These are some notes for a forthcoming article.

The US Interagency Policy Statement on the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (via Deloitte’s IAS Plus, December 16, 2006.

FAS 5 requires the accrual of a loss contingency when information available prior to the issuance of the financial statements indicates it is probable that an asset has been impaired at the date of the financial statements and the amount of loss can be reasonably estimated. These conditions may be considered in relation to individual loans or in relation to groups of similar types of loans. If the conditions are met, accrual should be made even though the particular loans that are uncollectible may not be identifiable. Under FAS 114, an individual loan is impaired when, based on current information and events, it is probable that a creditor will be unable to collect all amounts due according to the contractual terms of the loan agreement. It is implicit in these conditions that it must be probable that one or more future events will occur confirming the fact of the loss. Thus, under GAAP, the purpose of the ALLL is not to absorb all of the risk in the loan portfolio, but to cover probable credit losses that have already been incurred.

…

Typically, institutions evaluate and estimate credit losses for off-balance sheet credit exposures at the same time that they estimate credit losses for loans. While a similar process should be followed to support loss estimates related to off-balance sheet exposures, these estimated credit losses are not recorded as part of the ALLL. When the conditions for accrual of a loss under FAS 5 are met, an institution should maintain and report as a separate liability account, an allowance that is appropriate to cover estimated credit losses on off-balance sheet loan commitments, standby letters of credit, and guarantees.

The discussion in Donald Powell’s testimony to the Senate Banking, Housing & Urban Affairs Committee (2005) states:

Some comment is also needed about the possibility of using the allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL) as a benchmark for evaluating the conservatism of ELs. The aggregate allowance reported by the 26 companies in QIS-4 totaled about $55 billion, and exceeded their aggregate EL, and this comparison might suggest the ELs were not particularly conservative and could be expected to increase. We do not believe this would be a valid inference. The ALLL is determined based on a methodology that measures losses imbedded over a non-specific future time horizon. Basel II ELs, in contrast, are intended to represent expected one-year credit losses. Basel II in effect requires the allowance to exceed the EL (otherwise there is a dollar for dollar capital deduction to make up for any shortfall). More important, the Basel II framework contains no suggestion that if the EL is less than the ALLL, then the EL needs to be increased—on the contrary this situation is encouraged, up to a limit, with tier 2 capital credit.

Given these considerations, we regard the comparison of ELs to average charge offs as a proxy for the degree of conservatism imbedded in PD and LGD estimates. ELs that are in excess of loss experience in effect imbed a cushion into QIS-4 capital requirement, and suggest that when the system goes live, lower capital requirements could be supported consistent with the standards prescribed by the framework.

A defense of Future Margin Income as an offset to EL – Future Margin Income and the EL Charge for Credit Cards in Basel II:

Specifically, while regulators view the ALLL as serving the purpose of “covering” EL, practitioners disagree and say that loan yields must at least cover EL so that all of the ALLL is available to serve a capital purpose. Specifically, practitioners say that yields must be at least enough to cover interest expenses, all net noninterest expenses, all expected credit losses, and a market return to economic capital. If this is not the case, the bank has

priced the loan too low and the loan is not generating any added value to the bank’s shareholders.

Risk Management Association comment letter (2003)

Basel staff apparently believes that, since Total Capital is defined to include the ALLL, and since some supervisors and some bankers have stated that “the ALLL covers EL”, required Total Capital should therefore be measured as LCI inclusive of EL, not net of EL.

This supervisory view is in sharp contrast to the view of the risk practitioner. In our view, the ALLL is an accounting item that has nothing to do with covering EL and, in fact, has nothing to do with measuring required risk-adjusted or economic capital. There is a quite separate question, of course, as to whether the ALLL should be among those balance sheet items that constitute actual capital for purposes of deciding whether such balance sheet capital is at least as high as measured Economic Capital (EC). If such a balance sheet test is not met that is, if the bank’s balance sheet analogue to mark-to-market capital (mark to market net asset value) is not at least equal to EC then the bank is undercapitalized by its own standards. The bank cannot be meeting its particular debt-rating target (soundness target) unless it has real capital at least equal to measured EC. Until Basel’s authors separate these two issues a) how to measure required capital (EC) versus b) how to define the balance sheet items that should be included within a measurement of actual capital it will continue to have difficulty aligning the Pillar 1 requirements with best-practice economic capital procedures. In the market’s view, capital is not needed to cover EL because the essential risk pricing and shareholder value-added relationships require that EL be at least covered by expected future margins. Note that we do not say that EL is covered by actual future margins, only that expected losses are at least covered by expected margins. Business practice has always required that prices cover expected losses, other expenses, and a return to capital even before the advent of Economic Capital.

