The Anginer and Yıldızhan paper recently discussed on PrefBlog that attempted to corellate credit spreads with equity returns referenced a paper by Jing-zhi Huang and Ming Huang titled How Much of Corporate-Treasury Yield Spread is Due to Credit Risk?: A New Calibration, presented at the 14th Annual Conference on Financial Economics and Accounting:

No consensus has yet emerged from the existing credit risk literature on how much of the observed corporate-Treasury yield spreads can be explained by credit risk. In this paper, we propose a new calibration approach based on historical default data and show that one can indeed obtain consistent estimate of the credit spread across many different economic considerations within the structural framework of credit risk valuation. We find that credit risk accounts for only a small fraction of the observed corporate-Treasury yield spreads for investment grade bonds of all maturities, with the fraction smaller for bonds of shorter maturities; and that it accounts for a much higher fraction of yield spreads for junk bonds. We obtain these results by calibrating each of the models – both existing and new ones – to be consistent with data on historical default loss experience. Different structural models, which in theory can still generate a very large range of credit spreads, are shown to predict fairly similar credit spreads under empirically reasonable parameter choices, resulting in the robustness of our conclusion.

They note:

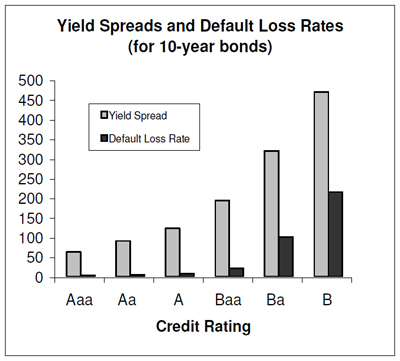

One common finding from these studies is that the average historical default loss rate for corporate bonds is typically much smaller than the observed corporate-Treasury yield spreads, and is only a small fraction of the yield spreads for investment-grade bonds. Figure 1 provides a visual summary of this finding.

They point out:

This fact alone, however, should not lead one to automatically conclude that credit risk accounts for only a small fraction of the observed yield spreads for investment grade bonds. After all, the expected default loss rate is only part of the (promised) credit yield spread; the other part is the credit risk premium, defined as the difference between the expected realized return of a defaultable bond and that of a comparable Treasury bond. The credit risk premium is required by investors because the uncertainty of default loss should be systematic—bondholders are more likely to suffer default losses in bad states of the economy. Moreover, precisely because of the tendency for default events to cluster in the worst states of the economy, the credit risk premium can be potentially very large. In fact, some of the models considered in this paper can indeed generate credit risk premia that are large enough to explain the difference between the observed corporate yield spreads and historical default loss rate, provided that certain parameter choices are made. The key question, however, is whether any model can generate such large credit risk premia under empirically reasonable parameter choices. This question is the main focus of our paper.

They conclude:

We conclude that, for investment grade bonds (those with a credit rating not lower than Baa) of all maturities, credit risk accounts for only a small fraction—typically around 20%, and, for Baa-rated bonds, in the 30% range—of the observed corporate-Treasury yield spreads, and it accounts for a smaller fraction of the observed spreads for bonds of shorter maturities. For junk bonds, however, credit risk accounts for a much larger fraction of the observed corporate-Treasury yield spreads.

This study looks at 10-year corporates. I once used 20 years of S&P historical 5 year default and recovery data to estimate the lowest a corporate spread ever got was twice the expected losses. My data showed a nice exponential relationship between expected losses and credit rating — similar to this figure, but clearly linear when log of expected losses was used for the Y-Axis.

Obviously, in a recession the probability of losses increases beyond the long run average, so spreads widen. In the good times, spreads almost never get below 2X long run expected losses because a recession could occur prior to maturity.

I am not sure I buy the argument that the additional spread beyond expected losses rises in a recession due to systemic factors. I see the expected loss spread as comparable to stock beta (which is the systemic part already). With stocks we can diversify idiosyncratic risk, but are left with beta risk. With corporate bonds we can likewise diversify idiosycratic risk, but are left with expected losses — a risk that requires compensation.

It is entirely reasonable that the additional factor beyond expected losses (labeled credit risk premium in the cited article) be about the same size as the expected losses — after all, the past may not predict the future and the risk of larger losses is proportional to the expected losses.

That is exactly why I don’t think the US government (nor anybody else, for that matter) should be buying bad bank debt at a price reflecting “expected losses”. If the expectations are correct and unbiased, the expected return is only the risk-free Treasury rate — zero compensation for the added risk taken. In a rational market, a fair price is a spread of at least 2X expected losses.