In the comments to my post Is the US Banking System Really Insolvent? Prof. Menzie Chin brought to my attention a wonderful paper: Leveraged Losses: Lessons from the Mortgage Market Meltdown.

This paper has also been highlighted on Econbrowser under the title Tabulating the Credit Crunch’s Effects: One Educated Guess.

The source document is in several parts – to do justice to it, I will be be posting reviews of each section. In this post, I will examine Part 3: Estimating Mortgage Credit Losses.

The first method of estimation is described thus:

The mechanics of these estimates is best explained by focusing on the $243 billion baseline estimate produced by the global bank analysts at Goldman Sachs. Their model simply extrapolates the performance – defaults, loss severities, and total loss rates – of each “vintage” (origination year) of subprime and other mortgage loans, based on its own history as well as the typical progression pattern through time. For example, suppose that the cumulative default rate on the 2006 subprime vintage is 3% at the end of 2007. Suppose further that the 2004 vintage showed a cumulative default rate of 1% after 1 year and 4% after 3 years, i.e. a fourfold increase over 2 additional years. Their procedure is to use the data on the 2004 vintage to extrapolate the cumulative default rate on the 2006 vintage. In this scenario, the default rate on the 2006 vintage would be 12% by the year 2009.

This methodology is, of course, complete nonsense. While I am sure that it is possible to determine a factor that correlates time from origination with cumulative loss experience, it is totally unacceptable to consider this the sole factor. As the authors state in the introduction to section 3.2 regarding adjustments to this baseline forecast:

Although the modeling strategy described above seems quite logical, it does not account for the possibility of a structural break that might result from falling home prices. In particular, because the detailed mortgage performance data required to build these types of models are available only back to the mid-1990s, there are no observations on how defaults and losses on a particular vintage change through time when home prices start to fall.

It would seem much more logical to consider – at least! – a three-factor model, which would incorporate the effect of negative equity on default rates and some measure of income … in other words, the good old “asset coverage” and “income coverage” tests that will be so familar to PrefBlog’s readers. The authors do not do this, nor do they attempt to do this – they simply increase the subprime default rates by one third and assume that non-subprime [you can’t call this “prime”, because of the “jumbo” and “Alt-A” netherworlds] defaults rise to one-half of the historical peak to arrive at an estimate of $400-billion total losses.

While the authors admit that these assumptions are extremely arbitrary, I will go a bit further and say that they are so arbitrary that their inclusion detracts from the credibility of the paper.

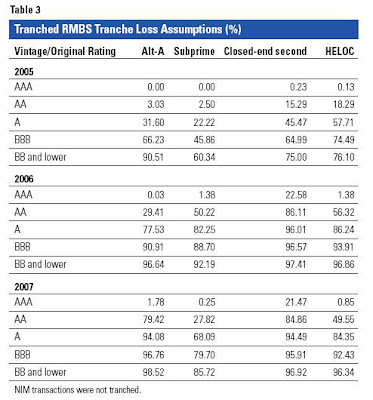

The second method sets up a grid analyzing total sub-prime issuance of $1,402-billion into cells determined by tranche rating and vintage. Each cell is then multiplied by the price of the ABX contract corresponding to that cell to calculate a loss estimate. The authors present their data as Exhibits 3.2, 3.3 and 3.4; a highly abbreviated summary of the data is:

| Abbreviated Version of Loss Estimate | |||

| Tranche | Nominal Value |

Loss Factor (Weighted Average) |

Loss |

| AAA | 1,133 | 18.9% | 214 |

| AA | 135 | 43.0% | 58 |

| A | 70 | 65.7% | 46 |

| BBB | 49 | 79.6% | 39 |

| BB/Other | 15 | 86.7% | 13 |

| Total | 1,402 | 371 | |

The authors note:

There are many caveats that come with these estimates. We know that trading is thin in the underlying loan pools. More importantly, the ABX prices probably include a risk premium that is necessary to induce investors to bear mortgage credit risk in the current mortgage credit crisis. It may therefore overstate the market’s true expectation of future losses, although the size of this overstatement is difficult to gauge. Nonetheless, it is interesting to us that the range of losses from this exercise is not too different from the one obtained using method one calculations.

I will go so far as to say that the risk premium “probably” included in ABX prices is probably dominant. Let’s have a look at some analysis that at least purports to be an analysis, rather than an academic exercise in applying the Efficient Market Hypothesis. From Accrued Interest‘s post S&P on the monolines: No problem. Why?:

I will note that the Fitch stress test of RMBS, noted in their recent report on insurance companies, allows for a 5% loss on AAA, 30% on AA and 100% on everything else.

It is quite apparent that – regardless of the loss of information inherent in my presentation of highly compressed versions of the authors’ calculations – that there are huge differences between “price” and “value”, where price is defined by reference to the ABX indices and value is defined by S&P’s cumulative default projections.

I will not make an impassioned defense of S&P here, nor will I repeat the concerns about the ABX indices that I raised in response to Prof. James Hamiltion’s Econbrowser post “Mortgage Securitization“. I will, however, point out that it seems rather intellectually dishonest not to include any “bottom up” analyses that might, possibly, give rise to smaller numbers in this review article. If the authors don’t place any credence in the estimates – that’s fine, let them say so. But completely ignoring such estimates detracts further from the paper’s credibility.