…

Not only should required capital be measured net of EL, but also, as indicated above, actual mark-to-market capital is best approximated by including the ALLL in Tier 1 capital. It is Tier 1 capital that is the true, expensive form of capital, and including the ALLL in Tier 1 would reduce, if not eliminate, inequitable capital treatment across nations associated with differences in the accounting treatment of the ALLL. That is, abstracting from tax and dividend effects, any mandated high levels of ALLL (in a conservative ALLL country) would correspondingly reduce retained earnings, while any leniency in accounting for ALLL (in liberal ALLL countries) would result in increased retained earnings.

Competitive Effects of Basel II on US Bank Credit Card Lending (2007)

We analyze the potential competitive effects of the proposed Basel II capital regulations on U.S. bank credit card lending. We find that bank issuers operating under Basel II will face higher regulatory capital minimums than Basel I banks, with differences due to the way the two regulations treat reserves and gain-on-sale of securitized assets. During periods of normal economic conditions, this is not likely to have a competitive effect; however, during periods of substantial stress in credit card portfolios, Basel II banks could face a significant competitive disadvantage relative to Basel I banks and nonbank issuers.

…

There are several important differences between the Basel II rules and Basel I rules with respect to the measurement of regulatory capital. The Basel II regime defines capital as a cushion against unexpected losses and not against all losses as in Basel I. Thus, under Basel II, expected losses (calculated as PD × EAD × LGD) are deducted from total capital. This change in the concept of capital is particularly important for credit cards, since expected losses on credit cards are approximately 10 times higher than those on other bank loan products. Thus, a large component of the impact of Basel II on effective capital requirements comes from the deduction of expected loss from total regulatory capital and the treatment of the allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL), which is meant to offset the bank’s expected losses.

…

The ALLL and expected losses also affect the definition of tier 1 capital under Basel II but not under Basel I. If eligible reserves are less than expected losses, then half of the reserve shortfall is deducted from tier 1 capital. This shortfall is calculated based on a bank’s entire portfolio and not product by product. Whereas bank reserves allocated to credit card loans are typically less than expected losses, reserves often exceed expected losses for many other bank products. Thus, Basel II monoline credit card banks would typically have a substantial tier 1 capital deduction due to the reserve shortfall, while most diversified banking institutions would not have a tier 1 deduction, since the surplus reserves in other portfolios will offset the reserve shortfall in the credit card portfolio. Thus, under Basel II, monolines benefit with respect to total capital because of the reserve cap provision but issuers within diversified banking organizations benefit with respect to tier 1 capital because of the treatment of the reserve shortfall.

Risk Management Assoc., 2004:

The Framework’s limit on the amount of the ALLL that can count as Tier 2 capital. In the U.S. (and possibly in some other Basel countries), single-family residential (“SFR”) lending and credit card lending could be handicapped by the Framework’s treatment of the [ALLL minus EL] test. Reserves for SFRs, as is the case for other business lines, are accounted for roughly in proportion to current expected loss rates on the SFR portfolio. Over the last several years, even with the recent recession, such expected loss rates have been low. As a result, mortgage businesses have tended to hold their economic capital in the form of real equity, not in the form of high reserves. Basel LGDs, however, would likely be a multiple of current economic LGDs, which, under the Framework, could lead to a “shortfall” in the ALLL minus EL calculation. Fifty percent of this shortfall must be deducted from Tier 1 capital and 50% from Tier 2 capital, for regulatory capital purposes. Even though the market views the sum of Tier 1 plus the ALLL to be a cushion against unexpected losses, the mortgage business lines would be penalized for holding their capital in the form of equity rather than reserves.

In credit card lending, accounting practices also do not permit high reserves. footnote 3 In particular, U.S. banks are not permitted to establish a loan loss reserve for the undrawn portion of lines. Moreover, some banks do not reserve for accounts held for securitization (which are carried at fair value or LOCOM). Most importantly, auditors may require that the ALLL for outstanding card balances be computed over a shorter horizon than the one-year horizon associated with EL. As a consequence, [ALLL – EL] may be in a shortfall for banks engaged in the card business — especially, for those banks securitizing some portion of their card accounts. Banks that engage in the card business therefore may hold capital in the form of equity, not reserves, against the risk of such products — and the market does not distinguish between these two forms of capital. Similar problems may arise within other retail lines of business such as HELOCs and home equity term loans.

We suggest that the inequities associated with the [ALLL-EL] test may be alleviated through country-specific treatment of the ALLL-EL computation. That is, where GAAP does not permit there to be a positive ALLL-EL computation, the supervisor might first make a determination as to the sufficiency of overall bank capital. Where no capital deficiency exists, the supervisor could then treat the ALLL for capital purposes as if it equaled EL. Still another method to treat the problem would be for supervisors to permit an EL calculation (only for purposes of the ALLL-EL test) in which the EL calculation uses the same horizon and assumptions as are built into the accounting treatment of the ALLL.

