Robert McDonald of Northwestern University has published a paper titled Contingent Capital with a Dual Price Trigger that I consider excellent – mainly because it advocates a framework for Contingent Capital that includes the structure I advocate (and have been advocating ever since HM Treasury’s Turner Report response brought the basic idea to my attention) and supports it with rationale that reflects my biases.

This paper proposes a form of contingent capital for financial institutions that converts from debt to equity if two conditions are met: the firm’s stock price is at or below a trigger value and the value of a financial institutions index is also at or below a trigger value. This structure protects financial firms during a crisis, when all are performing badly, but during normal times permits a bank performing badly to go bankrupt. I discuss a number of issues associated with the design of a contingent capital claim, including susceptibility to manipulation and whether conversion should be for a fixed dollar amount of shares or a fixed number of shares; the susceptibility of different contingent capital schemes to different kinds of errors (under and over-capitalization); and the losses likely to be incurred by shareholders upon the imposition of a requirement for contingent capital. I also present some illustrative pricing examples.

His specific proposal is:

The contingent capital claim that I describe, “dual trigger contingent capital”, converts automatically based on market prices, without reference to accounting-based measures of capital. Specifically, it converts to equity when the bank’s own stock price falls sufficiently, and then only if a broad �nancial stock index is also below a trigger value. (This condition can be eliminated by making the trigger sufficiently large.) This structure reduces the debt load for poorly-performing institutions in times of crisis, but permits individual banks to fail in good times.

The major benefits of using market prices are:

Simplicity and transparency should facilitate market acceptance and reduce the (appropriately-measured) cost to banks of issuing convertible claims. The use of market-based triggers, with no reliance on accounting numbers, means that conversion is unaffected by accounting rule reinterpretations or changes. Making conversion automatic and based only on market prices should reduce pressure on regulators and the accounting community at critical times. Also, private information of either the firm or the regulator has no bearing on the conversion decision.

My point that using market prices and fixed conversion rates will facilitate the hedging of CC in the options market – and therefore the liquidity in a crisis – may be considered included in the “facilitate market acceptance” phrase.

I did not address one point he considers critical (which was further discussed, albeit in a highly unsatisfactory manner, by FRBNY staff) is:

A critical issue is the precise manner in which conversion occurs, and the possibility of stock price manipulation. In Section 3 I discuss a number of design considerations and I conclude that conversion of the bond into a fixed number of shares at a premium price minimizes concerns about manipulation.(footnote) The tradeo� is that such a structure raises the yield on convertible debt. (This greater yield is of course fair compensation for the loss imposed upon bondholders should conversion occur.)

footnote: “Premium price” here means that the value of the shares upon conversion is lower than the par value of the bonds. In e�ect, the bondholder is paying a greater than market price for the shares received. I dicuss this more in Section 1.

So consider a pref issued at $25 when the common is at $50. In the base proposal, if the common falls below $25 (for a defined period), the pref will convert at par into the trigger price; preferred shareholders will receive one common for each pref. With “premium pricing”, preferred shareholders will received less than one share, while the trigger price remains the same. I’ll discuss this later.

Also, note that I am (for obvious reasons) focussing on preferred shares while all the academic discussion I have seen focusses on sub-debt. I think that should CC effectively replace sub-debt, then similar conversion features will be applied to prefs – otherwise, preferreds will be effectively senior to CC (in that they will retain their claims when everything else is converted, and remain senior when the bank goes bust) and I don’t think the markets will stand for such leapfrogging.

His example provides the rationale behind an expected yield spread over senior debt:

To more fully understand the events at conversion, suppose that at some time after issue the �nancial index is below 90 and the stock price reaches $50. At this point bondholders are entitled to 20 shares. Typically, however, the stock price will not close exactly at $50, but say at $48. In this case the bondholders receive shares worth 20 � $48 = $960. Thus, conversion on average will leave the bondholders slightly worse o� than if the bond paid par value. As a result, the market will demand a slightly higher interest rate on the bond than if it were sure to convert into $50 worth of shares.(footnote)

footnote: An alternative would be to adjust the number of shares to make their value equal to the par value of the bond. As I discuss in Section 3, this alternative conversion scheme increases the returns to stock price manipulation.

In other words, the option effect. I should note that there will also be a spread required due to uncertainty – typically, bond holders will not have a mandate or desire to hold equity; hence, it is likely that the embedded short option will be overvalued.

He notes:

This structure accomplishes several things:

- The conversion of bonds to shares occurs only if there is a widespread fall in the value of financial firm shares. One would expect such a widespread fall during a �nancial crisis, not at other times.

- A dual trigger convertible permits the failure of an institution as long as the �nancial industry as a whole is peforming well. Without a fall in the index, bonds would not convert and the financial institution could go bankrupt. The note can be structured to avoid this.

