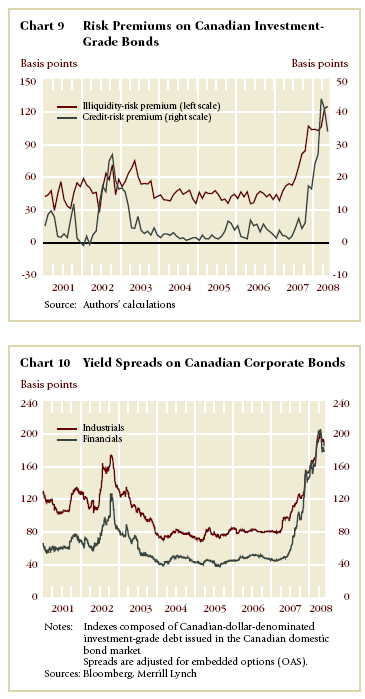

It has long been a criticism of the structural Merton models of default that they calculate credit spreads that are much lower than those observed in the market. The Bank of England and the Bank of Canada take what I feel is a sensible course and ascribe the excess spread to liquidity concerns.

Liquidity, however, is a kind of touchy-feely concept and there is a yearning to quantify credit spreads such that, ideally, every single beep could be assigned to some kind of rational formula, base largely on default probability. In the Bank of Canada paper referenced above, the authors note:

Recent research that expands structural models by including them in a broader macroeconomic setting has shown that credit-risk premiums may, in fact, account for a larger portion of the overall spread than indicated by the “traditional” structural model (Chen 2008). This suggests that the results of “traditional” structural models such as that used in this study should be interpreted with caution, and should focus on the direction in which risk factors evolve, rather than on the specific values of the relative contributions of the factors.

The Chen paper is available on-line: Macroeconomic Conditions and the Puzzles of Credit Spreads and Capital Structure:

This paper addresses two puzzles about corporate debt: the “credit spread puzzle” – why yield spreads between corporate bonds and treasuries are high and volatile – and the “under-leverage puzzle” – why firms use debt conservatively despite seemingly large tax benefits and low costs of financial distress. I propose a unified explanation for both puzzles: investors demand high risk premia for holding defaultable claims, including corporate bonds and levered firms, because (i) defaults tend to concentrate in bad times when marginal utility is high; (ii) default losses are also higher during such times. I study these comovements in a structural model, which endogenizes firms’ financing and default decisions in an economy with business-cycle variation in expected growth rates and economic uncertainty. These dynamics coupled with recursive preferences generate countercyclical variation in risk prices, default probabilities, and default losses. The credit risk premia in my calibrated model are large enough to account for most of the high spreads and low leverage ratios. Relative to a standard structural model without business-cycle variation, the average spread between Baa and Aaa-rated bonds rises from 48 bp to around 100 bp, while the average optimal leverage ratio of a Baa-rated firm drops from 67% to 42%, both close to the U.S. data.

He points out:

One can not resolve the puzzles simply by raising the risk aversion. While a higher risk aversion does push up the credit spreads, it increases the equity premium dramatically. Moreover, a higher risk aversion actually increases the leverage ratio. It does increase the expected costs of financial distress, which leads to lower optimal coupon rate lower and higher interest coverage. However, a drop in debt value comes with a bigger drop in equity value, resulting in a higher leverage ratio.

The guts of the argument is:

First, marginal utilities are high in recessions, which means that the default losses that occur during such times will affect investors more. Second, recessions are also times when cash flows are expected to grow slower and become more volatile. These factors, combined with higher risk prices at such times, imply lower continuation values for equity-holders, which make firms more likely to default in recessions. Third, since many firms are experiencing problems in recessions, asset liquidation can be particularly costly, which will result in higher default losses for bond and equity-holders. Taken together, the countercyclical variation in risk prices, default probabilities, and default losses raises the present value of expected default losses for bond and equity-holders, which leads to high credit spreads and low leverage ratios.

Frankly, I don’t consider the paper very satisfying. While the argument appears sound, the actual model is too highly parameterized to allow for high confidence in the outputs; in other words, I fear that a variation of data mining has come into play. Additionally, I am highly suspicious of arguments that assume the market is rational and that an objective evaluation of default risk is (essentially) the only factor determining credit spreads. That’s not what I see in the market.

What I see is a lot of segmentation (some investors will not buy corporates. Some investors will buy corporates, but will dump and run at the first whiff of difficulties) and a high liquidity premium – these are two factors not considered in the model.