The SEC & CFTC have released the FINDINGS REGARDING THE MARKET EVENTS OF MAY 6, 2010:

At 2:32 p.m., against this backdrop of unusually high volatility and thinning liquidity, a large fundamental5 trader (a mutual fund complex) initiated a sell program to sell a total of 75,000 E-Mini contracts (valued at approximately $4.1 billion) as a hedge to an existing equity position.

…

This large fundamental trader chose to execute this sell program via an automated execution algorithm (“Sell Algorithm”) that was programmed to feed orders into the June 2010 E-Mini market to target an execution rate set to 9% of the trading volume calculated over the previous minute, but without regard to price or time.

As noted by Bloomberg, the identity of the seller is no mystery:

While the report doesn’t name the seller, two people with knowledge of the findings said it was Waddell & Reed Financial Inc. The mutual-fund company’s action may not have caused a crash if there weren’t already concern in the market about the European debt crisis, the people said.

“When you don’t put a limit price on orders, that’s what can happen,” said Paul Zubulake, senior analyst at Boston-based research firm Aite Group LLC. “This is not a manipulation or an algorithm that ran amok. It was told to be aggressive and not use a price. The market-making community actually absorbed a lot of the selling, but then they had to hedge their own risk.”

According to a recent press release:

At June 30, 2010, the company had approximately $68 billion in total assets under management.

So my questions for Waddel Reed are:

- Why is the sale of $4.1-bilion (about 6% of AUM) in securities a binary decision?

- Why are you putting in market orders for $4.1-billion?

- Is there anybody there with any brains at all?

So this is simply the old market-impact costs rigamarole writ large: Bozo Trader wakes up one morning, finds his big toe hurts and concludes that he should sell X and buy Y. At the market! No further analysis needed.

Back to the report. Amusingly:

However, on May 6, when markets were already under stress, the Sell Algorithm chosen by the large trader to only target trading volume, and neither price nor time, executed the sell program extremely rapidly in just 20 minutes.(footnote)

Footnote: At a later date, the large fundamental trader executed trades over the course of more than 6 hours to offset the net short position accumulated on May 6.

I guess his big toe wasn’t hurting the following week. Still, from a market perspective, I think it’s pretty impressive that the market was able to absorb that much selling while limiting the market impact to what was actually experienced.

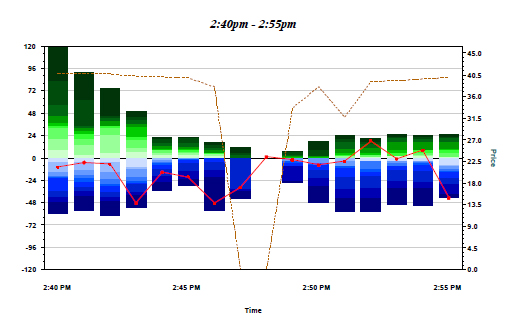

HFTs and intermediaries were the likely buyers of the initial batch of orders submitted by the Sell Algorithm, and, as a result, these buyers built up temporary long positions. Specifically, HFTs accumulated a net long position of about 3,300 contracts. However, between 2:41 p.m. and 2:44 p.m., HFTs aggressively sold about 2,000 E-Mini contracts in order to reduce their temporary long positions. At the same time, HFTs traded nearly 140,000 E-Mini contracts or over 33% of the total trading volume. This is consistent with the HFTs’ typical practice of trading a very large number of contracts, but not accumulating an aggregate inventory beyond three to four thousand contracts in either direction.

The Sell Algorithm used by the large trader responded to the increased volume by increasing the rate at which it was feeding the orders into the market, even though orders that it already sent to the market were arguably not yet fully absorbed by fundamental buyers or cross-market arbitrageurs. In fact, especially in times of significant volatility, high trading volume is not necessarily a reliable indicator of market liquidity.

3,300 contracts is about $180-million. So now we know how much money the HFT guys are prepared to risk.

