I referred to the paper on September 15 and republished the abstract in that post.

The paper is by Amir E. Khandani, a graduate student at MIT, and Andrew W. Low, a Professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management (among other titles).

The paper was written in an attempt to understand the events of August 7th to August 10th:

With laser-like precision, model-driven long/short equity funds were hit hard on Tuesday August 7th and Wednesday August 8th, despite relatively little movement in fixed-income and equity markets during those two days and no major losses reported in any other hedge-fund sectors. Then, on Thursday August 9th when the S&P 500 lost nearly 3%, most of these market-neutral funds continued their losses, calling into question their market-neutral status.

By Friday, August 10th, the combination of movements in equity prices that caused the losses earlier in the week had reversed themselves, rebounding significantly but not completely. However, faced with mounting losses on the 7th, 8th, and 9th that exceeded all the standard statistical thresholds for extreme returns, many of the affected funds had cut their risk exposures along the way, which only served to exacerbate their losses while causing them to miss out on a portion of the reversals on the 10th. And just as quickly as it descended upon the quants, the perfect financial storm was over.

I’ll quibble with the idea that taking losses when the market goes down calls into question their market-neutral status. Ideally, the distribution of gains and losses for such a fund will be completely uncorrelated with market movements; there will be just as many opposites as there are matches over a sufficiently long time period (like, more than a week!).

The authors define the class of hedge fund investigated as:

including any equity portfolios that engage in shortselling, that may or may not be market-neutral (many long/short equity funds are long-biased), that may or may not be quantitative (fundamental stock-pickers sometimes engage in short positions to hedge their market exposure as well as to bet on poor-performing stocks), and where technology need not play an important role.

… but warn that distinctions between funds are blurring (similarly to recently observed private-equity investments in junk bonds).

The authors attempt to reproduce the overall performance of the model-driven long/short equity funds by use of a naive model:

consider a long/short market-neutral equity strategy consisting of an equal dollar amount of long and short positions, where at each rebalancing interval, the long positions are made up of “losers” (underperforming stocks, relative to some market average) and the short positions are made up of “winners” (outperforming stocks, relative to the same market average).

…

By buying yesterday’s losers and selling yesterday’s winners at each date, such a strategy actively bets on mean reversion across all N stocks, profiting from reversals that occur within the rebalancing interval. For this reason, (1) has been called a “contrarian” trading strategy that benefits from market overreaction, i.e., when underperformance is followed by positive returns and vice-versa for outperformance

And at this point in the paper I got extremely excited, because the following paragraph proves these guys have actually thought about what they’re saying (which is extremely unusual):

However, another source of profitability of contrarian trading strategies is the fact that they provide liquidity to the marketplace. By definition, losers are stocks that have under-performed relative to some market average, implying a supply/demand imbalance, i.e., an excess supply that caused the prices of those securities to drop, and vice-versa for winners. By buying losers and selling winners, contrarians are increasing the demand for losers and increasing the supply of winners, thereby stabilizing supply/demand imbalances. Traditionally, designated marketmakers such as the NYSE/AMEX specialists and NASDAQ dealers have played this role, for which they are compensated through the bid/offer spread. But over the last decade, hedge funds and proprietary trading desks have begun to compete with traditional marketmakers, adding enormous amounts of liquidity to U.S. stock markets and earning attractive returns for themselves and their investors in the process.

The concept of “selling liquidity” is central to the Hymas Investment Management investment philosophy.