Note: footnote 3 Although accounting practices do not permit high reserves, the bank still has a market capital requirement that must be met with another form of equity. Thus, the ratios of Tier 1 to Total Capital at the large mortgage and card specialists in the RMA group are significantly higher than for large full-line banks. It would be inequitable to reduce the amount of recognized Tier 1 at these institutions because of accounting procedures.

footnote 4 There are at least three types of differences in assumptions that exist between the GAAP treatment of provisions and the EL computation as required by Basel: a) GAAP may require a shorter time horizon; b) GAAP may not include all of the economic expenses associated with default and recovery, such as certain foreclosure and REO expenses, and the time value of money; and c) GAAP provisioning incorporates current expectations regarding LGDs, not stressed LGDs.

Repullo & Suarez examined the procyclicity of Basel II and estimated:

Under realistic parameterisations, Basel II leads banks to hold buffers that range from about 2% of assets in recessions to about 5% in expansions. The procyclicality of these buffers reflects the fact that banks are concerned about the upsurge in capital requirements that takes place when the economy goes into a recession. We find, however, that these equilibrium buffers are insufficient to neutralise the effects of the arrival of a recession, which may cause a very significant reduction in the supply of credit – ranging from 2.5% to 12% in our simulations, depending on the assumed cyclical variation of the default rates.

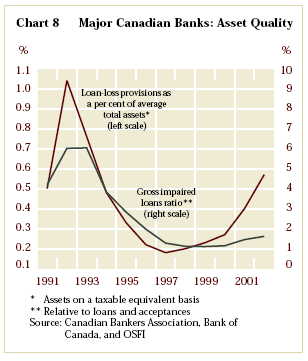

Bank of Canada Financial System Review, June 2003:

Update, 2008-07-23: See also What Constrains Banks?

Update, 2008-07-23: Basel II and the Scope for Prompt Corrective Action in Europe:

The Quantitative Impact Studies conducted by the Basel Committee regarding the effects of implementing the Internal Ratings standard indicate that many banks will be able to lower their required capital as much as 25 percent while other similar banks will not be able to reduce their required capital at all. The variation in capital requirements across banks that seem to be similar in terms of risk-taking can become very large. This sensitivity of banks’ required capital to their choice of assets could lead to distortions of banks’ investments in risky assets. Banks will favour some assets over others in spite of similar risk and return because they can reduce the required capital without reducing the return on assets. One remedy for such distortions is to use PCA trigger ratios to introduce definitions that do not depend on Basel II risk weights. One possibility is to use simple leverage ratios (equity to non-weighted assets) as trigger ratios. Another is to use the standardized risk-weights in Basel II based on evaluations of borrowers by external rating agencies.

See also Bank Regulation: The Assets to Capital Multiple.

WaMu Letter, 2004:

As a final point, the U.S. applies an even more arbitrary “Tier 1 leverage” ratio of 5% (defined as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to total assets) in order for a bank to be deemed “well-capitalized”. As we have noted in our prior responses, the leverage requirement forces banks with the least risky portfolios (those for which best-practice Economic Capital requirements and Basel minimum Tier 1 requirements are less than 5% of un-risk-weighted assets) either to engage in costly securitization to reduce reported asset levels or give up their lowest risk business lines. These perverse effects were not envisioned by the authors of the U.S. “well-capitalized” rules, but some other Basel countries have adopted these rules and still others might be contemplating doing the same.

…

ALLL should continue to be included in a bank’s actual capital irrespective of EL. As we and other sources [footnotes] have noted, it is our profit margins net the cost of holding (economic) capital that must more than cover EL. As a member of the Risk Management Association’s (RMA) Capital Working Group, we refer the reader to a previously published detailed discussion of this issue that we have participated with other RMA members in developingfootnote 4. This issue is also addressed at length in RMA’s pending response to this same Oct. 11, 2003 proposal.

A Bridge too Far, Peter J. Wallison, 2006

Furthermore, the Basel formulas do not take into account a bank’s portfolio as a whole; they operate solely by adding up the assessments of each individual exposure and thus do not consider concentration risk.

…

[Footnote] The BCBS notes: “The model should be portfolio invariant, i.e. the capital required for any given loan should only depend on the risk of that loan and must not depend on the portfolio it is added to. This characteristic has been deemed vital in order to make the new IRB framework applicable to a wider range of countries and institutions. Taking into account the actual portfolio composition when determining capital for each loan — as is done in more advanced credit portfolio models — would have been a too complex task for most banks and supervisors alike.” (BCBS, An Explanatory Note, 4.)