Still lacking sufficient demand from fundamental buyers or cross-market arbitrageurs, HFTs began to quickly buy and then resell contracts to each other – generating a “hot-potato” volume effect as the same positions were rapidly passed back and forth. Between 2:45:13 and 2:45:27, HFTs traded over 27,000 contracts, which accounted for about 49 percent of the total trading volume, while buying only about 200 additional contracts net.

At this time, buy-side market depth in the E-Mini fell to about $58 million, less than 1% of its depth from that morning’s level.

So they’re saying that total depth in the morning was $5.8-billion, but it is certainly possible that a lot of that was duplicates. There is not necessarily a high correlation between the amount of bids you have on the table and the amount of money you’re prepared to risk: you might intend on pulling some orders as others get filled, or immediately hedging your exposure as each order is executed in turn.

[Further explanation added 2010-10-2: For instance, we might have two preferred share issues trading, A & B, both quoted at 23.00-20. I want to sell A and buy B, but since I have a functioning brain cell I want to do this at a fixed spread. For purposes of this example, I want to execute the swap as long as I can do both sides at the same price. I don’t care much what that price is.

What I might do is enter an offer on A at 23.20 and a bid on B at 23.00. If one side of the order is executed, I will then change the price of the other. If things work out right, I’ll get a bit of my trade done. It could be that only one side of the trade will execute and the other won’t – that’s simply part of the risks of trading and that’s what I get paid to judge and control: if I get it right often enough, my clients will make more money than they would otherwise.

The point is that my bid on B is contingent. If the quote on A moves, I’m going to move my bid on B. If the market gets so wild that I judge that I can’t count on executing either side at a good price after the first side is executed, I’m going to pull the whole thing and wait until things have settled down. I do not want to change my total exposure to the preferred share market, I only want to swap within it.

Therefore, you can not necessarily look at the order book of B, see my bid order there, and conclude that it’s irrevocably part of the depth that will prevent big market moves.

Once you start to become suspicious that you cannot, in fact, lay off your exposure instantly, well then, the first thing you do is start cancelling your surplus orders…

Between 2:32 p.m. and 2:45 p.m., as prices of the E-Mini rapidly declined, the Sell Algorithm sold about 35,000 E-Mini contracts (valued at approximately $1.9 billion) of the 75,000 intended. During the same time, all fundamental sellers combined sold more than 80,000 contracts net, while all fundamental buyers bought only about 50,000 contracts net, for a net fundamental imbalance of 30,000 contracts. This level of net selling by fundamental sellers is about 15 times larger compared to the same 13-minute interval during the previous three days, while this level of net buying by the fundamental buyers is about 10 times larger compared to the same time period during the previous three days.

In the report, they provide a definition:

We define fundamental sellers and fundamental buyers as market participants who are trading to accumulate or reduce a net long or short position. Reasons for fundamental buying and selling include gaining long-term exposure to a market as well as hedging already-existing exposures in related markets.

They would have been better off sticking to the street argot of “Real money” and “hot money”. Using the word “fundamental” implies the traders know what they’re doing, when I suspect most of the are simply cowboys and high-school students, marketting their keen insights into quantitative momentum-based computer-driven macro-strategies.

Many over-the-counter (“OTC”) market makers who would otherwise internally execute as principal a significant fraction of the buy and sell orders they receive from retail customers (i.e., “internalizers”) began routing most, if not all, of these orders directly to the public exchanges where they competed with other orders for immediately available, but dwindling, liquidity.

Even though after 2:45 p.m. prices in the E-Mini and SPY were recovering from their severe declines, sell orders placed for some individual securities and ETFs (including many retail stop-loss orders, triggered by declines in prices of those securities) found reduced buying interest, which led to further price declines in those securities.

OK, so a lot of stop-loss orders were routed through internalizers. Remember that; we’ll return to this point.

