Mark J. Flannery Bank of America Eminent Scholar Chair of Finance at the University of Florida proposed Reverse Convertible Debentures in 2002 in his paper No Pain, No Gain? Effecting Market Discipline via “Reverse Convertible Debentures”:

The deadweight costs of financial distress limit many firms’ incentive to include a lot of (taxadvantaged) debt in their capital structures. It is therefore puzzling that firms do not make advance arrangements to re-capitalize themselves if large losses occur. Financial distress may be particularly important for large banking firms, which national supervisors are reluctant to let fail. The supervisors’ inclination to support large financial firms when they become troubled mitigates the ex ante incentives of market investors to discipline these firms. This paper proposes a new financial instrument that forestalls financial distress without distorting bank shareholders’ risk-taking incentives. “Reverse convertible debentures” (RCD) would automatically convert to common equity if a bank’s market capital ratio falls below some stated value. RCD provide a transparent mechanism for un-levering a firm if the need arises. Unlike conventional convertible bonds, RCD convert at the stock’s current market price, which forces shareholders to bear the full cost of their risk-taking decisions. Surprisingly, RCD investors are exposed to very limited credit risk under plausible conditions.

Of interest is the example of some Manny-Hanny bonds:

The case of Manufacturers Hanover (MH) in 1990 illustrates the problem. The bank had issued $85 million dollars worth of “mandatory preferred stock,” which was scheduled to convert to common shares in 1993. An earlier conversion would be triggered if MH’s share price closed below $16 for 12 out of 15 consecutive trading days (Hilder [1990]). Such forced conversion appeared possible in December 1990. In a letter to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concerning the bank’s capital situation, MH’s CFO (Peter J. Tobin) expresses the bank’s extreme reluctance to permit conversion, or to issue new equity at current prices. At yearend 1990, MH’s book ratio of equity capital to total (on-book) assets was 5.57%, while its market equity ratio was 2.53%. The bank was also adamant in announcing that it would not omit its quarterly dividend. Despite the low market capital ratio, the Fed appeared unable to force MH to issue new equity. Chemical Bank acquired Manufacturers Hanover at the end of 1991.

…

When Manufacturers’ Hanover confronted a possible conversion of preferred stock in late 1990 (see footnote 6), they considered redeeming the issue using cash on hand. Such a “plan” only works if a supervisor will accept it. Under a market value trigger, such redemption would have to be financed by issuing equity; otherwise, the redemption would further lower the capital ratio. Another important feature of the MH convertible preferred issue was that the entire issue converted if common share prices were even $.01 too low over the specified time interval.

Flannery proposes the following design parameters for RCD:

RCD would have the following broad design features:

- 1. They automatically convert into common equity if the issuer’s capital ratio falls below a pre-specified value.

- 2. Unless converted into shares, RCD receive tax-deductible interest payments and are subordinated to all other debt obligations.

- 3. The critical capital ratio is measured in terms of outstanding equity’s market value. (See Section III.)

- 4. The conversion price is the current share price. Unlike traditional convertible bonds, one dollar of debentures (in current market value) would generally convert into one dollar’s worth of common stock.

- 5. RCD incorporate no options for either investors or shareholders: conversion occurs automatically when the trigger is tripped.

- 6. When debentures convert, the firm must promptly sell new RCD to replace the converted ones.

An example of RCD conversion is provided:

The bank in Figure 1 starts out at t = 0 with a minimally acceptable 8% capital ratio, backed by RCD equal to an additional 5% of total assets. With ten shares (“N”) outstanding, the initial share price (“PS”) is $0.80. By t = ½, the bank’s asset value has fallen to $97, leaving equity at $5.00 and the share price at $0.50. The bank is now under-capitalized ($5/$97 = 5.15% < 8%). Required capital is $7.76 (= 8% of $97). The balance sheet for t = 1 shows that $2.76 of RCD converted into equity to restore capital to 8% of assets. Given that PS = $0.50 at t = ½, RCD investors receive 5.52 shares in return for their $2.76 of bond claims. These investors lose no principal value when their debentures convert: they can sell their converted shares at $0.50 each and use the proceeds to re-purchase $2.76 worth of bonds. The initial shareholders lose the option to continue operating with low equity, because they must share the firm’s future cash flows with converted bondholders.

The critical part of this structure is that the triggering capital ratio values outstanding equity at market prices, rather than book. Additionally, not all – not necessarily even all of one issue – gets converted. Flannery suggests that issues be converted in the order of their issuance; first-in-first-out.

A substantial part of the paper consists of a defense of this market value feature, which I shall not reproduce here.

Flannery repeatedly touts a feature of the plan that I consider a bug:

Triggered by a frequently-evaluated ratio of equity’s market value to assets, RCD could be nearly riskless to the initial investors, while transmitting the full effect of poor investment outcomes to the shareholders who control the firm.

I don’t like the feature. I believe that a fixed-price conversion with a fixed-price trigger will aid in the analysis of this type of issue and make it easier for banks to sell equity above the trigger point – which is desirable! It is much better if the troubled bank can sell new equity to the public at a given price than to have the RCDs convert – Flannery worries about a requirement that the banks replace converted RCDs in short order, which is avoided if the trigger is avoided. If new equity prospects are not aware of their possible dilution if bad times become even worse, they will be less eager to buy.