…

To compensate for Basel II’s deficiencies, U.S. regulators (under Congressional pressure) have decided to keep the leverage ratio as an element of the capital tests that would be applied to banks even if Basel II is ultimately adopted. This seems sensible. The leverage ratio — tier 1 capital divided by total assets — is not a formula, nor is it risk-based; it is simply a measurement of the size of the ultimate capital cushion that a bank has available in the event of severe losses. It is an important fail-safe measure because it will become the binding element of the capital requirements for banks using Basel II if their risk-based capital levels — as measured by the IRB approach — fall too low. In a sense, no harm can come from the deficiencies of Basel II as long as the leverage ratio — at its current level — remains in place.

Heavyweights clash over “meaningless” ratios :

But the FDIC is the first to explicitly identify a possible conflict between this existing US approach to bank safety and possible outcomes under Basel II – and to marshal a strong defence of the leverage ratio.

…

This is because bank capital is divided into Tier 1 and Tier 2 categories. Yet, only Tier 1 capital really counts, because that is real equity. Tier 2 capital consists of subordinated debt. An increase in subordinated debt does not decrease a bank’s probability of insolvency. In fact, it is the failure of that debt that constitutes insolvency, says [independent consultant, and advisor to the Philadelphia-based Risk Management Association (RMA), John] Mingo.

So, it is only Tier 1 capital that determines insolvency probability. “The Basel Committee, being political, was obliged to adopt total capital as its standard – including subordinated debt – because the Japanese banks don’t have any equity,” he adds. The decision to make Tier 1 capital a minimum of half total capital, as well as the choice of a 99.9% confidence interval for total capital, were also arbitrary, in Mingo’s view.

Everything Old is New Again – The Return of the Leverage Ratio:

On June 19, 2008, Peter Thal Larsen of the Financial Times reported that, “Philipp Hildebrand, vice-chairman of the Swiss National Bank, called for the introduction of a “leverage ratio”, which would place a limit on the extent to which a bank’s assets could exceed its capital base.” (“Swiss banker calls for ‘leverage ratio’”, Peter Thal Larsen, June 19 2008) The idea now is that while adjusting the leverage ratio for risk is a laudable goal, the models that facilitate the adjustment are necessarily flawed to one extent or another and cannot be adequately relied upon, in isolation.

Good background piece: The Basel Accords: The Implementation of II and the Modification of I – Congressional Research Service, 2006

IIF, ISDA, LIBA comment letter, 2007:

The Agencies have publicly indicated their intention to retain the leverage ratio in conjunction with the new international framework capital requirements. We believe that the leverage ratio should be reviewed for phase-out upon completion of the introduction of the international framework. This device not only lacks risk sensitivity but ignores fundamental principles by which modern financial institutions manage their portfolios and risks. In particular, the application of the leverage ratio is inconsistent with the fundamental Basel II principle by which banks can improve their risk profiles either by holding additional capital or by holding less risk in their portfolios. In essence, a regulatory capital tool that limits itself to a crude comparison of assets in the balance sheet against capital is inconsistent with the way financial institutions currently operate.

For certain banks subject to the international framework, the leverage ratio will become a binding constraint because of its lack of risk sensitivity. Banks that accumulate low credit risk assets on their balance sheets will be penalized for adopting such a strategy, because the leverage ratio is not dependent on how conservatively banks operate. This will have the counter-prudential effect of encouraging those banks that find themselves constrained by the leverage ratio to change strategy, possibly by acquiring riskier assets until their regulatory risk-based capital and leverage capital requirements are equalized, or by reducing their willingness to provide credit services vital to the health of the economy.

Even banks that have very strong capital structures, with substantial Tier 1 capital against RWA, may be caught by the rigidity of the leverage ratio. The leverage ratio requirement thus can distort market perceptions and improperly interfere with management strategy, because it is a constraint inconsistent with the objective of introducing more risk-sensitive capital requirements, as agreed through the international framework. Continuation of the leverage ratio undermines many of the purposes the regulatory community – including the US regulators – sought to accomplish when they saw the need to replace Basel I.

Moreover, to the extent that the leverage ratio results in a higher minimum capital requirement than justified by the risk presented by banks’ activities, the regulatory requirement will have the effect of reducing the flow of credit to the economy. We therefore believe that the permanent retention of the leverage ratio is not appropriate from an economic perspective. It may be unavoidable to retain a leverage ratio during the capital-floor periods to manage the transition from Basel I to Basel II, but this should be a temporary expedient, subject to regulatory review within a reasonable period of time. It should be stressed that this is a comment on the lack of risk sensitivity, risk-management disincentives, and negative international competitive effects of the leverage ratio. It is not a comment on the general concept of prompt corrective action (PCA). We support the principle of prompt corrective action properly linked with the more appropriate risk-sensitive requirements of Basel II, which in turn will strengthen PCA’s effectiveness.

Update, 2008-7-24: See also