However, as liquidity completely evaporated in a number of individual securities and ETFs,11 participants instructed to sell (or buy) at the market found no immediately available buy interest (or sell interest) resulting in trades being executed at irrational prices as low as one penny or as high as $100,000. These trades occurred as a result of so-called stub quotes, which are quotes generated by market makers (or the exchanges on their behalf) at levels far away from the current market in order to fulfill continuous two-sided quoting obligations even when a market maker has withdrawn from active trading.

Stub quotes have to represent yet another triumph of the box-tickers. I mean, if you’re asking for continuous two-way markets as the price of privilege … shouldn’t you ensure that they’re meaningful two-way markets?

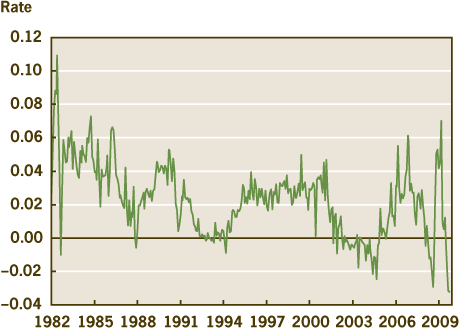

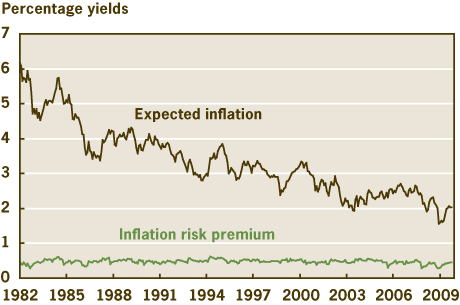

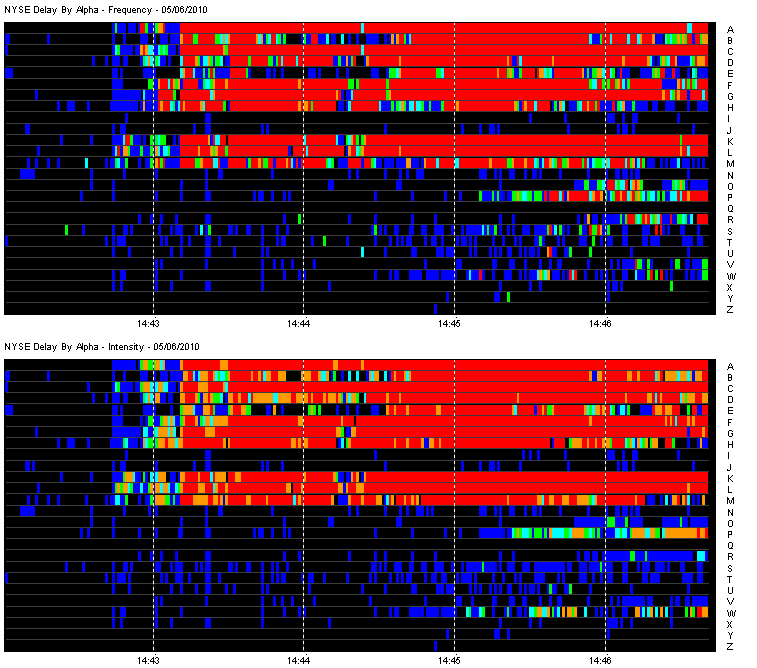

The summary briefly mentions the latency problem:

Although we do not believe significant market data delays were the primary factor in causing the events of May 6, our analyses of that day reveal the extent to which the actions of market participants can be influenced by uncertainty about, or delays in, market data.

The latency problem was discussed on August 9.

Now back to stop-losses:

For instance, some OTC internalizers reduced their internalization on sell-orders but continued to internalize buy-orders, as their position limit parameters were triggered. Other internalizers halted their internalization altogether. Among the rationales for lower rates of internalization were: very heavy sell pressure due to retail market and stop-loss orders, an unwillingness to further buy against those sells, data integrity questions due to rapid prices moves (and in some cases data latencies), and intra-day changes in P&L that triggered predefined limits.

