 0.7 percentage points over the past year, to stand at 11.3 per cent as at June 2009. A similar pattern has been evident in a simpler measure of leverage – the ratio of ordinary shares to (unweighted) assets – which has risen by around half a percentage point over the past six months. The credit union and building society sectors are also well capitalised, with aggregate total capital ratios of 16.4 per cent and 15 per cent.

In response to falling profits, many banks have cut their dividends (Graph 39). Despite these lower dividends, the major banks’ dividend payout ratio increased to around 80 per cent over the past year.

Most banks are endeavouring to increase their share of funding from deposits, in response to markets’ increased focus on funding liquidity risk. For some of the smaller banks, it is also because of a lack of alternative funding options, given the difficulties in the securitisation market. These factors have led to strong competition for deposits, especially for term deposits, and deposit spreads have widened. For instance, the average rate paid by the major banks on their term deposit ‘specials’ is currentlyaround 175 basis points above the 90-day bank bill rate, compared to about 75 basis points as at end December 2008.

I’m not sure just what a “special” might be … can any Australians elucidate the matter? I assume that a “bank bill” is essentially a bearer deposit note, but confirmation would be appreciated.

After the review of the current environment, there is a discussion of The International Regulatory Agenda and Australia:

As noted in The Australian Financial System chapter, following the capital raisings by the Australian banks this year, the Tier 1 capital ratio for the banking system is at its highest level in over a decade. In addition, APRA’s existing prudential standard requires that the highest form of capital (such as ordinary shares and retained earnings) must account for at least 75 per cent of Tier 1 capital (net of deductions); other components, such as non-cumulative preference shares, are limited to a maximum of 25 per cent. In some other countries this split has been closer to 50:50.

The old Canadian standard was 75%; after relaxing to 70% in January 2008, OSFI debased capital quality requirements in November 2008 to 60%.

“Specials” are teaser rates for new customers. They pay better rates to initially attract retail customers, then hope they get lazy and roll the 3-month deposit at a lower rate.

“Bank Bill Swap Rates” are the market yields on bank paper – it’s used as a benchmark for floating rate, so essentially a LIBOR equivalent.

The other thing they don’t mention is that floating rate funding is much more common over here. For instance the overwhelming majority of Australian listed hybrids (generally not prefs but a note stapled to a pref, but whatever) are floating rate. Residential mortgages are vast majority floating rate. This helps turn the economy quickly – when the RBA moves cash rates *everything* moves in a hurry, there’s no need to refinance for things to flow through into the broader economy.

I talked to a very senior member of one of our big four banks – her view was that a lot of it was luck. They just could not quite bring themselves to lending out lots of low doc or subprime. I got the feeling not that they were planning for crisis, more that they had an attitude that higher risk lending had a kind of moral stain attached. The government’s prevented takeovers and mergers in the big banks as a matter of policy, so competition is mild – this prevented a “race for the bottom” in lending.

Also we had a massive blowup in 1992 with lots of banks going to the wall through dopey lending and internal controls, and one of the majors got terribly mismanaged in the early 2000s – the institutional memory is still fresh.

Thanks, patc and welcome to the board!

I am becoming convinced that Congress caused the crash. With agency paper trading at a minimal premium over treasuries, American banks had to – and have to – extend themselves further out into the risk spectrum than their global peers in order to make any money.

[…] is no acknowledgement of other answers to the question either here or by comparison with Australia. However, given the quality of Canada’s governance, it doesn’t need to be particularly […]