The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has released Staff Report #449 by Adam Ashcraft, Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham and James Vickery titled MBS Ratings and the Mortgage Credit Boom:

We study credit ratings on subprime and Alt-A mortgage-backed-securities (MBS) deals issued between 2001 and 2007, the period leading up to the subprime crisis. The fraction of highly rated securities in each deal is decreasing in mortgage credit risk (measured either ex ante or ex post), suggesting that ratings contain useful information for investors. However, we also find evidence of significant time variation in risk-adjusted credit ratings, including a progressive decline in standards around the MBS market peak between the start of 2005 and mid-2007. Conditional on initial ratings, we observe underperformance (high mortgage defaults and losses and large rating downgrades) among deals with observably higher risk mortgages based on a simple ex ante model and deals with a high fraction of opaque lowdocumentation loans. These findings hold over the entire sample period, not just for deal cohorts most affected by the crisis.

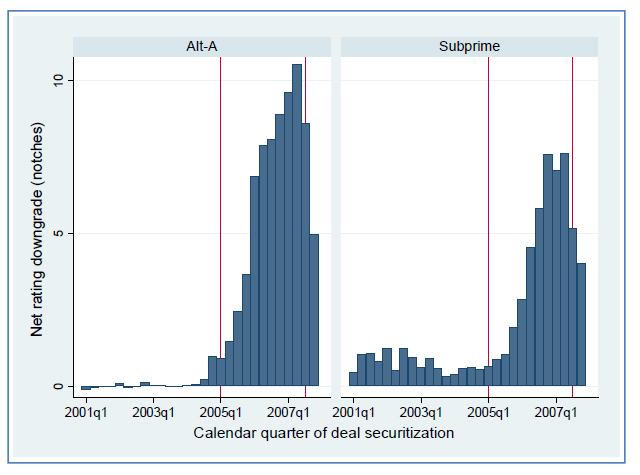

Figure plots average net nonprime MBS ratings revisions by calendar quarter of deal issuance. Covers subprime and Alt-A deals in our sample issued between Q1:2001 and Q4:2007. Y-axis measures the average net number of rating notches that securities issued in calendar quarter have been downgraded between issuance and August 2009, weighted by security original face value.

Figure 1 plots net rating revisions on subprime and Alt-A MBS issued since 2001. While net rating revisions are small for earlier vintages, MBS issued since 2005 have experienced historically large downgrades, by 3-10 rating notches on average, depending on the vintage. Critics interpret these facts as evidence of important flaws in the credit rating process, either due to incentive problems associated with the “issuer-pays” rating model, or simply insufficient diligence or competence (e.g. US Senate, 2010; White, 2009; Fons, 2008).1 In their defense however, rating agencies argue that recent MBS performance primarily reflects a set of large, unexpected shocks, including an unprecedented decline in home prices, and a financial crisis, events which surprised most market participants.

They look at the problem of relative risk:

The second part of our analysis examines how well credit ratings order relative risks across MBS deals from within a given cohort. Here we focus on studying variation in realized performance. If credit ratings are informative, mortgages underlying deals rated more optimistically (i.e. lower subordination, or equivalently a larger fraction of highly-rated securities), should perform better expost, in terms of lower mortgage default and loss rates. Furthermore, prior information available when the deal was initially rated should not be expected to systematically predict deal performance, after controlling for credit ratings. This is because this prior information should already be reflected in the ratings themselves, to the extent it is informative about default risk.

I strongly disagree with their assertions in thelast two sentences, which is simply a variation on the Efficient Market Hypothesis. As I have repeatedly stressed, financial markets represent a chaotic system, which is a system in which various factors leading to the result can interact in unusual ways – a small difference at time 0 can eventually be shown to lead to an enormous difference at time t.

If I work for a garden center and predict fine planting weather for the following weekend – which turns out to be disastrously wrong – the discovery that I neglected to account for a butterfly flapping its wings in China an extra time does not make me incompetent and does not prove that the conflict of interest presented by the nature of my employment corrupted my obectivity. Either conclusion could be true, but require a lot more proof than the premises stated.

Mind you, the authors’ data is much more obviously relevant to the problem than in the garden-centre scenario:

We find higher subordination is generally correlated with worse ex-post mortgage performance, as expected. However, conditional on subordination, time dummies and credit enhancement features, we also find significant variation in performance across different types of deals. First, MBS deals backed by loans with observably risky characteristics such as low FICO scores and high leverage (summarized by the projected default rate from our simple ex-ante model) perform poorly relative to initial subordination levels. Moreover, deals with a high share of low- and no-documentation loans (“low doc”), perform disproportionately poorly, even relative to other types of observably risky deals. This suggests such deals were not rated conservatively enough ex-ante.

Importantly, they show that these correlations are robust throughout the period of interest:

These findings hold robustly across several different measures of deal performance: (i) early-payment defaults; (ii) rating downgrades; (iii) cumulative losses; (iv) cumulative defaults. In some cases, our results are magnified for deals issued during the period of peak MBS issuance from the start of 2005 to mid-2007. However, perhaps most notably, we repeat our analysis separately for each annual deal cohort between 2001 and 2007. We find that the underperformance of low-doc and observably high risk deals holds surprisingly robustly over the entire sample period, including earlier deal vintages not significantly affected by the crisis. Indeed, these differences in performance can be observed even only based on performance data publicly available before the crisis starts.