…

As noted previously, many internalizers of retail order flow stopped executing as principal for their customers that afternoon, and instead sent orders to the exchanges, putting further pressure on the liquidity that remained in those venues. Many trades that originated from retail customers as stop-loss orders or market orders were converted to limit orders by internalizers prior to routing to the exchanges for execution. If that limit order could not be filled because the market continued to fall, then the internalizer set a new lower limit price and resubmitted the order, following the price down and eventually reaching unrealistically-low bids. Since internalizers were trading as riskless principal, many of these orders were marked as short even though the ultimate retail seller was not necessarily short.51 This partly helps explain the data in Table 7 of the Preliminary Report in which we had found that 70-90% of all trades executed at less than five cents were marked short.

That had really bothered me, so I’m glad that’s cleared up.

Detailed analysis of trade and order data revealed that one large internalizer (as a seller) and one large market maker (as a buyer) were party to over 50% of the share volume of broken trades, and for more than half of this volume they were counterparties to each other (i.e., 25% of the broken trade share volume was between this particular seller and buyer). Furthermore, in total, data show that internalizers were the sellers for almost half of all broken trade share volume. Given that internalizers generally process and route retail trading interest, this suggests that at least half of all broken trade share volume was due to retail customer sell orders.

…

In summary, our analysis of trades broken on May 6 reveals they were concentrated primarily among a few market participants. A significant number of those trades were driven by sell orders from retail customers sent to internalizers for immediate execution at then-current market prices. Internalizers, in turn, routed these orders to the public exchanges for execution at the NBBO. However, for those securities in which market makers had withdrawn their liquidity, there was insufficient buy interest, and many trades were executed at very low (and sometimes very high) prices, including stub quotes.

Stop-Loss: the world’s dumbest order-type.

In summary, this just shows that while the pool of hot money acting as a market-making buffer on price changes is very large, it can be exhausted … and when it’s exhausted, the same thing happens as when any buffer runs out.

Update: The Financial Post picked up a Reuters story:

The so-called flash crash sent the Dow Jones industrial average down some 700 points in minutes, exposing flaws in the electronic marketplace dominated by high-frequency trading.

I see no support for this statement at all. This was, very simply, just another case of market impact cost, distinguished only by its size. But blaming the HFT guys is fashionable this week…

Themis Trading has predicted:

- Alter the existing single stock circuit breaker to include a limit up/down feature….

- Eliminate stop-loss market orders….

- Eliminate stub quotes and allow one-sided quotes (a stub quote is basically a place holder that a market maker uses in order to provide a two-sided quote)…Exchanges also recently proposed a ban on stub quotes. They requested that all market makers be mandated to quote no more than 8% away from the NBBO for stocks in the circuit breaker pilot program and during the hours that the circuit breakers are in effect (9:45am-3:35pm ET). Exchanges proposed that market makers be mandated to quote no further than 20% away from the NBBO during the 15 minutes after the opening and 25 minutes before the close….

- Increase market maker requirements, including a minimal time for market makers to quote on the NBBO…..In addition, the larger HFTs believe that market makers should have higher capital requirements. Some smaller HFTs have not supported these proposed obligations, however. They fear that the larger HFTs will be able to meet these obligations and, in return, the larger HFTs will receive advantages from the exchanges that market makers usually enjoy. According to these smaller HFT’s, these advantages would include preferential access to the markets, lower fees and informational advantages. Smaller HFTs have warned that competition could be degraded and barriers to entry could be raised.

Ah, the good old compete-via-regulatory-capital-requirements game. Very popular, particularly in Canada.

And there’s at least one influential politician, Paul E. Kanjorski (D-PA), who wants to use the report to further his completely unrelated agenda:

“The SEC and CFTC report confirms that faster markets do not always lead to better markets,” said Chairman Kanjorski. “While automated, high-frequency trading may provide our markets with some benefits, it can also carry the potential for serious harm and market mischief. Extreme volatility of the kind we experienced on May 6 could happen again, as demonstrated by the volatility in individual stocks since then. To limit recurrences of that roller-coaster day and to bolster individual investor confidence, our regulators must expeditiously review and revise the rules governing market structure. Congress must also conduct oversight of these matters and, if necessary, put in place new rules of the road to ensure the fair, orderly and efficient functioning of the U.S. capital markets. The CFTC-SEC staff report will greatly assist in working toward these important policy goals.”