Additionally, I am not enamoured of the use of regulatory asset weightings as a component of the trigger point. The last two years have made it very clear that there is a very wide range of values that may be assigned to illiquid assets; honest people can legitimately disagree, sometimes by amounts that are very material.

Market trust in the quality of the banks’ mark-to-market of its assets will be reflected, at least to some degree, by the Price/Book ratio. So let’s re-work Flannery’s Table 1 for two banks; both with the same initial capitalization; both of which mark down their assets by the same amount; but one of which maintains its Price/Book ratio (investors trust bank management) while the other’s P/B ratio declines (investors don’t trust bank management, or for some other reason believe that the end of the write-downs is yet to come).

Note that Flannery’s specification for the Market Ratio:

The market value equity ratio is the market value of common stock divided by the sum of (the book value of total liabilities plus the market value of common stock).

| Two banks: t=0 | |

| Trusty Bank | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| 100 | 87 Deposits 5 RCD 8 Equity |

| N = 10, Book = $0.80, Price = $1.20; Market Ratio = 12/(87+5+12) = 11.5% |

Sleazy Bank |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| 100 | 87 Deposits 5 RCD 8 Equity |

| N = 10, Book = $0.80, Price = $1.20; Market Ratio = 12/(87+5+12) = 11.5% |

|

This is basically the same as Flannery’s example; however, he uses a constant P/B ratio of 1.0 to derive a Market Ratio of 8%. In addition, I will assume that the regulatory requirement for the Market Ratio is 10% – the two banks started with a cushion.

Disaster strikes at time t=0.5, when asset values decline by 3%. Trusty Bank’s P/B remains constant at 1.5, but Sleazy Bank’s P/B declines to 0.8.

| Two banks: t=0.5 | |

| Trusty Bank | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| 97 | 87 Deposits 5 RCD 5 Equity |

| N = 10, Book = $0.50, Price = $0.75; Market Ratio = 7.50 / (87+5+7.5) = 7.54% |

Sleazy Bank |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| 97 | 87 Deposits 5 RCD 5 Equity |

| N = 10, Book = $0.50, Price = $0.40; Market Ratio = 4.00 / (87+5+4) = 4.17% |

|

In order to get its Market Ratio back up to the 10% regulatory minimum that is assumed, Trusty Bank needs to solve the equation:

[7.5+x] / [87 + (5-x) + (7.5 + x)] = 0.10

where x is the Market Value of the new equity and is found to be equal to 2.45. With a stock price of 0.75, this is equal to 3.27 shares

Sleazy Bank solves the equation:

[4.0+x] / (87 + (5-x) + (4.0 +x)) = 0.10

and finds that x is 5.60. With a stock price of 0.40, this is equal to 14.00 shares.

| Two banks: t=1.0 | |

| Trusty Bank | |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| 97 | 87 Deposits 2.55 RCD 7.45 Equity |

| N = 13.27, Book = $0.56, Price = $0.75; Market Ratio = (13.27*0.75)/(87+2.55+(13.27*0.75)) = 10% |

Sleazy Bank |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| 97 | 87 Deposits -0.60 RCD 10.60 Equity |

| N = 24.00, Book = $0.44, Price = $0.40; Market Ratio = (24*0.4)/(87-0.6+(24*0.4)) = 10% |

|

Sleazy Bank doesn’t have the capital on hand – as shown by the negative value of balance sheet RCD at t=1 – so it goes bust instead. In effect, there has been a bank run instigated not by depositors but by shareholders.

Note that in the calculations I have assumed that the price of the common does not change as a result of the dilution; this alters the P/B ratio. Trusty Bank’s P/B moves from 1.50 to 1.34; Sleazy Bank’s P/B (ignoring the effect of the negative value of the RCDs) moves from 0.8 to 0.91. Whether or not the assumption of constant market price is valid in the face of the dilution is a topic that can be discussed at great length.

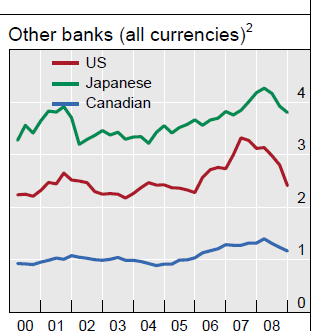

I will note that the Price/Book ratio of Japanese banks in early 2008 was 0.32:1 and Citigroup’s P/B ratio is currently 0.67:1.

While Dr. Flannery’s idea has its attractions, I am very hesitant about the idea of mixing book and market values. From a theoretical viewpoint, capital is intended to be permanent, which implies that once the bank has its hands on the money, it doesn’t really care all that much about the price its capital trades at in the market.

Using a fixed conversion price, with a fixed market price trigger keeps the separation of book accounting from market pricing in place, which offers greater predictability to banks, investors and potential investors in times of trouble.

Update 2009-11-1: Arithmetical error corrected in table.

It should also be noted that the use of market value of equity in calculating regulatory ratios makes the proposal as it stands extremely procyclical.