- There would be no regulatory involvement in the conversion decision

- Conversion would not depend upon acccounting rules or the institution’s reported capital. If the market believed that a bank’s assets were worth less than the bank reported, conversion would occur if the share price and index conditions were satisifed.

- The proposal is not subject to equity death spirals: In the fixed share structure, the number of shares exchanged for bonds would be fixed.

These are eminently sensible reasons. However, I remain dubious about the inclusion of the second, industry-wide trigger. Firstly, it will depend upon the composition of third-party indices, which can be – and often are – manipulated. Secondly, it will complicate pricing of the CC, which will mean that not all of the mathematical benefits of the reduced conversion chance will be realized.

Additionally, his footnote to the second point states:

If an institution is too-big-to-fail, the use of an index trigger raises the possibility of multiple equilibria. Consider a circumstance where a) the financial index would fall below the trigger if and only if the too-big-to-fail institution were to fail and b) conversion of the contingent capital would prevent failure. If the contingent capital were expected to convert and prevent failure, the index would never fall below the trigger value and thus the contingent capital would not convert. If the contingent capital were expected not to convert, the index would fall below the trigger value and the capital would convert. While the requirements seem empirically unlikely, it would be important to understand the equilibrium that would obtain in this case. I thank Zhenyu Wang for pointing out this issue.

He discusses the Flannery and Squam Lake proposals previously discussed on PrefBlog:

The Flannery and Squam Lake proposals differ in the nature of the trigger, but more importantly they differ in the severity of the event that will cause conversion. The Squam Lake proposal implicitly seems to view hybrid convertibles as a last-ditch measure: banks would have violated covenants and more importantly, regulators would have declared the existence of a crisis. Presumably one reason for using contingent capital would be to prevent a systemic crisis from occurring in the �rst place. Is it possible that the use of a regulatory trigger creates multiple equilibria? Could regulators declaring the existence of a crisis could induce or worsen a crisis? More generally, it seems possible that regulators worrying about maintaining con�dence in capital markets would would be reluctant to declare the existence of a crisis until it is too late.

I take the view that a regulatory declaration that a crisis existed would grossly exacerbate an already bad market situation. Additionally, prior uncertainty regarding a regulatory decision will depress the price of the CC, exacerbating the value transfer problem deplored by FRBNY staff.

McDonald discusses the potential for manipulation:

In the context of contingent capital, a concern is that unprofitable manipulation of the stock can become profitable when the trader also has a position in market-triggered contingent convertibles. This seems to be a legitimate concern. In this discussion we will suppose for the sake of argument that it is possible for traders to temporarily move the price (for example temporarily push it down), while maintaining the traditional academic skepticism that such trading in shares alone can be pro�table. Ultimately the possibility of extensive manipulation and its importance is an empirical question.

He gives an example of manipulation:

To see how manipulation could be profitable, suppose that the stock is $51, and a $1000 bond converts into 20 shares when the price goes below $50. A trader owning this bond could possibly manipulate the price down to $49. This forces conversion, and the bondholder now owns 20 shares. When the price returns to $51, the bondholder has a position worth $1020, and has induced a 2% gain on the convertible (from $1000 to $1020) by triggering conversion.

It should be noted that the profitability of this eneavor will be increased if the trader has actually just purchased the CC at $900. But my question is: Is this manipulation, or is it arbitrage? Additionally, the assumption that the price returns to $51 implicitly assumes that the value of the firm is $51 and that markets are sufficiently efficient to reflect this value – this is a precise estimate and shaky assumption at the best of times and it may be assumed that conversion will occur during a period of highly inefficient markets.

To my mind, the important question is not whether a trader might be able to make a few bucks with the strategy, but whether such a strategy has the potential to cascade, with the approach of imminent conversion of other instruments – another series of bonds converting at $48. I’m not really all that concerned about transitory manipulation, since that simply provides an opportunity for value investors to buy at an artificially low price; but there could be genuine public policy concerns if this artificially low price made it difficult, or even impossible, for the firm to issue new capital at rates that permitted it to operate as a going concern. The attack on CIT group which essentially locked it out of the bond market until bankruptcy was triggered comes to mind as a possible example; but I have a feeling that we don’t know the whole story on that one.

It should be noted that, to the extent that converted former noteholders elect to sell their shares at the market, the effect can be modelled as a stop-loss order; such orders have been suggested as a factor in the May 6 market bungee-jump even though the exchanges have built in some protection against the effect.

I can’t really get all that excited about the issue of market manipulation – the only people hurt will be the idiots who trade on momentum. I suggest that the potential for what is, effectively, a stop-loss cascade is more worthy of academic attention.