Update: FT Alphaville points out:

The CFTC, which wrote the report alongside the SEC, had previously downplayed that version of events but said it was looking into Nanex’s data. But Friday’s report explicitly contradicts Nanex’s take.

The Nanex explanation was last discussed on PrefBlog on August 17. The relevant section of the report, highlighted by FT Alphaville, is:

Some market participants and firms in the market data business have analyzed the CTS and CQS data delays of May 6, as well as the quoting patterns observed on a variety of other days. It has been hypothesized that these delays are due to a manipulative practice called “quote-stuffing” in which high volumes of quotes are purposely sent to exchanges in order to create data delays that would afford the firm sending these quotes a trading advantage.

Our investigation to date reveals that the largest and most erratic price moves observed on May 6 were caused by withdrawals of liquidity and the subsequent execution of trades at stub quotes. We have interviewed many of the participants who withdrew their liquidity, including those who were party to significant numbers of buys and sells that occurred at stub quote prices. As described throughout this report each market participant had many and varied reasons for its specific actions and decisions on May 6. For the subset of those liquidity providers who rely on CTS and CQS data for trading decisions or data- integrity checks, delays in those feeds would have influenced their actions. However, the evidence does not support the hypothesis that delays in the CTS and CQS feeds triggered or otherwise caused the extreme volatility in security prices observed that day.

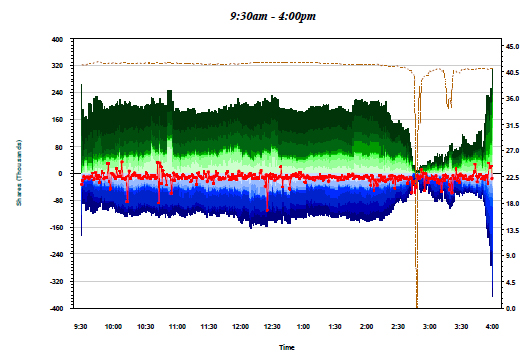

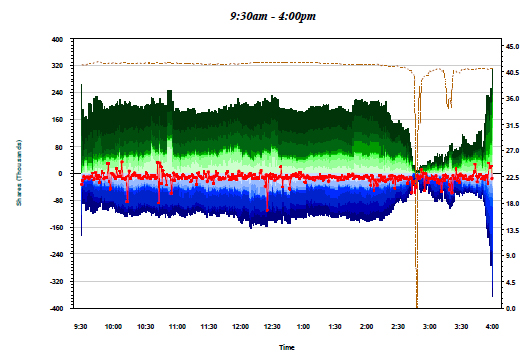

Update: The report has some very cool graphs of market depth – some of the Accenture ones are:

Accenture Order Book Depth – Day

Click for big

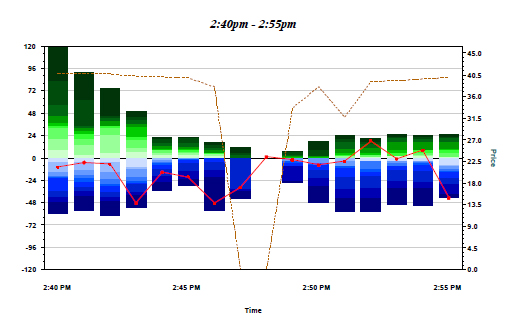

Accenture Order Book Depth – Close-up

Click for big

Legend

Click for big

Update, 2010-10-3: The report notes:

Some firms use multiple data sources as inputs to their data-integrity checks, and when those sources do not agree, a pause can be triggered. As discussed in Section 3, latency issues regarding a subset of pricing data on the consolidated market data feeds for NYSE-traded stocks triggered data-integrity checks in the systems of some firms. We refer to these as “feed-driven integrity pauses.”

