The Bank of Canada has released the Financial Stability Review for December 2011 with articles:

- Risk Assessment

- Macrofinancial Conditions

- Key Risks

- Global Sovereign Debt

- Economic Downturn in Advanced Economies

- Global Imbalances

- Low Interest Rate Environment in Major Advanced Economies

- Canadian Household Finances

- Safeguarding Financial Stability

- Strengthening Bank Management of Liquidity Risk:

The Basel III Liquidity Standards - A Fundamental Review of Capital Charges Associated

with Trading Activities

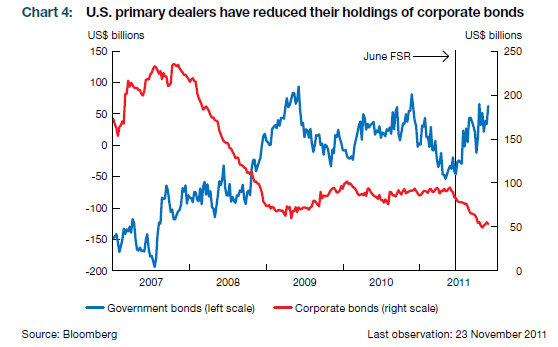

Market-making activity has decreased, with U.S. primary-dealer inventories of corporate bonds falling in recent months (Chart 4).

It remains to be seen whether this is a normal reaction to the ebb and flow of trading activity, or whether the Volcker Rule – and all the other rules that have been introduced in the past few years – have permanently damaged corporate bond market liquidity.

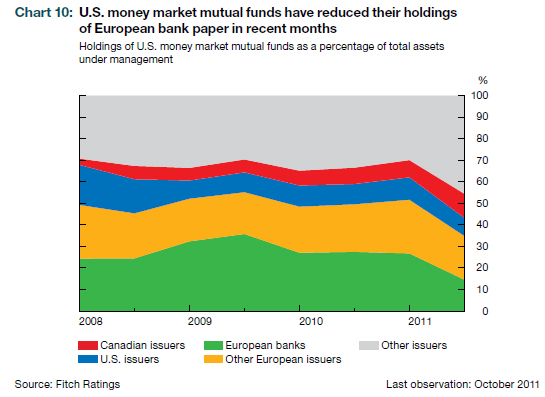

European banks’ access to U.S.-dollar funding has again come under mounting pressure, motivating the ECB to enhance its program to provide U.S.-dollar liquidity. Since European banks hold large amounts of assets denominated in that currency, they have a significant and persistent need for U.S.-dollar funding. This was heightened in recent months as U.S. money market mutual funds reduced their positions in European bank debt (Chart 10), shortened the maturities of their loans to euro-area banks and placed limits on overall counterparty credit exposure. In September, the ECB announced three 3-month U.S.-dollar liquidity operations, allowing financial institutions to secure financing in U.S. dollars beyond the year-end, which is typically a period when funding needs rise owing to seasonal factors. In addition, 1-week U.S.-dollar liquidity operations, which were set to expire in August 2011, have been extended until August 2012.

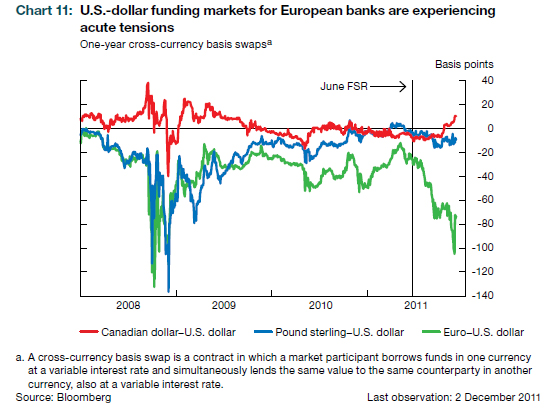

With tensions in U.S.-dollar funding markets particularly acute as a result of rising counterparty concerns in Europe (Chart 11), a group of six central banks, including the Bank of Canada, took action on 30 November to extend U.S.-dollar swap lines with the U.S. Federal Reserve to 1 February 2013. The rate was lowered by 50 basis points, and the network of swap lines was expanded to include bilateral swaps among all pairs of currencies to provide financing if needed. For a number of the central banks involved, including

the Bank of Canada, the U.S.-dollar swap lines have been precautionary in nature, but the ECB has made use of its swap facility to provide U.S.-dollar financing to European banks.

So, obviously, if your requirements are killing you, the best thing to do is reduce your requirements, right? That’s what has the Canadian banks salivating:

This deleveraging is likely to be accelerated by the requirement to boost core Tier 1 capital to 9 per cent of risk-weighted assets by mid-2012, which was announced as part of the 26 October package of measures. Given market conditions, it seems likely that the higher capital ratios will be achieved at least in part through asset sales, as well as retained earnings and capital issuance. In an extreme scenario where only asset sales are used, up to €2.5 trillion of disposals would be required to raise core Tier 1 capital ratios to 9 per cent by next June as agreed to by euro-area leaders. Based on last year’s earnings, and assuming that no dividends are paid, the lower bound for asset sales would be €1.4 trillion.

