The Boston Fed has released a paper titled Making Sense of the SubPrime Crisis by Kristopher S. Gerardi, Andreas Lehnert, Shane M. Sherland, and Paul S. Willen with the abstract:

This paper explores the question of whether market participants could have or should have anticipated the large increase in foreclosures that occurred in 2007 and 2008. Most of these foreclosures stem from loans originated in 2005 and 2006, leading many to suspect that lenders originated a large volume of extremely risky loans during this period. However, the authors show that while loans originated in this period did carry extra risk factors, particularly increased leverage, underwriting standards alone cannot explain the dramatic rise in foreclosures. Focusing on the role of house prices, the authors ask whether market participants underestimated the likelihood of a fall in house prices or the sensitivity of foreclosures to house prices. The authors show that, given available data, market participants should have been able to understand that a significant fall in prices would cause a large increase in foreclosures, although loan‐level (as opposed to ownership‐level) models would have predicted a smaller rise than actually occurred. Examining analyst reports and other contemporary discussions of the mortgage market to see what market participants thought would happen, the authors find that analysts, on the whole, understood that a fall in prices would have disastrous consequences for the market but assigned a low probability to such an outcome.

As an illustration of the risks inherent in estimating tail risk – or even defining which is the tail and which is the belly, there are so many people claiming it was always obvious – they cite:

As an illustrative example, consider a 2005 analyst report published by a large investment bank: it analyzed a representative deal composed of 2005 vintage loans and argued it would face 17 percent cumulative losses in a “meltdown” scenario in which house prices fell 5 percent over the life of the deal. Their analysis is prescient: the ABX index (an index that represents a basket of credit default swaps on high-risk mortgages and home equity loans) currently implies that such a deal will actually face losses of 18.3 percent over its life. The problem was that the report only assigned a 5 percent probability to the meltdown scenario, whereas it assigned a 15 percent probability and a 50 percent probability to scenarios in which house prices grew 11 percent and 5 percent, respectively, over the life of the deal.

With regard to the obviousness of the housing bubble, they point out:

Broadly speaking, we maintain the assumption that while, in the aggregate, lending standards may indeed have affected house price dynamics (we are agnostic on this point), no individual market participant felt that he could affect prices with his actions. Nor do we analyze whether the housing market was overvalued in 2005 and 2006, and whether a collapse of house prices was

therefore, to some extent, predictable. There was a lively debate during that period, with some arguing that housing was reasonably valued (see Himmelberg, Mayer, and Sinai 2005 and McCarthy and Peach 2004) and others arguing that it was overvalued (see Gallin 2006, Gallin 2008, and Davis, Lehnert, and Martin 2008).

The Fed’s researchers are not impressed by the current demonization of the “originate and distribute” model:

Many have argued that a major driver of the subprime crisis was the increased use of securitization. In this view, the “originate to distribute” business model of many mortgage finance companies separated the underwriter making the credit extension decision from exposure to the ultimate credit quality of the borrower and thus created an incentive to maximize lending volume without concern for default rates. In addition, information asymmetries, unfamiliarity with the market, or other factors prevented investors who were buying the credit risk fromputting in place effective controls for these incentives. While this argument is intuitively persuasive, our results are not consistent with such an explanation. One of our key findings is that most of the uncertainty about losses stemmed from uncertainty about the evolution of house prices and not from uncertainty about the quality of the underwriting. All that said, our models do not perfectly predict the defaults that occurred, and these often underestimate the number of defaults. One possible explanation is that there was an unobservable deterioration of underwriting standards in 2005 and 2006. But another possible explanation is that our model of the highly non-linear relationship between prices and foreclosures is wanting. No existing research successfully separates the two explanations.

Resets? Schmresets!

No discussion of the subprime crisis of 2007 and 2008 is complete without mention of the interest rate resets built into many subprime mortgages that virtually guaranteed large payment increases. Many commentators have attributed the crisis to the payment shock associated with the first reset of subprime 2/28 mortgages. However, the evidence from loan-level data shows that resets cannot account for a significant portion of the increase in foreclosures. Both Mayer, Pence, and Sherlund (2008) and Foote, Gerardi, Goette, and Willen (2007) show that the overwhelming majority of defaults on subprime adjustable-rate mortgages (ARM) occur long before the first reset. In other words, many lenders would have been lucky had borrowers waited until the first reset to default.

One interesting and doomed to be unrecognized factor is:

Investors allocated appreciable fractions of their portfolios to the subprime market because, in one key sense, it was considered less risky than the prime market. The issue was prepayments, and the evidence showed that subprime borrowers prepaid much less efficiently than prime borrowers, meaning that they did not immediately exploit advantageous changes in interest rates to refinance into lower rate loans. Thus, the sensitivity of the income stream from a pool of subprime loans to interest rate changes was lower than the sensitivity of a pool of prime mortgages.

…

Mortgage pricing revolved around the sensitivity of refinancing to interest rates; subprime loans appeared to be a useful class of assets whose cash flow was not particularly correlated with interest rate shocks.

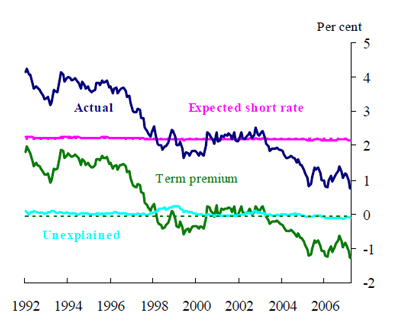

Risks may be represented as:

if we let f represent foreclosures, p represent prices, and t represent time, then we can decompose the growth in foreclosures over time, df/dt, into a part corresponding to the change in prices over time and a part reflecting the sensitivity of foreclosures to prices:

df/dt = df/dp × dp/dt.