His prescription is premium conversion:

The difficulty of the manipulation just described can be increased by creating a wedge between the par value of the bond and the conversion value of the shares, i.e, the bond could convert at a premium price for the shares. For example, the bond could convert into 19 shares rather than 20. The bondholder who forced conversion would then receive a position worth $950 at the $50 trigger price, a loss of ($1000 – $950)/19 = $2:63/share generated by conversion. If the share price were $51 as in the previous example, the bondholder would lose $1.63/share by manipulating the price below $50. Temporary manipulation to a price below $50 would not become profitable until the true share price was at least $52.63. Hence, any manipulation would have to be by a greater amount to compensate for the premium price. Because conversion at a premium price would require a greater manipulation to make conversion profitable, manipulation would be both less likely and easier to detect. In fact, if shares convert at a premium, bondholders would have an incentive to manipulate the price up to avoid conversion. This seems likely to be more difficult than the downward manipulation just discussed, because the price has to be kept up indefinitely (or until the bond matures) to forestall conversion. If at any time the price falls, the bond converts. Also, propping up the price will be increasingly difficult to accomplish if the bank is in distress.

This is not entirely satisfactory, as it assumes the manipulator will be buying the bond at par, whereas in practice it is much more probable – virtually certain – that the manipulator will have purchased the bond well below par from a spooked investor who is taking a loss. For any premium, there will be some bond price that restores profitability, which may be thought of as providing a floor for the bond price. Thus, extant holders will be indirect and incomplete beneficiaries of the potential for manipulation.

He then notes that fixed-dollar conversion (conversion at market value) and is more susceptible to manipulation than fixed-share conversion.

He discusses instances in which CC does not act optimally in the context of Type I errors (conversion occurs when capital is not required) and Type II (conversion does not occur when capital is required):

In summary, market-based triggers seem prone to type I errors, and regulatory and accounting-based triggers seem prone to type II errors. It seems unlikely that there would be a systemic crisis without financial firms having low stock prices. This would reduce the likelihood of a type II error for market-based triggers. Accounting and regulation, however, are not automatic, and both are subject to political winds and whims. Basing conversion on regulatory judgment would reduce the likelihood of a type I error, in which bonds converted into stock without any crisis. But as discussed, one can imagine regulators failing to act. It is interesting to note that both the Flannery and Squam Lake proposals try not to saddle financial firms with “too much” equity. Flannery’s would convert only enough bonds to meet a capital requirement, and Squam Lake’s would convert only for banks with a low capital ratio.

To my immense gratification, he details problems with accounting-based conversion triggers:

- Most accounting is done periodically rather than continuously.

- Accounting rules are subject to political pressure.

- Accounting rules are subject to arbitrage.