The naive strategy works extemely well:

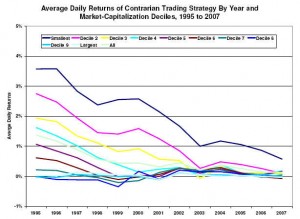

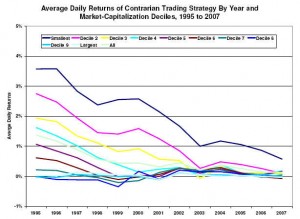

In 1995, the average daily return of the contrarian strategy for all stocks in our sample is 1.38%, but by 2000, the average daily return drops to 0.44% and the year-to-date figure for 2007 (up to August 31) is 0:13%. Figure 1 illustrates the near-monotonic decline of the expected returns of this strategy, no doubt a reflection of increased competition, changes in market structure, improvements in trading technology and electronic connectivity, the growth in assets devoted to this type of strategy, and the corresponding decline in U.S. equity-market volatility over the last decade. This secular decline in profitability has significant implications for the use of leverage, which we will explore in Section 6.

These trends are consistent with my own informal observations. The authors suggest that the problem of declining returns may have been addressed by the simple expedient of increasing leverage … where have I heard that one before? But the naive method data is interesting – maybe I’ll do something like this for preferreds some day!

So what happened during the period at issue?

The three days in the second week, August 7th, 8th, and 9th are the outliers, with losses of -1.16%, -2.83%, and -2.86%, respectively, yielding a cumulative three-day loss of -6.85%. Although this three-day return may not seem that significant – especially in the hedge-fund world where volatility is a fact of life – note from Table 2 that the contrarian strategy’s 2006 daily standard deviation is 0.52%, so a -6.85% cumulative return represents a loss of 12 daily standard deviations! Moreover, many long/short equity managers were employing leverage (see Section 6 for further discussion), hence their realized returns were magnified several-fold.

Curiously, a significant fraction of the losses was reversed on Friday, August 10th, when the contrarian strategy yielded a return of 5.92%, which was another extreme outlier of 11.4 daily standard deviations. In fact, the strategy’s cumulative return for the entire week of August 6th was -0.43%, not an unusual weekly return in any respect.

We could quibble over the use of “standard deviations” in the above, but we won’t. We’ve already done that.

The authors provide a variety of rationales for excess losses experienced by real hedge funds, cautioning that they have no access to the books and are therefore only guessing. What makes sense to me is the following scenario:

- Randomly selected hedge fund does a large liquidation (either by change in strategy, or to meet client redemption

- Market impact for this liquidation distorts the market for several days

- By policy or by counterparty insistence, funds unwind positions after losses, and

- hence, do not share in the excess returns seen Friday

It all hangs together. The scariest and funniest part of the paper is:

Moreover, the widespread use of standardized factor risk models such as those from MSCI/BARRA or Northfield Information Systems by many quantitative managers will almost certainly create common exposures among those managers to the risk factors contained in such platforms.

But even more significant is the fact that many of these empirical regularities have been incorporated into non-quantitative equity investment processes, including fundamental “bottom-up” valuation approaches like value/growth characteristics, earnings quality, and financial ratio analysis. Therefore, a sudden liquidation of a quantitative equity market-neutral portfolio could have far broader repercussions, depending on that portfolio’s specific factor exposures.

So the scary part is: this is cliff-risk come to equities, cliff-risk having been discussed – briefly – on PrefBlog on April 4. The funny part is: we have an enormous industry with enormously compensated personnel that wind up all making the same bet (or, at least, bets all having extremely similar common factors). It’s all sales!

Update, 2010-8-6: There are claims that the 2010-5-6 Flash Crash had similar origins:

Critics focus on unusual market volatility experienced in August 2007 and again during the “flash crash” of May 2010 to show why HFT has increased rather than reduced volatility. The essential similarity among many quant strategies results in trades becoming crowded, and the application of HFT techniques ensures that when they go wrong it results in a disorderly rush for the exits.

The August 2007 and May 2010 episodes were the only ones involving high-frequency computer-driven trading. But the same basic problem (automated quant-based strategies and crowded trades causing liquidity to disappear in a crisis) can be traced back to previous market crises in 1998 (the failure of Long-Term Capital Management) and October 1987 (portfolio insurance and the stock market plunge), according to critics.