Our goal is to determine whether market participants underestimated df/dp, the sensitivity of foreclosures to prices, or whether dp/dt, the trajectory of house prices, came out much worse than they expected.

And how about those blasted Credit Rating Agencies (they work for the issuers, you know):

As a rating agency, S&P was forced to focus on the worst possible scenario rather than the most likely one. And their worst-case scenario is remarkably close to what actually happened. In September of 2005, they considered the following:

- a 30 percent house price decline over two years for 50 percent of the pool

- a 10 percent house price decline over two years for 50 percent of the pool.

- an economy that was“slowing but not recessionary”

- a cut in Fed Funds rate to 2.75 percent

- a strong recovery in 2008.

In this scenario, they concluded that cumulative losses would be 5.82 percent.

…

Their problem was in forecasting the major losses that would occur later. As a Bank C analyst recently said, “The steepest part of the loss ramp lies straight ahead.” S&P concluded that none of the investment grade tranches of RMBSs would be affected at all — that is, no defaults or downgrades would occur. In May of 2006, they updated their scenario to include a minor recession in 2007, and they eliminated both the rate cut and the strong recovery. They still saw no downgrades of any A-rated bonds or most of the BBB-rated bonds. They did expect widespread defaults, but this was, after all, a scenario they considered “highly unlikely.” Although S&P does not provide detailed information on their model of credit losses, it is impossible to avoid concluding that their estimates of df/dp were way off. They obviously appreciated that df/dp was not zero, but their estimates were clearly too small.

As I’ve stressed whenever discussing the role of Credit Rating Agencies, their rating represent advice and opinion (necessarily, since it involves predictions of the future); the receipt of credit reports is not limited to the peak of Mount Sinai. Some disputed this advice:

The problems with the S&P analysis did not go unnoticed. Bank A analysts disagreed sharply with S&P:

Our loss projections in the S&P scenario are vastly different from S&P’s projections with the same scenario. For 2005 subprime loans, S&P predicts lifetime cumulative losses of 5.8 percent, which is less than half our number… We believe that S&P numbers greatly understate the risk of HPA declines.

The irony of this is that both S&P and Bank A ended up quite bullish, but for different reasons. S&P apparently believed that df/dp was low, whereas most analysts appear to have believed that dp/dt was unlikely to fall substantially.

And other forecasts were equally unlucky:

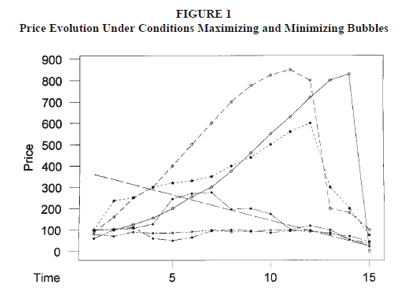

Bank B analysts actually assigned probabilities to various house price outcomes. They considered five scenarios:

| Name |

Scenario |

Probability |

| (1) Aggressive |

11% HPA over the life of the pool |

15% |

| (2) [No name] |

8% HPA over the life of the pool |

15% |

| (3) Base |

HPA slows to 5% by year-end 2005 |

50% |

| (4) Pessimistic |

0% HPA for the next 3 years, 5% thereafter |

15% |

| (5) Meltdown |

-5% for the next 3 years, 5% thereafter |

5% |

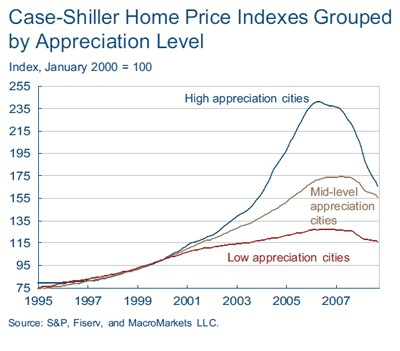

Over the relevant period, HPA actually came in a little below the -5 percent of the meltdown scenario, according to the Case-Shiller index. Reinforcing the idea that they viewed the meltdown as implausible, the analysts devoted no time to discussing the consequences of the meltdown scenario even though it is clear from tables in the paper that it would lead to widespread defaults and downgrades, even among the highly rated investment grade subprime ABS.

The authors conclude:

In the end, one has to wonder whether market participants underestimated the probability of a house price collapse or misunderstood the consequences of such a collapse. Thus, in Section 4, we describe our reading of the mountain of research reports, media commentary, and other written records left by market participants of the era. Investors were focused on issues such as small differences in prepayment speeds that, in hindsight, appear of secondary importance to the credit losses stemming from a house price

downturn. When they did consider scenarios with house price declines, market participants as a whole appear to have correctly identified the subsequent losses. However, such scenarios were labeled as “meltdowns” and ascribed very low probabilities. At the time, there was a lively debate over the future course of house prices, with disagreement over valuation metrics and even the correct index with which to measure house prices. Thus, at the start of 2005, it was genuinely possible to be convinced that nominal U.S. house prices would not fall substantially.

This is a really superb paper; so good that it will be ignored in the coming regulatory debate. The impetus to tell the story that people want to hear hasn’t changed – only the details of the story.

PrefBlog’s Assiduous Readers, however, will file this one under “Forecasting”, with a copy to “Tail Risk”.