This is an important test, but still does not prove incompetence or corruption. It is important to consider what information was available during the peak period – had these correlations shown up at that time? They address this question in the section “Loan Level Model”:

While we are careful to estimate the model parameters only using prior available data, a “look-back” bias may also arise if our choice of explanatory variables or model structure is influenced by knowledge of the evolution of the crisis. To minimize these concerns, we deliberately choose a simple model structure (a basic logit), and consider only explanatory variables that CRAs also used in the rating process. For example, Moody’s (2003) description of their primary subprime ratings model lists as inputs all the main variables included in our default model specification.8 We emphasize that this default model is intentionally simple, to avoid look-back biases, and in several respects is less complex than the models used by rating agencies themselves.9 Any shortcomings of our model lower the benchmark against which credit ratings are compared as a predictor of deal performance (see Section 7 for further discussion).

The literature review is CRA-hostile, ranging from the trivial:

Bolton et al. (2008) assume each CRA has a private signal of the quality of a security to be rated, which can be either reported truthfully or misreported. Misreporting leads to an exogenous reputation cost if detected, but generates higher fee income from security issuers in the current period. Bolton et al show ratings inflation is more severe when reputation costs are low relative to current rating profits, suggesting CRAs are more likely to misreport risk during booms.

… to the more interesting:

Turning to structured finance ratings, Benmelech and Dlugosz (2010) document the wave of recent downgrades across different types of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). They find evidence that securities rated by only one CRA are downgraded more frequently, which is interpreted as evidence of rating shopping. Griffin and Tang (2009) find that published CDO ratings by a CRA are less accurate than the direct output of that CRA’s internal model, suggesting judgmental adjustments were applied to model-generated ratings that worsened rating quality. Coval, Jurek and Stafford (2009) show default probabilities for structured finance bonds are very sensitive to correlation assumptions. Studying MBS, He, Qian and Strahan (2009) present evidence that large security issuers receive more generous ratings, particularly for securities issued from 2004-06. (Unlike this paper, however, these authors are not able to control for information on deal structure or underlying mortgage collateral). Cohen (2010) finds evidence that measures of rating shopping incentives, such as the market share of each CRA, affects commercial MBS subordination.

…

Kisgen and Strahan (2009) present evidence that ratings influence prices through their role in financial regulation. They show the certification of DBRS by the SEC shifts prices in the direction of their DBRS rating amongst bonds already rated by DBRS. Adelino (2009) finds performance of junior triple-A MBS bonds is uncorrelated with initial prices, suggesting triple-A investors relied excessively on credit ratings, rather than conducting due diligence. Chernenko and Sunderam (2009) find ratings variation around the investment grade boundary creates market segmentation that affects credit supply and firm investment.

It is interesting to contrast Kisgen and Strahan’s point with the prior adoration of the Efficient Market Hypothesis!

The authors conclude in part:

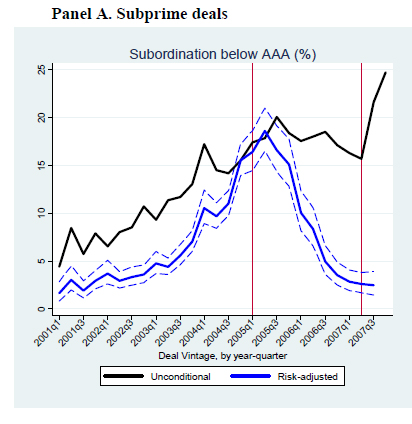

Our evidence does suggest that ratings are informative, and also rejects a simple story that credit rating standards deteriorate uniformly over the pre-crisis period. However, we find evidence of apparently significant time-series variation in subordination levels; most robustly, we observe a significant decline in risk-adjusted subordination levels between the start of 2005 and mid-2007.

Our analysis also suggests MBS ratings did not fully reflect publicly available data. Observably high-risk deals, measured by a simple ex-ante model, significantly underperform relative to their initial subordination levels. Deals with a high share of low-documentation mortgages also perform disproportionately worse compared to other types of risky deals. These two results are evident even for earlier vintages, and can be identified even only using pre-crisis data.

Our results are not conclusive about the role of explicit agency frictions in the rating process. However, two of our results appear consistent with recent theoretical literature modeling these frictions: (i) the poor performance relative to ratings of deals backed by opaque low-documentation loans, and (ii) the observed decline in risk-adjusted subordination around the peak of MBS issuance, when incentive problems are likely most severe. Further analysis of the importance of explicit rating shopping and other incentive problems is, we believe, an important topic for future research.

Click for Big

[The above chart presents] conditional and risk-adjusted AAA subordination for subprime and Alt-A deals, respectively. Risk-adjusted subordination reflects residual changes in credit ratings after controlling for the variables in Table 5 (such as the model-projected default rate, insurance dummy etc.)