The paper’s third method of estimation is much more robust. The authors examine prior experience in three states (California (1991-1997), Texas (1986-1989) and Massachussets (1990-1993)) that experienced sharp declines in housing prices and arrive at potential foreclosure rates in the current crisis by comparison:

Hence, we conclude from our analysis that a housing downturn that resembled the three regional busts, with a 10%-15% peak-to-trough home price fall, could triple the national foreclosure rate over the next few years. This would imply a rise from 0.4% in mid-2006 to 1.2% in 2008 or 2009. Once home prices recover, the foreclosure rate might gradually fall back toward 0.4%.

Unfortunately, the authors spoil a good start by making an aggressive assumption in the course of their calculation:

These assumptions imply cumulative “excess” foreclosures of 13.5% of the currently outstanding stock of mortgages over the next few years. [Note: The calculation is that the foreclosure rate exceeds its baseline level by an average of 0.48 percentage points per quarter for a 7-year period, which implies cumulative excess foreclosures of 13.5%.]

A seven year period? A severe nation-wide recession lasting seven years sounds more like a depression to me. Additionally, the authors arrive at this figure by tripling the mid-2006 foreclosure figure of 0.4%, when the tripling in the states’ data was achieved from base rates of about 0.2%.

To be fair, though, I will note the recent Mortgage Bankers’ Associate press release:

The delinquency rate does not include loans in the process of foreclosure. The percentage of loans in the foreclosure process was 2.04 percent of all loans outstanding at the end of the fourth quarter, an increase of 35 basis points from the third quarter of 2007 and 85 basis points from one year ago.

The rate of loans entering the foreclosure process was 0.83 percent on a seasonally adjusted basis, five basis points higher than the previous quarter and up 29 basis points from one year ago.

The total delinquency rate is the highest in the MBA survey since 1985. The rate of foreclosure starts and the percent of loans in the process of foreclosure are at the highest levels ever.

The increase in foreclosure starts was due to increases for both prime and subprime loans. From the previous quarter, prime fixed rate loan foreclosure starts remained unchanged at 0.22 percent, but prime ARM foreclosure starts increased four basis points to 1.06 percent. Subprime fixed foreclosure starts increased 14 basis points to 1.52 percent and subprime ARM foreclosure starts increased 57 basis points to 5.29 percent. FHA foreclosure starts decreased 4 basis points to 0.91 percent and VA foreclosure starts remained unchanged at 0.39.

Their figure of 13.5% cumulative foreclosures is then applied to $11-trillion of total mortgage debt to arrive at foreclosure starts of $1.5-trillion. These foreclosure starts turn into actual repossessions at a rate of 55-60%, and the authors claim average loss severity of 50%, to arrive at total losses (over seven years, remember) of $400-billion.

Quite frankly, their phrasing of the justification of the 55-60% repossession strikes me as a little suspicious:

However, the percentage of all foreclosure starts that turn into repossessions – measured by the number of Real Estate Owned (REO) notices divided by the lagged number of Notices of Default (NoD) – has recently risen to over 50% according to Data Quick, Inc., a real estate information company.

It’s only recently risen to over 50%? What is it normally? What was it in the data that has been presented for the three states that give rise to the “tripling” statistic? There has been a lot of analysis to the effect that a lot of sub-prime mortgages didn’t even make their first payment – which is taken as a warning flag of intentional fraud. Has this been accounted for?

Quite frankly, there are too many unanswered questions here for me to take the loss estimates seriously. I will stress: I am not taking a position on what the actual level of subprime losses will be. I am, however, pleading desperately for a credible estimate.

I will note that Larry Summers thinks $400-billion total is optomistic.

Update, 2008-3-8: There is a laudatory article in the Economist:

The study begins by estimating the size of mortgage-related losses using three different methods.

…

Each method involves some heroic assumptions.

…

Strikingly, however, all three approaches yield similar results: that mortgage-credit losses are likely to be around $400 billion.

Not only are the assumptions heroic, they are not supported by evidence or argument. There is no indication in the paper that they are anything other than “plugs” … a factor used to ensure you get the result you want. It is therefore not terribly impressive that all three approaches yield similar results … whatever happened to critical thinking?

Update, 2008-3-23: Here are PIMCO’s views on the matter, as of January 2008:

In order to measure the distance to a resolution of the problem, we need to estimate the extent of the valuation losses in subprime loans and related products. There is no clear answer, but data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggest subprime losses of $300 billion. Roughly speaking, this is equivalent to 15% (40% default rate times 40% loss rate) of the $2 trillion in outstanding subprime home mortgages including Alt-A loans. However, judging from losses announced recently by financial institutions, we believe that actual overall subprime losses come to nearly double this figure or approximately $500 billion. This is because in addition to losses on subprime loans themselves, there were also steep valuation losses on other securitized products that make up nearly half the total. Financial institutions have an exposure of about 40%, so we believe that their latent losses amount to $200-250 billion.

Let us now examine the disparity between these potential losses and the actual losses (including valuation losses) posted by financial institutions. Losses declared by the major banks as of the end of last year came to around $100 billion, roughly 40-50% of the estimated latent loss. (Figure 3)

Update, 2008-3-25: Goldman Sachs is estimating $460-billion to the “leveraged sector”:

Wall Street banks, brokerages and hedge funds may report $460 billion in credit losses from the collapse of the subprime mortgage market, or almost four times the amount already disclosed, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Profits will continue to wane, other analysts said.

“There is light at the end of the tunnel, but it is still rather dim,” Goldman analysts including New York-based Andrew Tilton said in a note to investors today. They estimated that residential mortgage losses will account for half the total, and commercial mortgages as much as 20 percent.

Note that Goldman Sachs influenced the conclusions of the paper reviewed in this post, so this is not a fully independent estimate.