Asset sales are likely to be concentrated in non-core business lines. For instance, there are reports that European banks have been selling assets in emerging-market economies.

…

Some European banks are also selling U.S.-dollar assets, which has the advantage of reducing the funding-currency

mismatch that has plagued them for the past several years.With recent quarterly results, banks have also announced a number of cost-cutting measures, including downsizing trading desks and other capital market operations. This raises the possibility of a marked decrease in their market-making activities, especially since this appears to be a strategy being used by many banks in Europe and abroad.

Somewhat surprisingly, the FSR points out that the Europeans might have shot themselves in the foot:

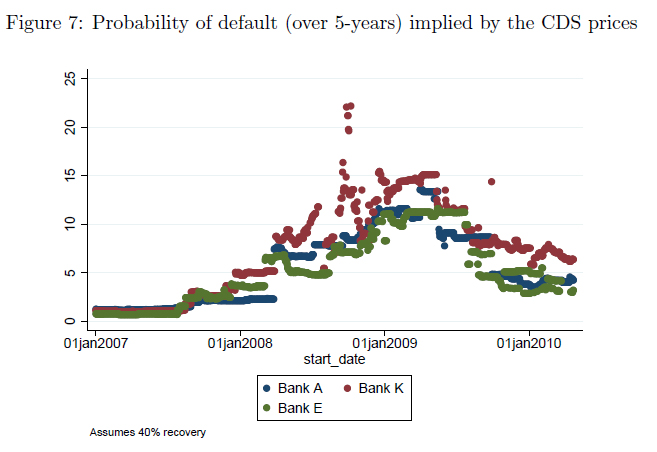

Positions in credit default swap (CDS) markets are used to hedge sovereign risk exposures. Since a credit event triggering payments on sovereign CDSs would entail losses for institutions that have sold credit protection, there is a risk that this could be an important channel of contagion to other markets and institutions. At the same time, the usefulness of such protection is called into question by recent proposals for voluntary writedowns of Greek sovereign debt by 50 per cent without triggering a credit event. The resulting inability to hedge exposures to sovereign credit risk could further reduce investor demand for these securities.

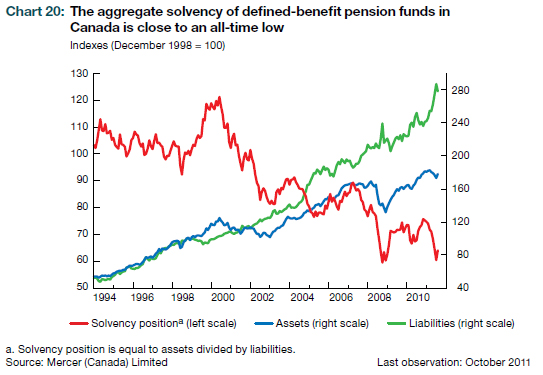

Cheery news for pensioners:

… and for those (ahem!) with high exposure to insurers:

Recent market developments have had a similar negative impact on the life insurance sector. Some large Canadian insurers reported sizable losses in

the third quarter, reflecting the impact of lower interest rates, the decline in equity markets and revisions to actuarial assumptions. The recent market turmoil has also intensified sensitivities to market risk. Equity hedging strategies designed to help mitigate the impact on profit and loss will be less effective under very stressful financial market conditions to the extent that these strategies may be subject to basis and counterparty risk. These issues are especially challenging for firms that have been more aggressive in providing guarantees on investment products and in operating with greater asset-liability mismatches.

To my disappointment, the article by Grahame Johnson on capital charges in the trading book glosses over what I consider to have been the most egregious, and most easily fixed, element of regulatory failure in the run-up to the Panic of 2007: the fact that regulators do not impose a surcharge on trading book positions based on the age of those positions:

Drawing the boundary between the trading book and the banking book on the basis of intent has proven to be vulnerable to misuse. Trading intent is extremely difficult

either to define or to enforce; as such, there is a risk that some assets that might not be readily tradable (or hedgeable) will be held in the trading book. As well, there is a potential for regulatory arbitrage, where firms move positions into whatever classification provides the most favourable capital treatment.This incentive to move positions can work in both directions. For example, credit exposures generally require a lower amount of capital if held in the trading book (given the use of internal models that allow for the benefits of hedging). This provides a strong motivation to securitize credit and hold it in the trading book, even if it is ultimately impossible to sell the exposure. The banking book, on the other hand, does not require assets to be marked to market, which would allow institutions to avoid recognizing (temporary) losses. For securities that have seen sharp declines in market price (which the bank views as temporary), there is an incentive to move these positions to the banking book, where the short-term loss would not have to be recognized. Highly rated sovereign government bonds present an example of this second arbitrage opportunity. In a volatile market, a portfolio of high-grade sovereign bonds could require a significant capital charge in the trading book (based on movements in the market price of the bonds); yet if the holding was moved to the banking book, the securities would have a risk weight of zero and would therefore require no capital.

In addition, long term readers will remember that I also advocate a certain separation of function: banks should declare whether they are primarily traders or primarily bankers, and face a surcharge on their capital requirements for their secondary function.