- Accounting measures are often backward-looking

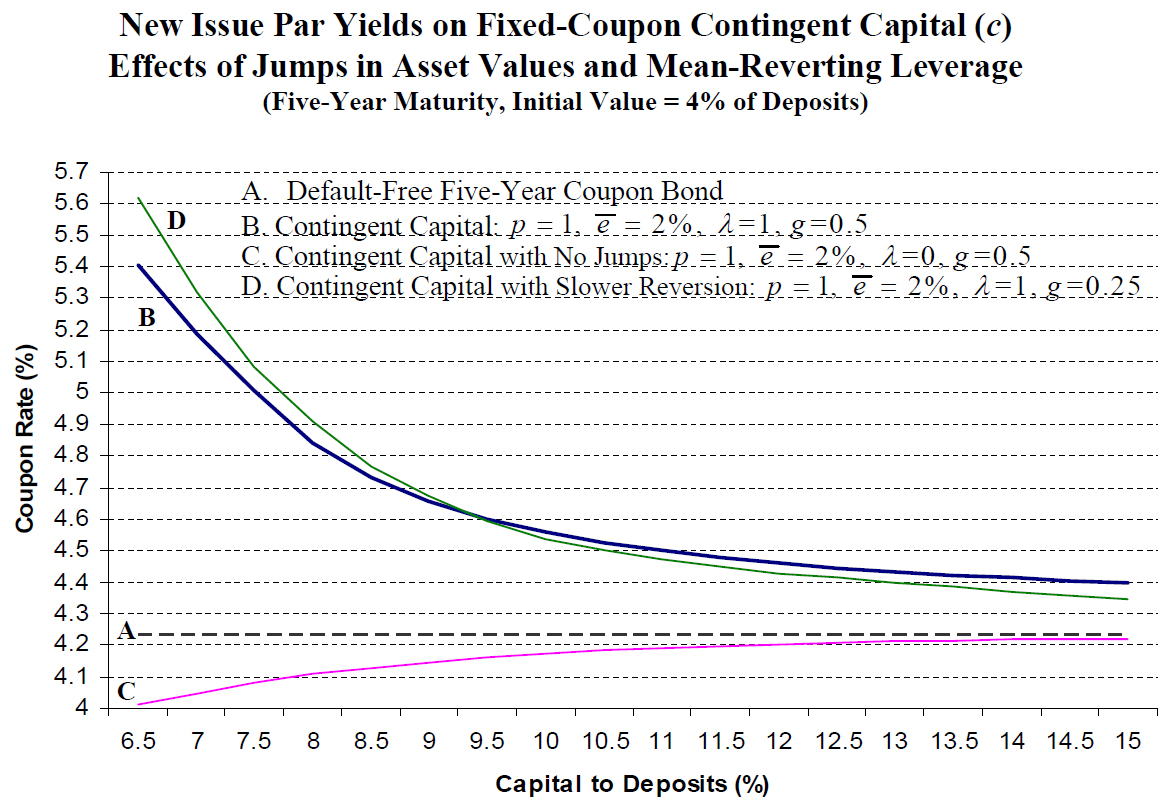

Of immense interest are his calculations regarding CC pricing:

In this section I perform some simple pricing exercises to illustrate characteristics of a dual-trigger contingent convertible under the assumption that both the stock price of the firm and the index are lognormally-distributed. Specifically, I assume that the stock price, St, and index price,Qt, both follow Ito processes, which is the standard assumption in the Black-Scholes model:

…

The correlation between dSt and dQt is ρ. Appendix A details the calculations. The stock price cannot reach zero in equation (1), so the yield calculation occurs in a context where bankruptcy is impossible. The yields I report therefore reflect only the effects of conversion.

Critical inputs into the pricing model are the volatility of the index, which I set to equal 20%, approximately the historical volatility of the Dow Jones Financial Services index from 1992 to 2007, and the stock volatility, which I set to 30%, approximately the historical volatility of banks like Citi, BofA, and Wells Fargo over this period. The correlation between the firm stock return and that of the index, again selected based on history, is 0.85.

…

Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the pricing of the convertible in a simple setting where

bankruptcy of the firm does not occur under any circumstances, but the convertible converts when the stock and index triggers are both satisifed. Pricing is by Monte Carlo. Specifically, I simulate the stock and index price, drawing new prices every day. The first time the stock and index prices are both below the trigger, the bond converts into a fixed number of shares. This simulation thus explictly models conversion occurring at a price below the trigger price, and thus generates a yield greater than the risk-free rate. The number in both tables is the annual yield premium above the risk-free rate.

…

Table 1 presents the bond yield premium when conversion occurs at the trigger price: If the bond has a par value of $1000 and the trigger price is $50, the bond converts into 20 shares. The maximum yield occurs when the stock trigger is relatively high (70% of the initial price) and the index trigger is low (80% of the initial index price). In this case it is relatively likely that the index trigger will not be satisifed when the stock reaches the trigger price, and thus on average conversion will occur when the stock is signi�cantly below the trigger price. The resulting premium is over 1%. Conversely, in the rightmost column the index trigger effectively does not exist. In this case the 25 basis point premium is entirely attributable to the bond converting below the trigger price. With a low stock trigger and a high index trigger, the bond premium is a negligible 2 basis points.

Table 2 examines the case where there is a 10% stock price premium at conversion.

| Table 1: Debt premium as a function of the index trigger and stock trigger. Assumes S0 = $100, Q0 = $100, σs = 0:30, σi = 0:20, ρ = 0:80, T = 5:00 years, h = 0:0040 (simulation timestep), r = 0:0400, with 50000 simulations. The conversion premium is 0.0000. |

| Note: I have converted the figures from the published table into basis points – JH |

| Stock Trigger |

Index Trigger |

| 80 |

100 |

120 |

140 |

1000 |

>

| 70 |

121 |

42 |

27 |

25 |

25 |

| 60 |

55 |

22 |

16 |

16 |

15 |

| 50 |

23 |

11 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

| 40 |

8 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| 30 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Thus, my original proposal is reflected in cell (1000, 50) of the table, and shows that there will be a yield premium of 9bp due to the conversion feature. Note, however, that this premium is a little bit of a cheat; losses are due only to the stock price over-shooting the conversion price, with the assumption that the shares are sold immediately.

Update, 2010-6-8: Prof. McDonald advises that: there is a certain amount of skepticism regarding the second, index-based, trigger; that there is concern regarding multiple equilibria if the conversion price is at a premium to the trigger price; that regulators consider the idea interesting but want more details and discussion; and that the potential for manipulation may increase the cost to issuers.

Update, 2010-6-10: I should note that the conversion trigger proposed by Prof. McDonald implies that a single trade of 100 shares can do the job. In my original proposal, I urged that the trigger be based on the common’s VWAP over a given period – say, 20 consecutive trading days. The latter format will make manipulation considerably more difficult, at the expense of potentially trapping CC noteholders in their investment if the common price declines precipituously over the VWAP measurement period.