Whenever data integrity was questioned for any reason, firms temporarily paused trading in either the offending security, or in a group of securities. As a firm paused its trading, any liquidity the firm may have been providing to the market became unavailable, and other firms that were still providing liquidity to the markets had to absorb continued order flow. To the extent that this led to more concentrated price pressure, additional rapid price moves would in turn trigger yet more price-driven integrity pauses.

…

Most market makers cited data integrity as a primary driver in their decision as to whether to provide liquidity at all, and if so, the manner (size and price) in which they would do so. On May 6, a number of market makers reported that rapid price moves in the E-Mini and individual securities triggered price-driven integrity pauses. Some, who also monitor the consolidated market data feeds, reported feed-driven integrity pauses. We note that even in instances where a market maker was not concerned (or even knowledgeable) about external issues related to feed latencies, or declarations of self-help, the very speed of price moves led some to question the accuracy of price information and, thus, to automatically withdraw liquidity. According to a number of market makers, their internal monitoring continuously triggered visual and audio alarms as multiple securities breached a variety of risk limits one after another.

…

For instance, market makers that track the prices of securities that are underlying components of an ETF are more likely to pause their trading if there are price-driven, or data feed-driven, integrity questions about those prices.37 Moreover, extreme volatility in component stocks makes it very difficult to accurately value an ETF in real-time. When this happens, market participants who would otherwise provide liquidity for such ETFs may widen their quotes or stop providing liquidity (in some cases by using stub quotes) until they can determine the reason for the rapid price movement or pricing irregularities.

This points to two potentially useful regulatory measures: imposing data-throughput minima on the exchanges providing data feeds; and the imposition of short trading halts (“circuit-breakers”) under certain conditions.

Update, 2015-4-22: The UK arrest of Navinder Singh Sarao has brought some interesting incompetence to light:

When Washington regulators did a five-month autopsy in 2010 of the plunge that briefly erased almost $1 trillion from U.S. stock prices, they didn’t consider individuals manipulating the market with fake orders because they used incomplete data.

Their analysis was upended Tuesday with the arrest of Navinder Singh Sarao — a U.K.-based trader accused by U.S. authorities of abusive algorithmic trading dating back to 2009. The episode shows fundamental cracks in the way some of the world’s most important markets are regulated, from the exchanges that get to police themselves to the government departments that complain they don’t have adequate resources to do their jobs.

…

It turns out regulators may have missed Sarao’s activity because they weren’t looking at the right data, according to former CFTC Chief Economist Andrei Kirilenko, who co-authored the report. He said in an interview that the CFTC and SEC based their study of the sorts of futures Sarao traded primarily on completed transactions, which wouldn’t include the thousands of allegedly deceitful orders that Sarao submitted and immediately canceled.

On the day of the flash crash, Sarao used “layering” and “spoofing” algorithms to enter orders for thousands of futures on the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. The orders amounted to about $200 million worth of bets that the market would fall, a trade that represented between 20 percent and 29 percent of all sell orders at the time. The orders were then replaced or modified 19,000 times before being canceled in the afternoon. None were filled, according to the affidavit.

…

SEC Commissioner Michael Piwowar, speaking Wednesday at an event in Montreal, said there needs to be a full investigation into whether the SEC or CFTC botched the flash crash analysis.

“I fully expect Congress to be involved in this,” he said.

Senator Richard Shelby, the Alabama Republican who heads the banking committee, said in a statement Wednesday that he intends to look into questions raised by Sarao’s arrest.

Mark Wetjen, a CFTC commissioner speaking at the same event, echoed Piwowar’s concerns about regulators’ understanding of the events.

“Everyone needs to have a deeper, better understanding of interconnections of derivatives markets on one hand and whatever related market is at issue,” Wetjen said. “It doesn’t seem like that was really addressed or looked at in that report.”